The Evolution of U.S.–Vietnam Ties

Published

Updated

Once locked in war, Vietnam and the United States have built mature ties rooted in mutual economic and security interests.

What are backgrounders?

Authoritative, accessible, and regularly updated Backgrounders on hundreds of foreign policy topics.

Who Makes them?

The entire CFR editorial team, with regular reviews by fellows and subject matter experts.

Introduction

Four decades after the end of the Vietnam War, the relationship between the United States and Vietnam has changed remarkably. The former adversaries have pushed past their turbulent history to forge strong trade linkages and security cooperation in recent years. This rapprochement, as well as Vietnam’s efforts to court other Asia-Pacific powers, such as India and Japan, have largely been driven by Vietnam’s concerns about Chinese primacy in the region, particularly its assertive behavior in the South China Sea. Given the dynamics, analysts expect Vietnam and the United States to foster a deeper partnership in the years ahead. However, the relationship faces constraints, including Hanoi’s state-led capitalism and its residual distrust of Washington.

Emerging From War

Vietnam declared its independence from French colonial rule in 1945 after Japan’s occupation ended with its surrender to the Allies. This set the stage for the First Indochina War (1946–1954). In 1950, Vietnamese forces in Hanoi were recognized by China and Russia, while the United States and the United Kingdom recognized the government based in Saigon (today’s Ho Chi Minh City). Washington’s involvement in Vietnam escalated with the provision of military assistance first to French forces, followed by Saigon-based President of Vietnam Ngo Dinh Diem’s anti-communist forces after the country’s north-south division. U.S. troops formally deployed in 1964 with the stated purpose of stemming the spread of communism. Years of brutal battles culminated in the withdrawal of U.S. forces and the signing of the Paris Peace Accords [PDF] in 1973; the United States evacuated its personnel in 1975 as North Vietnam invaded the South and reunited the country.

U.S. casualties were 58,220 dead, around 2,600 missing, and more than 150,000 wounded [PDF], and there were wrenching domestic divides over the purpose and conduct of the war. For Vietnam the destruction was massive, with an estimated two million civilian deaths and an additional one million military deaths, as well as lasting environmental effects from the use of herbicides, such as Agent Orange, and unexploded ordnance scattered throughout the country. Washington severed diplomatic ties after the war’s end and imposed a full trade embargo.

Also aggravating relations between Vietnam and a number of nations was its campaign in Cambodia. Skirmishes along the western Vietnamese border with Cambodia expanded into a full-scale conflict in December 1978. Vietnamese troops deposed Cambodian totalitarian leader Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge—its repressive regime was responsible for a genocide that killed nearly two million people—and installed a new government in Phnom Penh that would maintain power for a decade. The Vietnamese invasion triggered a retaliatory attack by China on its northern border in 1979 and widespread international isolation.

From the late 1970s through the mid-1980s, Vietnam’s economy was stretched thin as a result of a large military budget dedicated to activities in Cambodia and shortcomings in its command economy [PDF]. These hardships led to a heavy reliance on the Soviet Union. After China’s economic reforms in the 1970s and as the Soviet Union began to relax state control over its own economy in the 1980s, Vietnam began to explore ways to end its isolation.

The Path to Normalized Relations

One of the first hurdles to be cleared in restoring U.S.-Vietnam relations was cooperation on returning the remains of U.S. prisoners of war (POW) and missing in action (MIA) personnel. By the end of the 1980s, recovery efforts resumed with processes established for searches across the country by U.S. teams. This progress led to the opening of a field office for the United States Office in MIA Affairs in Hanoi under the George H.W. Bush administration in 1991, the first official postwar U.S. presence in Vietnam. This outpost, combined with a special temporary U.S. Senate committee set up to investigate POW/MIA-related issues, helped build momentum to normalize relations.

Securing a Cambodian peace plan was the second linchpin. Although occupying Vietnamese forces backed a new government in Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge still controlled part of the country while in exile in Thailand, and civil conflict was common throughout the 1980s. Peace talks begun in Paris in August 1989 ultimately led to the signing of an accord [PDF] in 1991. This initiated a cease-fire and installed the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia, the first UN peacekeeping operation to oversee the administration of a country and to organize and conduct a national election. Vietnam’s withdrawal of occupying forces in Cambodia enabled countries including the United States to repair diplomatic ties with Vietnam. Washington lifted travel restrictions against Vietnam in 1991, the U.S. State Department and the Vietnamese Foreign Ministry opened offices in each other’s capitals in 1993, and in 1994 President Bill Clinton lifted the trade embargo. These incremental steps created a favorable environment for Clinton to normalize relations in 1995.

