TWE Remembers: John Foster Dulles

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

Every day thousands of people fly into and out of Washington’s Dulles International Airport. Few of them think about the man for whom the airport is named, John Foster Dulles. He was born on this day in 1888 in Washington, D.C. Dulles may be unknown to most Americans today, but as Dwight D. Eisenhower’s secretary of state in the 1950s he was a titan of American foreign policy.

Dulles had good bloodlines. He was the grandson of one secretary of state, John W. Foster, who served under Benjamin Harrison. He was the nephew of another, Robert Lansing, who was Woodrow Wilson’s second secretary of state. His younger brother, Allen, was the first civilian director of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Dulles had impeccable credentials to go along with his impressive lineage. A Phi Beta Kappa at Princeton, he got his law degree from George Washington University. He served as one of Woodrow Wilson’s negotiators at the Paris Peace Conference that yielded the Treaty of Versailles. (It could not have hurt his effort to land the job that his uncle was the sitting secretary of state.) He later worked for one of New York City’s most prestigious law firms, Sullivan and Cromwell, eventually heading it up. He became a close confidante of New York governor Thomas Dewey of “Dewey Defeats Truman” fame. He advised Sen. Arthur Vandenberg during the 1945 San Francisco Conference that drafted the UN Charter. (Vandenberg was an official congressional observer for the U.S. delegation.) He briefly served as a senator from New York in 1949, filling out an unexpired term.

Dulles was deeply religious and a firm believer in American exceptionalism. He took pride in the fact that “nobody in the Department of State knows as much about the Bible as I do.” He came to office hoping to make the administration’s “political thoughts and practices reflect more faithfully a religious faith that man has his origin and destiny in God.” (Politics and religion mixed in American politics long before the rise of the so-called Religious Right.) Dulles’s deep religious beliefs left him suspicious of compromise and prone to self-righteousness, two flaws not lost on others. Winston Churchill occasionally mocked him as “Dullith” and once quipped that Dulles was the only bull that carried his own china shop with him. Eisenhower remarked that Dulles exhibited “a curious lack of understanding of how his words and manner may affect another personality.”

Dulles could be flexible, however, when it served his career goals. After World War II, he championed bipartisanship and worked closely with Harry Truman’s secretary of state Dean Acheson on a final peace treaty with Japan. But with the 1952 Republican Party platform decrying containment as a “negative, futile, and immoral” policy that abandoned “countless human beings to a despotism and Godless terrorism” and Richard Nixon, Eisenhower’s running mate, denouncing “Acheson’s Cowardly College of Communist Containment,” Dulles decided that containment was a defeatist treadmill policy that, “at best, might perhaps keep us in the same place until we drop exhausted.”

Dulles is associated with three major policy ideas. The first was called liberation or rollback policy. It held that rather than containing the Soviet Union the United States should roll back communist gains in Eastern Europe and elsewhere. During the 1952 campaign, Dulles vowed that “we can never rest until the enslaved nations of the world have in the fullness of freedom their right to choose their own path.” Dulles wanted a “policy of boldness” that would make enslavement “so unprofitable that the master will let go his grip.”

The other two ideas were massive retaliation and brinkmanship. Massive retaliation held that the United States should, in Dulles’s words, develop the ability “to retaliate instantly against open aggression by Red armies, so that if it occurred anywhere, we could and would strike back where it hurts, by means of our choosing.” Brinkmanship referred to the refusal to back down in a crisis, even if it meant risking war. As Dulles wrote, “the ability to get to the verge without getting into war is the necessary art. If you cannot master it, you inevitably get into war. If you try to run away from it, if you are scared to go to the brink, you are lost.”

Dulles’s talk of liberation, massive retaliation, and brinksmanship remained just that. When East Germans rebelled in 1953 and Hungarians revolted in 1956, Washington did not match its bold words with equal action. Yet neither Dulles (nor Eisenhower) suffered politically at home because they chose to sit on the sidelines. Indeed, as the historian Stephen Ambrose writes in The Rise to Globalism, Eisenhower and Dulles were popular precisely because “they were unwilling to make peace but they would not go to war.”

Dulles also led one of the more shameful episodes in American history, the purge of State Department officials suspected of being “disloyal.” The hunt for “subversives,” to borrow a favorite term from the era, found vanishingly few traitors but ruined the careers of many Foreign Service officers. Several of the State Department’s “Asia hands” were driven from the service because they made the mistake of correctly predicting the communist takeover of China. The result of the firings, as the journalist Theodore H. White wrote, “was to poke out the eyes and ears of the State Department on Asian Affairs, to blind American foreign policy.”

