Two Takes on U.S. Debt and the Debt Ceiling

Economists Benn Steil and Glenn Hubbard give their respective takes on the debt ceiling and the United States’ national debt.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Benn SteilSenior Fellow and Director of International Economics

By Benn SteilSenior Fellow and Director of International Economics

How to End Debt Ceiling Dramas and Bring Down Deficits

by Benn Steil

Two propositions should be of little controversy in Washington: that the United States government should always pay its debts, and that it should (at the very least) significantly slow the growth of the federal debt. Yet, when mixed together, these two propositions create a toxic political brew, as seen in the periodic debt-ceiling stand-offs between Republicans in Congress and Democratic administrations.

To end such stand-offs, the two issues need to be separated—permanently. To effect this separation, a credible process needs to be put in place both to prevent defaults and to reduce fiscal deficits.

Crises are typically defused when warring sides make concessions. But no side ever embraces concessions seen as forced upon it. In the case of the Cuban missile crisis, the Soviet Union agreed to withdraw its nuclear missiles from Cuba, and the United States agreed not to invade Cuba. But the United States also agreed, secretly, to withdraw its nuclear missiles from Turkey with a time lag (five months). Eventually the deal was going to become known (it stayed secret for twenty-five years), but by that time it was understood that the political atmosphere would be calmer and more accepting of the need for compromise. We need a comparable decoupling of concessions in the debt and deficit battles today.

The U.S. federal debt held by the public now amounts to nearly 100 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP), up twenty percentage points since the end of 2019. The pandemic was clearly the dominant driver of the rise, yet the trajectory remains upward. Over the past year, with unemployment averaging a near-postwar low of 3.6 percent, the federal budget deficit has been running at an enormous 8 percent of GDP. Based on both fiscal logic and historical experience, unemployment this low should be accompanied by a balanced budget. It would surely be desirable for Congress and the Joe Biden administration to take action now to bring that deficit down robustly and sustainably. Yet it is clear that the country cannot rely solely on the capital’s collective sense of prudence in order to make that happen. We need to take steps now, on a bipartisan basis, to lay the groundwork for meaningful, long-term fiscal reform.

Step one would be for Congress to pass some form of Debt Ceiling Reform Act—as has already been proposed by Democratic senator Dick Durbin and congressman Brendan Boyle. Such an act would put the burden on Congress, by two-thirds vote in the House and Senate, to stop the Treasury department from making legally authorized bill payments. As such a vote should never occur, Treasury would no longer need to undertake legally dubious work-arounds in order to make such payments. As a practical matter, debt-ceiling crises would become a thing of the past.

Step two would be for Congress to create a bipartisan commission along the model of The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, established in 2010 by President Barack Obama and chaired by former Republican Senator Alan Simpson and former White House Chief of Staff Erskine Bowles. Such a commission should, as with Simpson-Bowles before it, comprise an equal number of members, half of whom Democrats and half Republicans, from three groups: the Senate, the House, and the private citizenry. Unlike Simpson-Bowles, however, this new commission should be created by an act of Congress, rather than executive order, in order to establish a clear legislative commitment to act. The commission’s remit should be to produce a plan of spending and tax reforms in order to reduce the federal budget deficit by a set target figure over the coming ten years. The fiscal estimates needed to complete the commission’s work should be provided by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office. The commission’s plan would, in the end, be subjected to an up-or-down vote in Congress.

Within the commission there should be established working groups on revenue sources, discretionary spending, and mandatory spending. The last of these, which covers Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security, currently accounts for the lion’s share (63 percent) of federal spending. No meaningful fiscal reform can, given an aging population, sidestep the need for greater revenue and/or cost cuts to keep government health care and retirement programs viable into the distant future.

The Simpson-Bowles report, calling for specific actions to reduce the deficit by $4 trillion over the subsequent decade, was in December 2010 approved by eleven of the commission’s eighteen members. This number, unfortunately, fell short of the fourteen-member supermajority required to submit the report to an up-or-down vote in Congress. The commission was therefore a failure, in that it did not generate the legislation necessary to effect its plan and to reduce the deficit. But it did demonstrate that a bipartisan panel could, in fact, produce significant budgetary compromise even in an era of hyperpartisanship.