Economic Linkages

Vietnam’s major economic reforms, launched in 1986 to boost the country’s underperforming economy, signaled an eagerness to restore international ties. The reforms, known as Doi Moi, prioritized building a market economy and creating opportunities for private-sector competition. Previously, the command economy had placed disproportionate importance on heavy industry while sectors such as agriculture struggled.

The introduction of a market economy in Vietnam, a country of now more than ninety-five million people, attracted sizeable international investments. After restoring ties, Washington and Hanoi worked for nearly five years to negotiate a bilateral trade agreement that came into force in 2001. The deal lifted many nontariff barriers [PDF] to trade, including quotas, bans, and import restrictions; lowered tariffs from an average of 40 percent to 3 percent on a variety of goods, including agricultural and animal products and electronics; and granted Vietnam conditional most-favored-nation trade status, a critical benchmark for accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO). After Vietnam joined the WTO in 2007, the two countries set up a forum to discuss Vietnam’s WTO commitments and additional investment and trade liberalization.

The Barack Obama administration championed the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a free trade agreement that included a dozen countries in the Asia-Pacific, including Vietnam, as a lynchpin of a U.S. strategic pivot to the region. Analysts said that Vietnam, which had the lowest per capita gross domestic product of all the signatories, was likely to be the greatest beneficiary of the pact, especially by gaining preferential access to the U.S. market. However, President Donald J. Trump, who claimed the deal would undermine the U.S. manufacturing base, withdrew the United States shortly after he took office in 2017.

Human rights advocates say the U.S. reversal dealt a blow to trade unionists, environmentalists, and other activists in Vietnam, who saw the TPP as helping to push a wave of wider reforms. “Pulling out of the TPP has been a big setback,” said Brad Adams, who leads Human Rights Watch’s Asia division, on the ripple effects for Vietnam’s activist communities.

Vietnam and the ten other parties to the TPP moved forward on a trade agreement without the United States, known as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Vietnam became the seventh country to ratify the pact, in November 2018. The agreement reduces tariffs in the Asia-Pacific and has provisions to improve labor conditions and boost privatization, but it is too soon to evaluate CPTPP’s consequences for Vietnam. Signatories granted Vietnam a three-year grace period to comply with the agreement’s labor provisions, which call for the introduction of independent unions.

Nevertheless, economists expect trade with the United States to continue thriving. Bilateral trade in goods between has soared since diplomatic normalization, from $451 million in 1995 to more than $60 billion in 2018. The United States is now the top destination for Vietnamese goods, including textiles, electronics, and animal products such as seafood. Top U.S. exports to Vietnam include cotton, computer chips, and soybeans.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Foreign Trade.Embed

A number of challenges loom over the budding commercial relationship. As he has with several other U.S. trading partners, President Trump has taken issue with the U.S. trade imbalance with Vietnam, which climbed to an estimated $39.5 billion in 2018. (This deficit is in goods. U.S. service exports to Vietnam were estimated to be $2 billion in 2015.) Washington has also cited other barriers to trade [PDF] with Vietnam, including inadequate intellectual property protections and food safety regulations, restrictions to the country’s internet access and digital economy, and other general governance issues, including a lack of transparency and accountability in the public and private sectors.

Growing Security Contacts

Washington and Hanoi have also made significant headway on the security front. Early defense ties were forged through the recovery of U.S. MIA personnel and included cooperation on search and rescue operations, environmental security, and demining; Vietnamese attendance at U.S. Pacific Command conferences and seminars; and high-level military exchanges. In 2016, Washington lifted a decades-long ban on lethal arms sales to Hanoi.

The security relationship has focused on enhancing exchanges between the U.S. and Vietnamese coast guards and the provision of patrol vessels. In 2018, the USS Carl Vinson, a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier, made a historic port call in Vietnam, the first docking of its kind since the end of the war in 1975. The same year, Vietnam participated for the first time in the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC), maritime military exercises hosted biennially by the United States. (The country was an observer in 2012 and 2016.)

