More on:

When President Bill Clinton was trying to persuade Congress to pass the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1993, administration officials frequently made the claim that each additional $1 billion in exports would produce 17,000 new jobs in the United States. Implicit in the claim was the idea that NAFTA and other free trade agreements would trigger a big growth in exports, and that exports would be an engine of job creation.

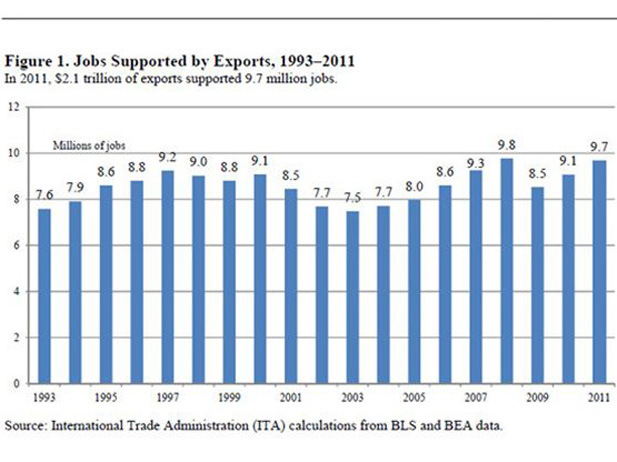

The claim turned out to be half true. U.S. exports to Mexico surged, growing nearly 400 percent since 1993, and Mexico is today the second largest recipient of U.S. exports after Canada. Overall, the value of U.S. exports to the world has increased nearly three-fold, from $627 billion in 1993 to $1.65 trillion last year. But the promised job growth never came; the number of U.S. jobs supported by exports is up only marginally from 1993, and is roughly the same number as existed in the mid-1990s.

What happened? A fascinating new paper published last month by the Commerce Department’s Office of Competition and Economic Analysis – entitled "Jobs Supported by Exports, 1993-2011" – has some compelling answers.

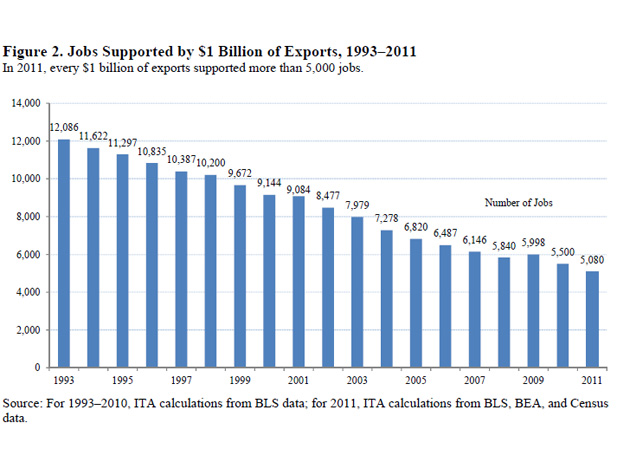

In 1993, which turns out to be the first year for which data are available, the report says that each $1 billion of exports supported just over 12,000 jobs. (I have not yet been able to determine the discrepancy from the 17,000-job figure used back in 1993.) By 2011, however, that same $1 billion in exports supported only 5,000 jobs. About one-quarter of the difference is due to rising prices over the past two decades, but most of the difference is the result of higher productivity in export-intensive sectors which has reduced the need for labor.

That makes perfect sense. Some three-quarters of U.S. exports are in the goods sector, one-third of those directly in manufacturing, and many of the rest in industries that support manufacturing exports. From 1993 to 2011, labor productivity in the manufacturing sector doubled, compared with just a 50 percent increase in overall productivity. In other words, today it takes many fewer workers than in 1993 to produce the same $1 billion in exported products.

The consequence is that even rapidly growing exports have created very few new jobs. Given the average annual productivity improvements over the past two decades, exports need to grow by roughly 5 percent each year just to support the same number of jobs. Even with the extremely strong U.S. export performance over the past two decades, the total number of U.S. jobs supported by exports in 2011 -- 9.7 million jobs – is up just 27 percent from the number of jobs in 1993.

Source: "Jobs Supported by Exports, 1993-2011"

The implication of these figures is fairly stark. As the Obama administration has noted often, export jobs are good jobs – employees in export-intensive industries earn some 20 percent more on average than comparable workers in industries that produce goods and/or services only for the domestic market. But there are simply too few of them to make a significant dent in unemployment, or to lift household incomes which have been flat for the past two decades. The largest number of export jobs are in technology-intensive industries such as aerospace, semiconductors, and motor vehicles.

The Obama administration, under its National Export Initiative, set a goal of doubling the value of U.S. exports from 2010 to the end of 2014. Despite a slowdown in exports this year due to weakening economies in Europe and parts of Asia, the administration remains roughly on track to reach that goal. But even with that success, exports are doing little to address the administration’s core concerns – high unemployment and a dearth of well-paying jobs.

If export competitiveness can’t solve the jobs crisis, then the answer needs to lie closer to home. While it still makes sense to use every policy tool available to expand export-related jobs, the bigger challenge is to raise wages in the industries where most Americans work and where job numbers are still growing – service jobs that do not face international competition. Robert Kuttner has some interesting ideas on how this might be done in a new paper for the New America Foundation. The problem needs far more attention than it has received so far.

More on: