Early Postwar Attitudes on Constitutional Revision

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Sheila A. SmithJohn E. Merow Senior Fellow for Asia-Pacific Studies

By Sheila A. SmithJohn E. Merow Senior Fellow for Asia-Pacific Studies

By

- Ayumi TeraokaResearch Associate, Japan Studies

This blog post is co-authored with Ayumi Teraoka, research associate for Japan studies at the Council on Foreign Relations and is part of a series entitled Will the Japanese Change Their Constitution?, in which leading experts discuss the prospects for revising Japan’s postwar constitution.

For many outside Japan, the growing interest in revising Japan’s constitution seems shocking, and often it is associated with a rightist push to rewrite Article Nine. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s advocacy in the past only reaffirms this impression. But this conversation about the origins of the document, about its suitability to Japanese values, and even about whether it can reflect the needs of a changing Japanese society began in the early postwar years.

Much has changed since Japan emerged again as a sovereign nation in 1952, and certainly the political climate of those early postwar years when the economy was in tatters and political control was fiercely contested by a host of parties from progressive left to conservative right. Japan’s conservatives, many with deep personal antagonisms, merged in one party, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), that would go on to dominant politics and govern Japan until the early-1990s. The Cold War was in full swing, with repeated crises across the Taiwan Straits, a China in the throes of socialist transformation, and a Korean peninsula cut in two with armies confronting each other across a Demilitarized Zone.

Japan’s democratic reforms were now being tested by poverty and economic instability, and a strengthened parliamentary system. The 1947 Constitution still defined this new postwar era and was used to legitimate social and economic reforms as well as political transformation. Japan’s left and right saw it differently; for many on the left, it protected them from a slide back into militarism, and for many on the right, it remained as evidence of the subjugation of their country in defeat. The newly formed LDP initiated renegotiation to revise the security treaty with the United States in 1957, and by the early 1960s, after deep social unrest over this new treaty signed in 1960, focused the country on the national task of economic growth and development. The polls presented here represented this transition from upheaval and political contest to the decade of “double-income” growth that created the foundations of today’s Japan.

A look back at some of these defining debates over the Japanese constitution in the 1950s helps put today’s conversation in context. The LDP government asked their citizens what they thought about their new constitution. Four findings from these surveys by the cabinet office offer insights on the current debate over constitutional revision.

Finding #1: When asked whether they supported revision, the Japanese were divided. About 40 percent of respondents wanted to participate in a discussion over revision, if needed, rather than allow their government simply to reinterpret their constitution. In other words, some Japanese people wanted to be asked. Another 44 percent, however, responded that they really did not think about the issue at all.

Opinion was consistently divided on whether to revise the constitution, but the balance of those “for revision” and those “against revision” shifted back and forth over the years.

For the first three years from 1955-1957, the cabinet polls simply asked whether respondents supported revision. As many people opted to revise as those who opted against it. By 1957, those for revision began to outnumber slightly those against.

From 1961-63, in response to the same question, the surveys gave respondents a more nuanced set of answers from which to choose: 1) Revise because of inappropriate content, 2) Revise because of how it was drafted, 3) Protect the current constitution because of its content, 4) Protect the current constitution because of current politics, and 5) I don’t know. Responses were scattered across four revise or protect choices (with a slight margin in favor of answer 2), but 30 percent opted for “I don’t know.”

Despite these divisions over whether revisions were necessary, there were signs that most Japanese wanted to debate the issue.

In the 1958, 1959, 1960, and 1965 surveys, respondents were offered the additional choice of debating whether to revise. In each of these years, around 40 percent selected that option, suggesting a desire for serious deliberation of the pros and cons of revision.

When asked how to fix flaws in the 1947 document, more respondents opted to revise than to simply reinterpret the constitution.

In the later years, the cabinet asked about how to fix possible flaws in the constitution. Again, the aim seems to be to test the waters on whether Japanese citizens would want to revise the document or simply allow the government to supplement its meaning through implementing changes. While 16 to 19 percent said the Japanese constitution should be kept intact without amendment, considerably more (31-36 percent) answered that it should be revised rather than implementing changes that were inconsistent.

Finding #2: Over time, the idea that the document was “MacArthur’s Constitution” seemed less relevant.

