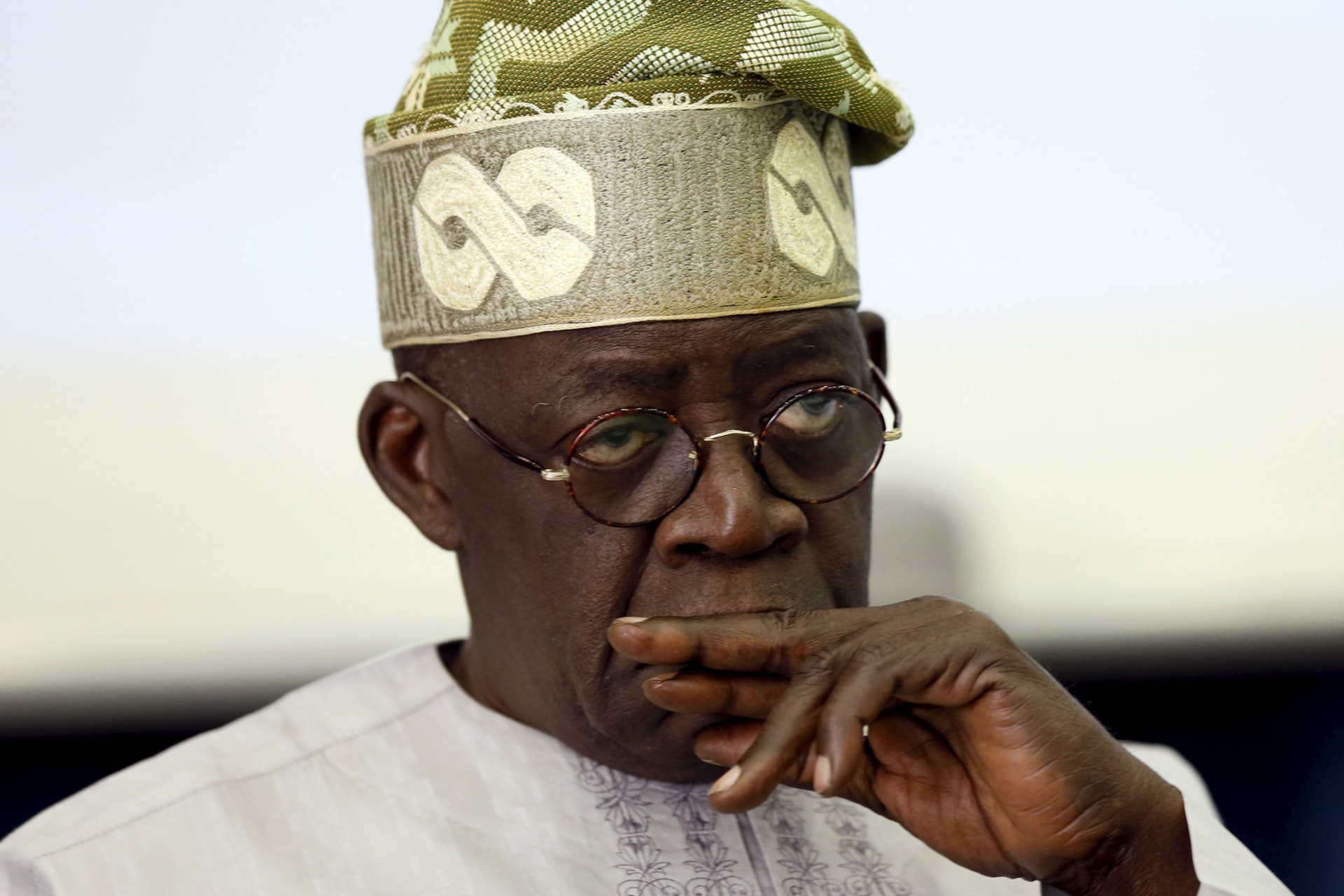

Tinubu’s Challenge

At a moment of deep generational fracture, the political opposition would seem to be the least of Bola Tinubu’s problems.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Ebenezer ObadareDouglas Dillon Senior Fellow for Africa Studies

By Ebenezer ObadareDouglas Dillon Senior Fellow for Africa Studies

For some time now, Bola Tinubu’s presidential ambition has been the worst kept secret in Nigerian politics. Although his name will technically be appearing on the ballot for the first time in next month’s general election, truth be told, Tinubu has been gunning for the country’s highest political office since he completed his two terms as Governor of Lagos State in 2007. In that regard, only Atiku Abubakar, the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) standard bearer, who has been involved in every presidential race since 1993, has been in the presidential race for much longer.

The comparison with Abubakar does not end there. Both have deep pockets, sit atop carefully curated and lubricated political networks, and realize that, realistically, this is their final throw of the dice. While, at seventy, Tinubu is six years younger than Abubakar, he must apprehend, given the inherent fickleness of political solidarity, that this is probably the last time that the stars will align in his favor. If there is a flavor of desperation in his campaign, this is its source. His body language and moves seem reminiscent of a veteran who knows he cannot afford to let the moment pass, hence the striking vigor of his insistence that “It is my turn” when, during the party primaries, he had every reason to believe he was on the verge of being schemed out. His every step since then suggests that he continues to believe that the forces that so nearly torpedoed him are merely in tactical abeyance.

Tinubu’s insolence towards President Muhammadu Buhari when he perceived that the latter was about to renege on a gentleman’s agreement on transfer of power confirmed that he is not unwilling to put everything on the line. His ultimate salvaging of victory from the jaws of apparent disaster was a reminder of his grit and ferocity, an attribute that one-time allies and clients who have crossed his path have often bitterly attested to.

Yet, if Tinubu has many enemies, likewise—and understandably for a politician who has been around the block—he has a train of loyalists across the country, ranging from office holders that he singlehandedly put on a pedestal, to random beneficiaries of his famed largesse. Patronage and politics are Siamese twins in (Nigerian) politics, and, with the possible exception of Abubakar, arguably no other Nigerian politician of his generation has spent more resources than Tinubu to lubricate the great machine of political patronage. Yet, not only, invariably, has Tinubu been unable to pacify every segment of the Nigerian society, but the source of his stupendous wealth is also a perennial bone of contention. For every Nigerian who insists that Tinubu’s wealth is ill-gotten, there is another one who counters that he merely typifies a political class that is rotten to the bone.

Tinubu and his aides have not answered nagging questions about the source of his wealth as much as parry them. Instead, they punt on the subject by focusing on what they boast are his outstanding achievements as Lagos State Governor (1999- 2007), and subsequently his role in ensuring that his successors, though handpicked stalwarts, are nonetheless savvy technocrats able to manage a bustling megalopolis. His electoral strategy has been consistent with this attitude; having more or less surrendered the digital space to its re-invigorated habitues, he has invested more time in cultivating the demographic that is, for want of a better word, under the radar, as well as powerful ethno-regional power brokers with the resources to mobilize broad based support.

The odds against this “traditional” politics are tremendous. Foremost is the All Progressives Congress’ (APC) abominable record in office. So far, President Buhari has not joined Tinubu on the hustings, which is probably a good idea. Buhari is a soporific speaker, does not seem to care who succeeds him, and boasts a horrendous economic record. Not only is the country economically worse off than when he took office almost eight years ago—according to the National Bureau of Statistics, “63% of persons living within Nigeria (133 million people) are multidimensionally poor,” —there is no arguing that it is less safe. Buhari himself has confessed to being desperate to retire to his farm once his term expires in May, and there are many Nigerians who wish he had done so eight years ago.

The Buhari administration’s failure has been a drag on the Tinubu campaign, though, curiously, not as much as one might have been led to expect.

Tinubu has, perhaps inevitably, also run into headwinds among the Yoruba political elite. In a widely circulated letter, former president Olusegun Obasanjo encouraged Nigerians to vote for Peter Obi, the Labour Party (LP) candidate. Ayo Adebanjo, leader of Afenifere, the apex Yoruba sociocultural group, is firmly opposed to Tinubu’s candidacy. Although Tinubu may still count on broad support among his Yoruba co-ethnics and will most likely capture majority of votes in the region, division among the Yoruba elite (partly about principle, partly a function of toes inevitably stepped upon as Tinubu clambered up the greasy pole) means that he will always go into battle knowing that he has at least one flank uncovered. While his antagonists see this as a disadvantage he might come to rue, his supporters point out that no Yoruba leader (not even the titanic Obafemi Awolowo) has ever boasted of the total allegiance of the Yoruba.

Where Tinubu faces the most consistent opposition though, is among the “Obi-dient,” the insurgency of enthusiastic, Web-wise, and mostly urban-based supporters of sixty-one-year-old Peter Obi. Insofar as the movement aggregates the disaffections and agonies of generations of Nigerians about the Nigerian state, it is safe to say that it predates the emergence of Obi as a presidential candidate to reckon with. To that extent, Obi is merely a vehicle of convenience for a political passion that will, in all probability, outlive him, especially if, as one might reasonably expect, he fails to muster enough support across the country to get him over the line. Whatever becomes of Obi, and regardless of his unseemly canonization by a cross segment of the Obi-dient, no one doubts that they, i.e., Obi-dients, have a legitimate point about the domination of Nigerian politics by an older generation that is perceived to be out of touch with the country’s lingering economic and political problems. Tinubu, whose influence was decisive in ensuring that Buhari, eighty this year, became president in 2015, is, rightly or wrongly, seen as the ultimate symbol of this geriatric hegemony.

The deeper sociocultural forces at work transcend Tinubu; the rise of the Obi-dients signals a shift in the tectonic plates of Nigerian politics, indexed in part by the arrival on the social scene of a new generation (the median age in Nigeria is 18.1 years) adept in the use of modern technology and impatient about the country’s constant blundering. This ascendant generation may not have changed the rules of the game just yet; but it is renegotiating the terms and shifting the contest to a different terrain.

The Obi-dients have raised a clamor. Tinubu will hope that they do not have enough right now to swing the momentum for an election that is bound to determine what becomes of his political empire, both nationally and regionally.