Vietnam has shown the fewest illusions about the implications of China’s rise.

Joshua Kurlantzick, Council on Foreign Relations

The impetus for much of this activity has been China’s increasingly assertive stance in the region, especially in the South China Sea, where Hanoi and Beijing have competing maritime claims. Tensions between the neighbors reached a climax in 2014 when China deployed an oil rig into disputed waters, a move that prompted widespread anti-China protests and violence across Vietnam. Periodic anti-China protests continue to erupt in Vietnam.

As a result, Vietnam has increasingly viewed its security cooperation with the United States as a check against Chinese assertiveness. “Vietnam has shown the fewest illusions about the implications of China’s rise, and the greatest willingness to employ tough, sophisticated strategies to prevent Chinese dominance of the South China Sea and the region more generally,” writes CFR’s Joshua Kurlantzick.

Though defense and security cooperation has come a long way in the more than twenty years since the normalization of relations, obstacles remain. Lingering Vietnamese distrust of U.S. intentions, a strong sense of independence and nationalism, and concerns over provoking Beijing have restrained Hanoi from swiftly expanding security ties with Washington.

Discord on Human Rights

Vietnam’s poor record on human rights is a recurrent source of contention with some members of the U.S. Congress, as well as with other governments and watchdog groups. The country is still governed by a one-party, authoritarian system that suppresses dissent, including from the political opposition, independent religious communities, bloggers, journalists, and human rights advocates and lawyers. Authorities carry out arbitrary arrests and detentions [PDF] and extrajudicial killings; freedoms, such as those of religion, assembly, and speech, are highly restricted; and the judicial system lacks transparency [PDF] and its independence is compromised, according to reports by the U.S. State Department and international rights organizations.

Though the Vietnamese government has convened regular human rights dialogues with the United States and occasionally frees political prisoners, it is consistently rated poorly by international rights monitors. Vietnam ranked 175 out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders’ 2018 World Press Freedom Index, only besting China, Syria, Turkmenistan, Eritrea, and North Korea. The advocacy group Freedom House classified Vietnam as “not free,” receiving a 20 out of 100 in its annual report.

A Burgeoning Partnership

U.S.-Vietnam relations are expected to continue on a positive trajectory. While disagreements over the trade imbalance could temporarily stall progress, China’s growing influence in the region will likely push U.S. and Vietnamese strategic interests closer together.

Vietnam holds a key to the regional balance of power.

Alexander Vuving, Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies

Hanoi was the site of the second U.S.-North Korea summit in February 2019. The Southeast Asian nation served as the host for a variety of reasons, including generally amiable ties with both Pyongyang and Washington and the opportunity to showcase its economic success as an alternative course for North Korea. Hanoi’s role in the summit reinforced shared interests in the U.S.-Vietnam relationship and demonstrated Vietnam’s desire to be a more influential player in regional diplomacy. “Vietnam holds a key to the regional balance of power,” writes Alexander Vuving, an expert on Asia security at a Hawaii-based U.S. Defense Department institute.

Still, Vietnam’s defense policy is based on the “three nos” principle: no military alliances, no foreign troops stationed on Vietnamese soil, and no partnering with a foreign power to combat another. Yet, some analysts have questioned whether Vietnam should revisit its non-alignment policy. While it is elevating ties with the United States, Vietnam is also building relations with the European Union, Japan, and India in a bid to diversify its partnerships and balance its relations with both China and the United States.

Recommended Resources

CFR’s Joshua Kurlantzick says the United States should bolster ties with Vietnam as a model for U.S. relations with other Southeast Asian states as part of its Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy.

The Congressional Research Service details the economic and trade components [PDF] of the U.S.-Vietnam relationship.

Carlyle A. Thayer analyzes the shifts in Vietnam’s foreign policy amid increasing competition between the United States and China.

