TWE Remembers: Maj. Richard Heyser Flies a U-2 Over Cuba

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

The U-2 is a remarkable plane. It can fly at altitudes above 70,000 feet for hours at a time, and it gave the United States an intelligence advantage from the moment it became operational in 1956. (The U-2 is so good that upgraded versions continue flying missions even today.) Most Americans first learned of the spy plane’s existence in May 1960 when the Soviet military shot down Francis Gary Powers, embarrassing the Eisenhower administration and touching off a crisis in U.S.-Soviet relations. But an even bigger crisis between the two superpowers was triggered by a successful U-2 mission: Maj. Richard Heyser’s flight over Cuba on the morning of October 14, 1962.

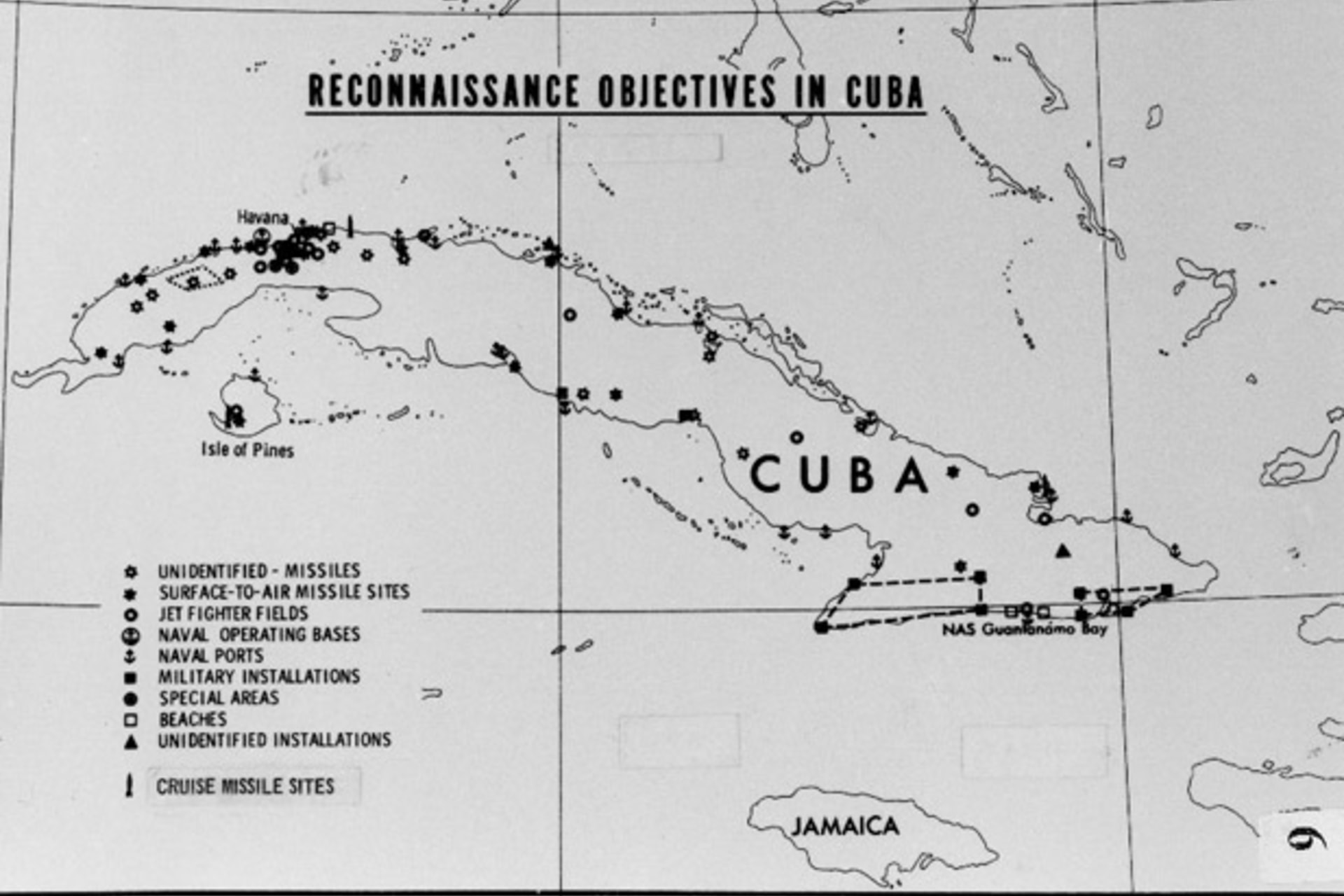

Major Heyser’s flight began at 11:30 p.m. the night before when he took off from Edwards Air Force base in the Mojave Desert in southern California. Bad weather had kept the thirty-five year-old Air Force veteran and native of Apalachicola, Florida waiting for four days to begin his mission, which was to fly over western Cuba looking for evidence of Soviet offensive weapons. U.S. officials had been worried for several months that Moscow was arming Cuba with weapons that could directly threaten the United States. Reassuring words from Soviet leaders—most recently and publicly from Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko speaking at the United Nations three weeks earlier—had done nothing to quell those fears.

The flight to Cuba took Heyser five hours. At 7:30 a.m., he began his reconnaissance run, approaching the island from the south. He was flying fourteen miles high, twice the altitude of commercial jet traffic. The weather over Cuba was picture perfect. As the U-2 entered Cuban airspace he switched on the plane’s camera. His job now was to fly a straight and steady course, which meant not letting

his eyes stray far from the circular airspeed indicator. He was flying at an altitude known to U-2 pilots as “coffin corner,” where the air was so thin it could barely support the weight of the plane, and the difference between maximum and minimum speeds was a scant six knots (seven mph). If he flew too fast, the fragile black bird would fall apart. If he flew too slow, the engine would stall, and he would nose-dive.

He scanned the sky for telltale wisps of smoke from Soviet surface-to-air missiles recently deployed on the island. If he saw a contrail heading in his direction, he was trained to steer an S-pattern, into the missile path and then away from it, so that the missile would zip past him, lacking sufficient power to adjust its course.

But no wisps of smoke appeared. It was an uneventful reconnaissance run. After six minutes and 928 photos, Heyser exited Cuban airspace. He adjusted course and headed for his final destination, McCoy Air Force Base near Orlando, Florida.

As Major Heyser underwent the standard post-flight debriefing, most Americans were only just beginning their Sunday. Church pews were filling up. Baseball fans were wondering if the weather would finally allow the New York Yankees and San Francisco Giants to play Game 6 of the World Series at Candlestick Park. Football fans eagerly awaited a slate of seven NFL games, including one that pitted the undefeated Green Bay Packers against the winless Minnesota Vikings. President John F. Kennedy was preparing to fly from Louisville, Kentucky to Buffalo, New York, where he would speak at the city’s annual Pulaski Day Parade.

What Americans didn’t know that Sunday morning in October was that the photos that Major Heyser had taken were being flown “with all deliberate speed” to the Naval Photographic Interpretation Center in Suitland, Maryland. Once the photos were developed and reviewed, the United States and the Soviet Union would suddenly be locked in a confrontation that would take them to the brink of war: the Cuban missile crisis.

For other posts in this series or more information on the Cuban missile crisis, click here.