Brent Scowcroft was, above all, a realist

Brent Scowcroft, a model national security adviser, taught us much about U.S. foreign policy

Originally published at The Washington Post

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Richard HaassPresident Emeritus, Council on Foreign Relations

By Richard HaassPresident Emeritus, Council on Foreign Relations

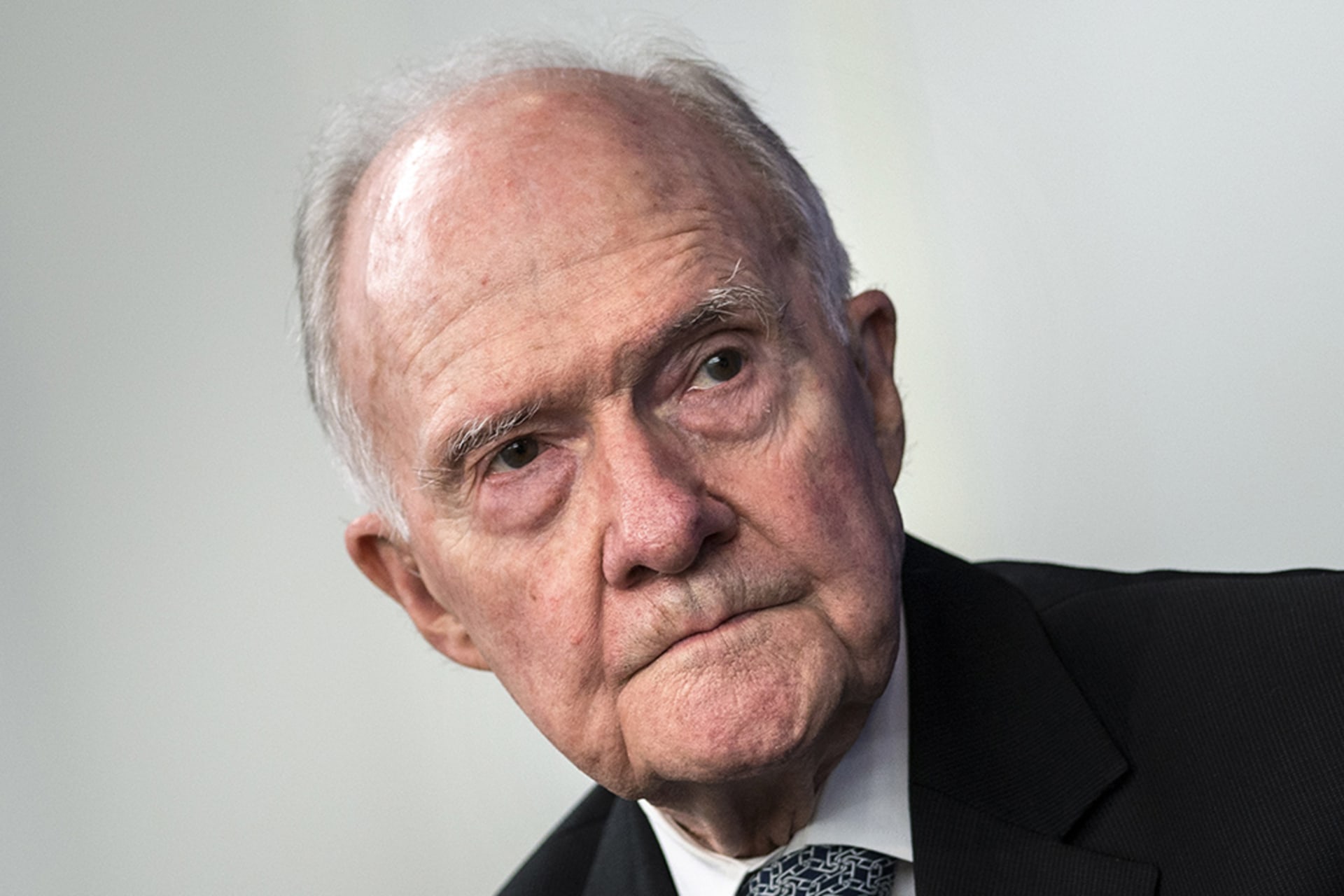

Brent Scowcroft’s passing at 95 is a reminder of how far the United States has come — and, in some ways, fallen — since the early 1990s. He was one of the wise men who guided the United States through the Cold War, and he was someone who believed passionately that this country could be, and often was, a force for good in the world.

A military officer by training, Brent served as national security adviser to Gerald Ford and George H.W. Bush, the only man who held the job twice. He was arguably our most effective national security adviser, and it is unsurprising that nearly all his successors have cited him as a role model.

Born in Utah in 1925, he graduated from West Point in 1947. A plane crash in 1949 ended his dream of becoming a fighter pilot. Instead, he went on to get a masters and doctorate in international relations, served as assistant air attache in Belgrade, and later became military assistant to President Richard M. Nixon and then deputy to Henry Kissinger at the National Security Council. He went on to succeed Kissinger at the NSC under Ford, at which time he retired from the Air Force with the rank of lieutenant general.

There have been some two dozen national security advisers, some successful and others not. Brent seemed to have been born for the job. History shows just how difficult it is to do it well. Every person who holds the job must wear two hats. The first is to provide the president with advice from every corner of the government on foreign policy problems. The right questions must be asked and answered rigorously. Meetings must be convened, issues debated, decisions reached, and then implemented and reviewed. A disciplined process can reduce the chance of major errors and promote consistency. As we have seen, the absence of such process can be disastrous.

But the national security adviser is also a private counselor to the president — someone who provides advice on all aspects of foreign and defense policy, free from departmental prejudices. The best who take the job tell the president what he needs to hear, not wants to hear. This may seem a cliche, but the willingness to do so is rarer than it should be.

It takes a human being with rare character to represent faithfully the views of others even when disagreeing with them. Brent was so skilled at this that personalities as strong as James Baker, Richard B. Cheney and Colin Powell were all comfortable with him making their case to Bush when circumstances warranted.

His temperament leaned to the conservative: He understood that any course of action might make a situation worse as well as better. Some might argue this led him to be too cautious, as in the former Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, where he feared the United States was heading down a path that would get it bogged down in that country’s deep divisions. Such caution, though, seems understandable when one considers that the most costly errors of modern U.S. foreign policy — in Korea in 1950, when we moved north of the 38th parallel in an ill-advised attempt to reunify the peninsula by force, in Vietnam, and most recently in Iraq and Afghanistan — were born more of outsize ambition than anything else.

But Brent was not cautious when he determined inaction would be more costly than resolve, and when he believed vital U.S. interests were at stake. He was among the first to urge Bush to make clear that Saddam Hussein’s aggression against Kuwait would not stand. In no small part because of his advice, it did not.

Brent was, above all, a realist. He believed the purpose of U.S. foreign policy should be to shape the foreign policies of others, most often through diplomacy. Regime change was rarely a serious option. He had a strong sense of the limits of what we could accomplish in the world, especially when it came to making others more like us. Such thinking was behind his willingness to maintain a relationship with China despite the brutality of the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, to argue against marching on to Baghdad in the aftermath of Operation Desert Storm in 1991, and to oppose the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

He did not care that many of his stances were controversial; he was not worried for his reputation. He promoted his views firmly but without rancor. Differences were just that, differences, and did not make for enemies.

Much of this sounds distant from America today, which is our loss. We could regain a great deal just by reminding ourselves of what Brent Scowcroft did and how he did it.