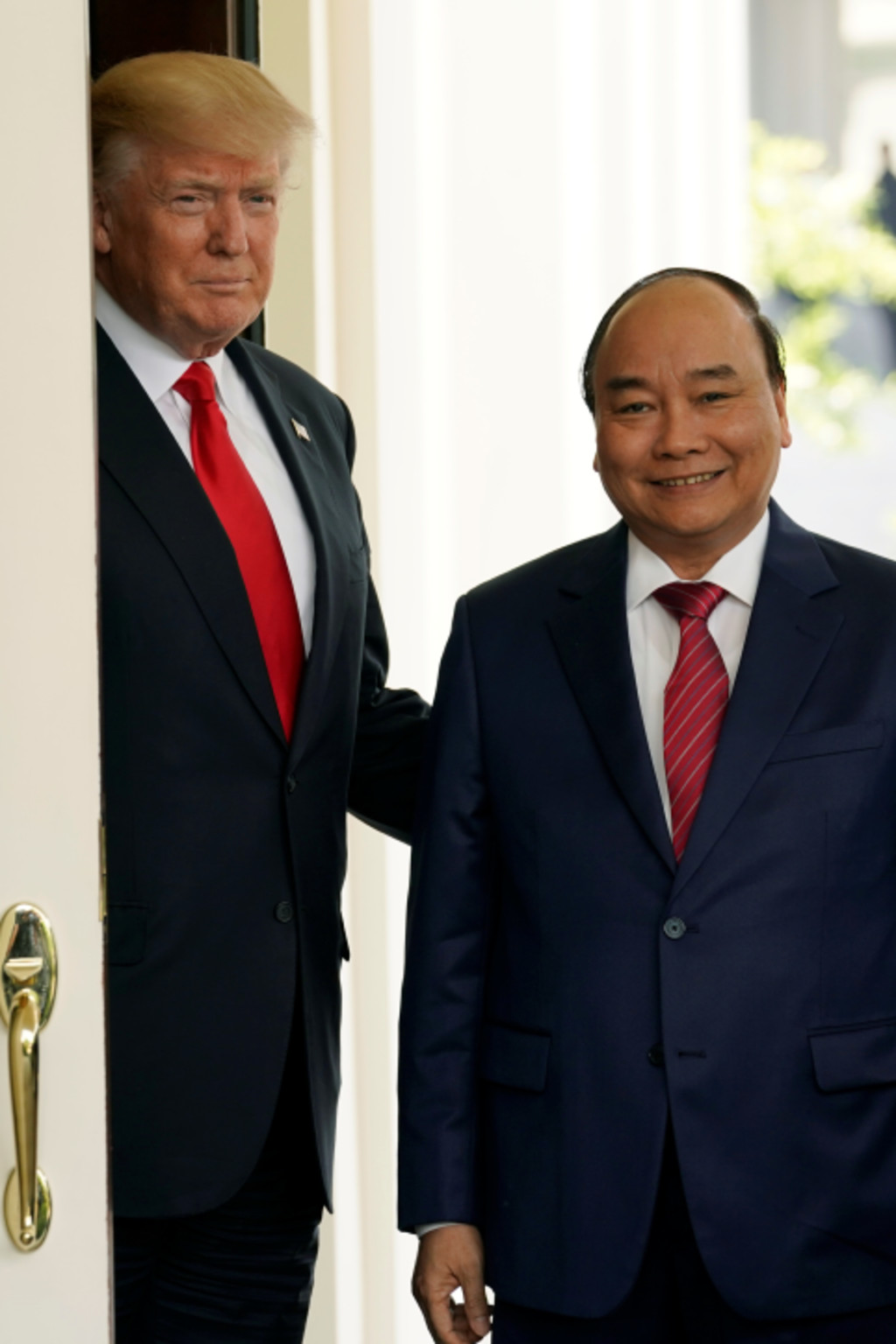

U.S. President Donald J. Trump issued a joint statement with Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc outlining ways to enhance the countries’ partnership in May 2017, and a second statement with Vietnamese President Tran Dai Quang in November 2017, during Trump’s visit to Asia.

Alexander Vuving argues for a stronger relationship between Washington and Hanoi to counter Chinese dominance in Asia.

The U.S. State Department describes the Vietnamese government’s restrictions [PDF] on the political rights and civil liberties of its citizens.t

Colophon

Staff Writers

- Eleanor Albert

Additional Reporting

Header image by Kevin Lamarque/Reuters.