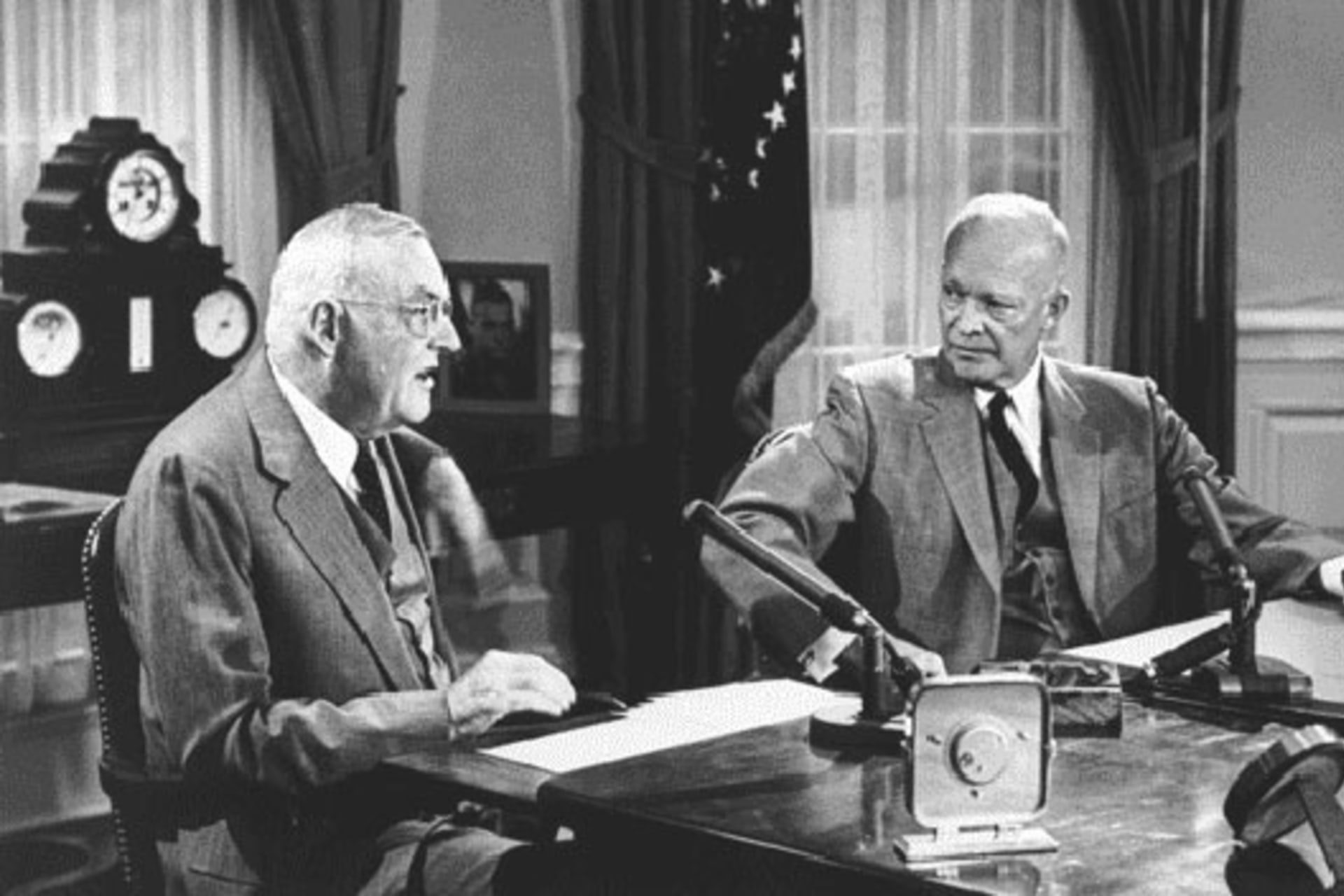

A final question is how much Dulles mattered to Eisenhower’s foreign policy choices. During the 1950s, Dulles received considerable credit. Ike’s own lack of oratorical grace—his speeches sometimes left his audiences wondering what he had just said—and his willingness to let Dulles be the public face of his foreign policy prompted much talk that the secretary of state dominated their partnership. Eisenhower himself bristled at such suggestions. He once remarked that he knew of “only one man . . . who has seen more of the world and talked with more people and knows more than [Dulles], and that’s me.”

Few historians today would argue that Dulles led Eisenhower. As Princeton University professor Fred Greenstein has written, Eisenhower was a skilled politician whose “hidden hand leadership” dominated policy making. Or as Richard Immerman has put it, although Eisenhower and Dulles “held strikingly parallel views . . . the documents confirm that it was the president who made the decisions.” All of which illustrates a general rule of American politics: a secretary of state—or any presidential adviser for that matter—shapes policy only the extent that he or she has the president’s ear.