Doesn’t a smaller (external) deficit mean less dependence on (external) creditors, including China?

More on:

There is a common argument that the US depends more on China now than before because the US needs to issue so many Treasury bonds to finance its fiscal deficit.

I disagree, for two reasons:

First, the trade deficit is down significantly, so the amount that the US needs to borrow from the rest of the world has fallen. That means less dependence on external creditors. The fiscal deficit -- obviously -- is much bigger now than it was a year ago. But inflows from the rest of the world can finance a private sector deficit as well as a public sector deficit. Private borrowing in the US is way down - and that has pulled total US borrowing from the rest of the world down even as the fiscal deficit rose. After crises in Asia in the 1990s and in Eastern Europe and the US in this decade, there should be little doubt that external deficits that have their roots in excessive private borrowing are also risky.

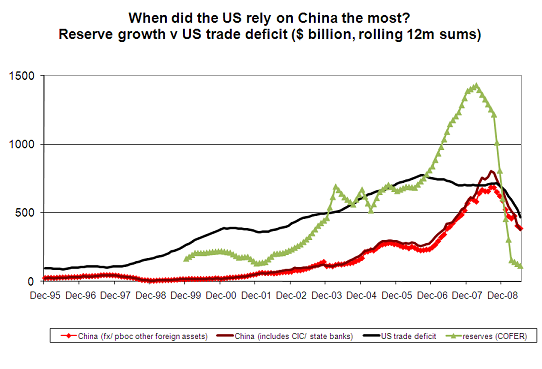

In my view, the US was more dependent on central banks in general and China in particular for financing back in 2006, 2007 and the first part of 2008 -- when the US trade deficit was larger than it is now and emerging market reserve growth was higher than it is now.

Second, the majority of the fiscal deficit isn’t being financed by foreign central banks. That’s a key change. Indeed, the rise in the Treasury’s issuance of long-term debt has come even as central bank demand for long-term debt has fallen. That key fact gets lost amid the general sense that the US must be relying more on China now than in the past because the US government is borrowing more.

The evidence? Three additional charts.

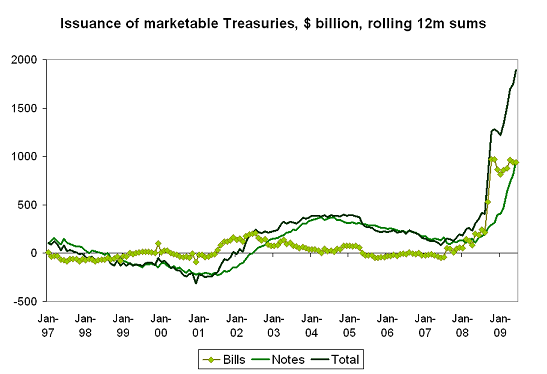

The US government clearly is borrowing a lot more -- as we all know. The stock of outstanding marketable Treasuries increased by close to $2 trillion over the last 12 months of data (June 2008 to June 2009). Some of those Treasuries were issued to finance the Fed’s actions as a lender of a last resort -- and some were used to finance the TARP. But more and more are being issued to finance the fiscal deficit.

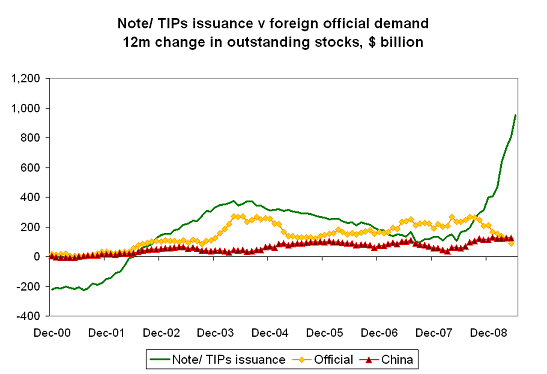

Give US debt managers a bit of credit. Over the last several months, they have sold more notes and fewer bills, financing more of the deficit with longer-term borrowing. That is good debt management. In the month of June, they sold close to $220 billion of notes while reducing the stock of outstanding bills by $60 billion. And they did so in a market where central banks remain reluctant to buy long-term US Treasury bonds, so most issuance is being bought by private investors.

When I look at a chart showing note issuance v estimated official demand, I don’t see any evidence that US dependence on foreign central banks -- or China -- or financing is rising. Rather I see evidence that the US is relying more on private demand for long-term Treasuries to finance its deficit.

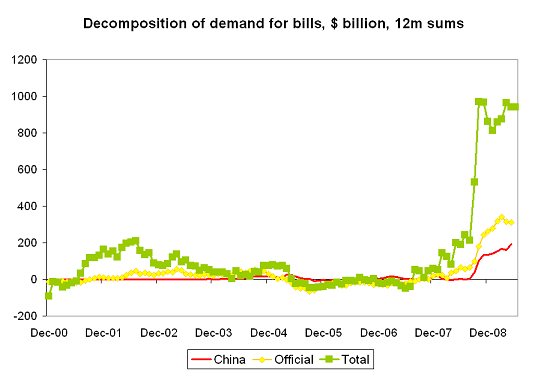

To be sure, it is important to look at the market for short-term Treasury bills as well -- and there is now doubt that central banks are buying more bills. China alone added about $200 billion to its stock of bills over the last 12 months of data (May 2008 to May 2009 in this case), taking up about 1/5 of the increase in the outstanding stock of bills over this time.

But the price of bills is largely set by US short-term policy rates; central bank demand there has less impact on key market rates than central bank demand for longer-dated Treasuries.

A few caveats.

Global reserve growth has fallen by more than Chinese reserve growth; China clearly still matters for the financing the US external and fiscal deficit -- though it is not currently playing the same outsized role it played back in late 2007 and early 2008.

The data over the last 3 months isn’t quite as clear as the data over the last 12 months as reserve growth has resumed, and there are signs that central banks are starting to buy Treasury notes again. Though they still need to prefer the shorter-dated notes, i.e. two and three year notes.*

And clearly China holds enough Treasuries (and Agencies) that if it ever started to sell -- really sell -- it would move the market. Any single investor that controls a $1.5 trillion dollar portfolio -- actually now more like a $1.6 trillion dollar portfolio -- can move the market if it abruptly changes its behavior. When central banks stopped buying Agency bonds last fall it had an impact.

But we shouldn’t ignore the adjustment that has happened. A smaller trade deficit means that the US relies less than before on inflows from the rest of the world . That’s progress.

The goal should be to maintain that progress -- and not go back to a world where the US was running a far larger external deficit than it is now. Those deficits came at a time when private markets wanted to finance the fast-growing emerging world, not the slow-growing US. The gap was filled by truly enormous inflows from the world’s reserve managers -- and China -- into US markets. Those inflows were far bigger than in the inflows we observe now. Just look at global reserve growth then. But those inflows were into a host of different markets, not just the Treasury market -- so they weren’t as visible. But the total flows were huge, as they had to be to support a large US trade deficit.

That was a world where the US structurally relied on a small set of other governments for large amounts of ongoing financing. A smaller external deficit means a bit less reliance on external financing. And maintaining the improvement that was brought about by the crisis requires more "balanced and sustainable" growth going forward.

Note: all data on official and Chinese inflows comes from the TIC, but the monthly TIC data has been adjusted to reflect the survey revisions -- i.e. flows have been reattributed from private investors in the UK and Hong Kong to China and official investors in proportion to the survey revisions. There is no survey data after June 2008, so I have estimated the magnitude of the likely revisions based on past patterns, and a bit of judgment. Given how much time I have spent looking at this data, I hope I get a bit of latitude here. If I used the 2008 revisions to estimate the 2009 revisions, China’s current holdings would be revised down slightly. I believe though that the flows that China accounts for a higher share of the UK flow now than in 2008 - and thus the 2006 and 2007 revisions provide a better guide to the likely 2009 revisions.

* The indirect bid at today’s two year auction was on the weak side, but there is a host of anecdotal evidence indicating ongoing central bank interest in short-dated notes as a higher-yielding alternative to bills. Central banks’ interest in the last two-year auction, for example, was especially strong.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store