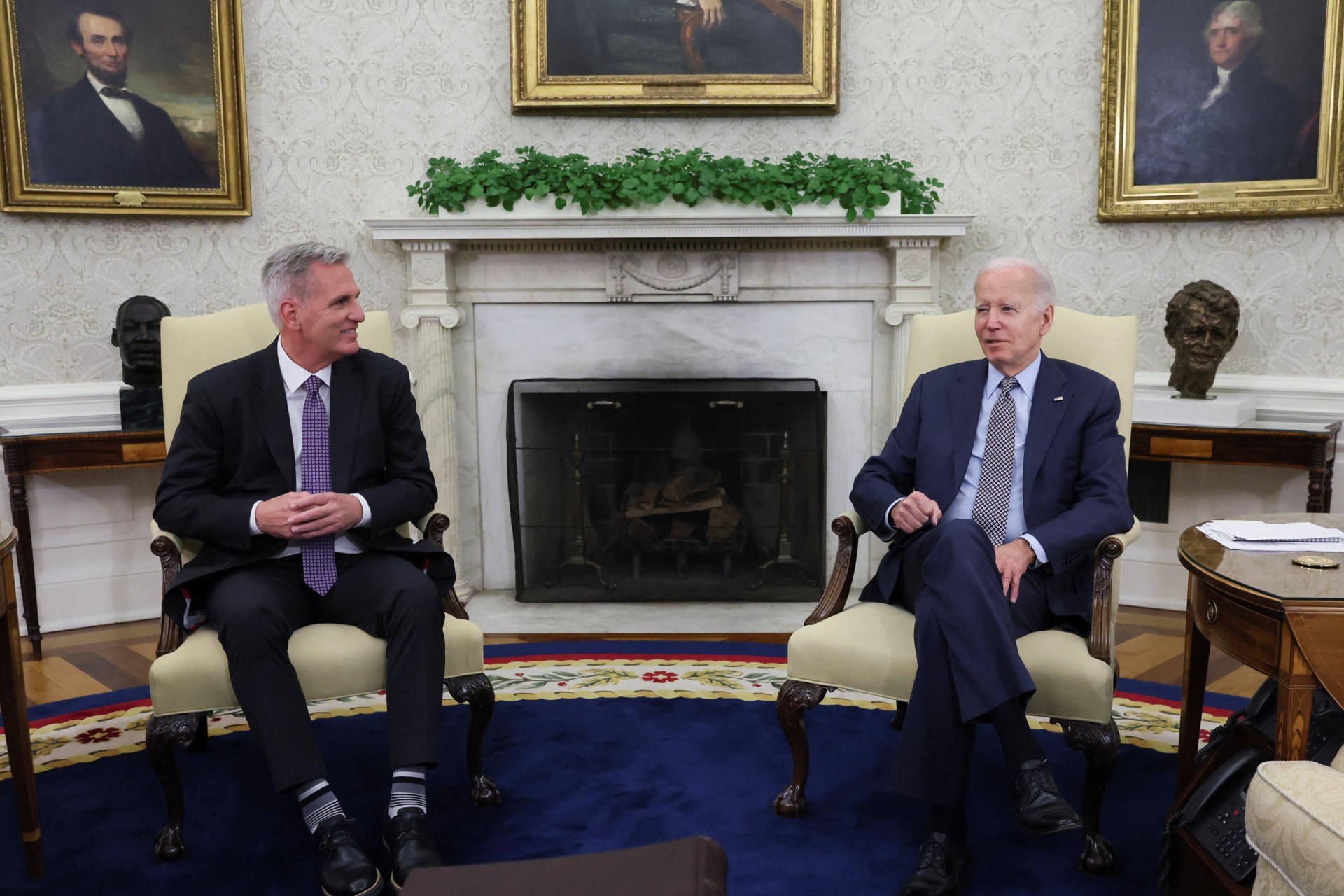

With the right composition, bringing in men and women committed to finding common ground in the public interest, and a modest adjustment to the supermajority threshold for plan approval (say, eleven instead of fourteen), a bipartisan budgetary commission can work today. President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy showed that, when the stakes were clear and high enough, fiscal compromise in Washington was indeed still possible. It is time to build on that momentum in order to end debt-ceiling brinkmanship and to put the country back on a course of fiscal sustainability.

After the Debt Ceiling

by Glenn Hubbard

With the debt ceiling increase signed into law by the president, financial markets are breathing easier. The debt ceiling battle seemed like an action thriller, a doomsday negotiation from the beginning, holding out the specter of major economic costs accompanying any U.S. Treasury default to obtain very modest spending concessions with an increase in the debt ceiling. But this action thriller description misses the real plot.

What if the real story goes the other way around? What if the short-term relief from fiscal tension masks the real problem—a drama whose ending grows more dire with each short-term extension and breather.

U.S. fiscal policy is on an unsustainable path. The U.S. debt-to-gross domestic product ratio, about 25 percent in 1980, now stands at 93 percent, nearly as high as the close of the Second World War. Long-term budget forecasts from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) show gradual increases in federal spending relative to GDP. Putting two and two together, today’s high debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to rise…until something gives.

Both the World War II figure and the CBO long-term outlook are important benchmarks. Prior to the 1970s, a plot over time of U.S. federal debt-to-GDP showed peaks fueled by wartime borrowing, with subsequent declines driven by lower federal spending and economic growth. The rapid fall in the debt-to-GDP ratio in the first decades after World War II illustrates this self-reinforcing corrective pattern. Beginning in the 1970s and accelerating over time, social spending on Social Security and Medicare revealed two changes. First, such spending was different from traditional discretionary federal spending on defense, public goods, and a modest social safety net. Second, no self-correcting mechanism has been present – treated as ‘mandatory’ spending, these programs grow unchecked, changing the debt-to-GDP picture from peaks and declines to an upward march.

While the debt ceiling battle’s theatrics ring farcical, the underlying long-term fiscal drama is serious. While a fiscal collapse—with a sharp rise in interest rates and sudden fiscal contraction—is unlikely, three more gradual, but painful adjustments to close the fiscal gap merit concern. The first is a path of very significant tax increases, with negative consequences for economic growth and living standards. The second is crowding out of “discretionary” spending—on defense, research, and education—to protect spending on interest and old-age entitlement programs. And finally, entitlement spending growth will decline, reducing the generosity of Social Security and Medicare benefits for many or even most Americans. A combination of these adjustments can emerge, as for example, in the Bowles-Simpson Commission report, promptly ignored by President Barack Obama and Congress. All possibilities share a common thread—the longer the delay in action, the greater the economic and social pain of fiscal contraction. In contrast to the debt ceiling’s short fuse to resolution, inaction’s long fuse to fiscal disruption generates longer-term pain.

Is there a way out of the fiscal crisis lurking beneath the debt ceiling drama? Yes, but it won’t be easy. The first step is to provide more information for policymakers and the public about the size of the fiscal hole. Both current “on budget” and “off budget” measures of deficits and debt and astronomical present value estimates of unfunded liabilities of Social Security and Medicare lack focus to drive public concern and legislative action. More useful would be to explain a path of spending cuts and/or tax increases necessary to stabilize the federal debt-to-GDP ratio at its current level or a lower one. Relatedly, the U.S. Treasury estimates that deficit reduction averaging over 4 percent of GDP each year over the next 75 years will be required to restore fiscal sustainability. Such changes are large—equivalent to over one-fifth of the percent value of non-interest spending.

Putting such information to use, the administration could be required to set a spending path and deficit targets to make progress with review and criticism from, for example, the Congressional Budget Office, which has its golden anniversary in 2024. As long as the budget path is adhered to, debt ceiling extensions could be clean. This enhanced budget review and criticism has been used with success in Sweden and the United Kingdom.

Good steps, but budget rules may be needed. An introductory step is to guard against making fiscal matters worse. That is, any budgetary measure increasing the debt-to-GDP ratio—including increases in unfunded liabilities of Social Security and Medicare would be offset by other spending reductions or tax increases. A more strenuous rule would be a spending limitation. One version, suggested by Timothy Kane and me, would be to limit real spending in a given year to the average of real spending over the previous seven years. Either rule could be sidestepped by a supermajority vote of Congress in the event of a significant economic downturn or national emergency.

The eventual fiscal adjustments arising from a continued failure to act are economically and socially painful. But while budget reforms are required, they raise a question: why would politicians agree to a reformed system that constrains their discretion? The answer lies in linking clean increases in the debt ceiling—politically valuable to the governing party—to reform. And, again, reform can begin modestly—with greater information and public dialogue, a budget framework with targets, and a beefed-up budget office to hold a mirror up to government action or inaction.

This pivot spares us the tragedy accompanying fiscal unsustainability and the farce of the debt ceiling tug of war. And it gives our balancing of budget priorities a needed next act.

Mr. Hubbard, a professor of economics and finance at Columbia University, was Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President George W. Bush.

This post was written for the Council on Foreign Relations’ Renewing America initiative—an effort established on the premise that for the United States to succeed, it must fortify the political, economic, and societal foundations fundamental to its national security and international influence. Renewing America evaluates nine critical domestic issues that shape the ability of the United States to navigate a demanding, competitive, and dangerous world. For more Renewing America resources, visit https://www.cfr.org/programs/renewing-america and follow the initiative on Twitter @RenewingAmerica.