The cabinet office repeatedly asked about the origins of the constitution —who drafted it and whether it was forced upon the Japanese—and whether the process mattered to how the Japanese felt about it.

Yet there were significant changes in how the Japanese government phrased this question. Gradually, the government moved away from identifying the constitution as “MacArthur’s” or as a “U.S.-made” document.

One of the few consistent questions asked by the cabinet surveys was how Japan’s citizens thought about the origins of the 1947 constitution. In 1955, the poll asked if the current constitution is something “forced upon us by [Douglas] MacArthur,” directly mentioning the name of the Supreme Commander of Allied Powers (SCAP). In 1956-1957, the survey replaced MacArthur with “the United States.” In 1955, twice as many respondents selected “yes” than “no”, but in 1958-1959, the “yes” and “no” answers were almost equal, suggesting close association most Japanese have between MacArthur and their constitution.

From 1960-1965, the surveys again changed their language on the origins of the constitution. The cabinet no longer used the phrase “forced upon us by” Americans, and instead asked if the document was drafted mainly by the Americans or the Japanese. From 1960-64, respondents overwhelmingly chose “mainly the United States” over “mainly Japan.” But interestingly, in 1965, this margin declined.

While these early polls show that more Japanese thought that the Americans imposed the 1947 constitution on their country, there was a gradual shift in attitudes about the origins of the document over time. By the mid-1960s, respondents suggested that the origins of the document no longer seemed to matter as much.

In 1956-1957, this origin factor was one of the top reasons cited for revising the constitution. Yet a decade later, from 1966-1968, surveys asked if the constitution’s occupation origins were a significant flaw of the constitution or they could be dismissed. More responded that they could dismiss this aspect of their constitution, and we get a sense that the public is beginning to move on from the war’s legacies.

Finding #3: The Japanese public is divided on questions related to Article Nine. While hesitant to embrace revision, there are differences in opinions over what kind of military capability Japan might need in the new international politics of the Cold War.

Article Nine was treated gingerly by cabinet surveys in the early postwar years.

In most surveys, the cabinet did not directly mention Article Nine. Instead, they asked about whether Japanese thought there was a need for revising “the provision that forbids the possession of military forces (guntai)” or to “explicitly recognize the right of self-defense (jiei no tame no kenri) and the right to possess military forces to defend ourselves.” The political climate at the time was deeply contentious over Japan’s postwar Self Defense Force, created in 1954, with opposition parties and many civil society groups deeply convinced that this force was unconstitutional.

By the mid-1960s, cabinet questions shift from asking about revision to asking about reinterpreting the constitution.

From 1967-1968, the cabinet surveys asked about respondents’ views on how to interpret Article Nine, and in particular, they asked if the Japanese thought the article denies Japan the right to defend itself. A little over a decade after the SDF was established, only 35-42 percent of respondents thought that Japan had the right to exercise self-defense while approximately 30 percent thought it did not. 27-34 percent did not know how to answer that question.

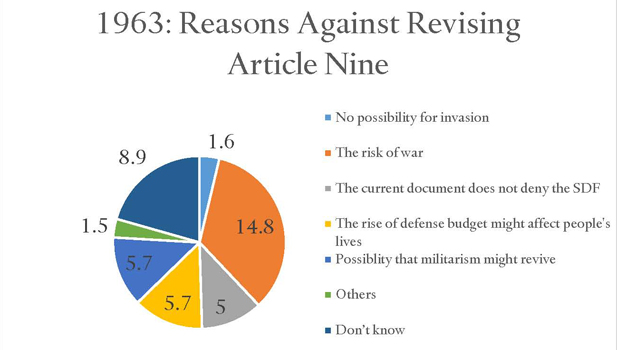

More people were against revising Article Nine, and the top reason cited is the risk of war.

Respondents were consistently divided over revising Article Nine. This could correlate with the tense domestic politics surrounding revision of the U.S.-Japan security treaty in the late 1950s.

Only in the 1962 and 1963 polls were respondents given the opportunity to say why they opposed revision of Article Nine. The most popular answer, as shown in the pie chart below, was the risk of being entrapped in a war, suggesting that regional tensions in Northeast Asia at that time led to less enthusiasm for rearmament rather than the impulse to arm.

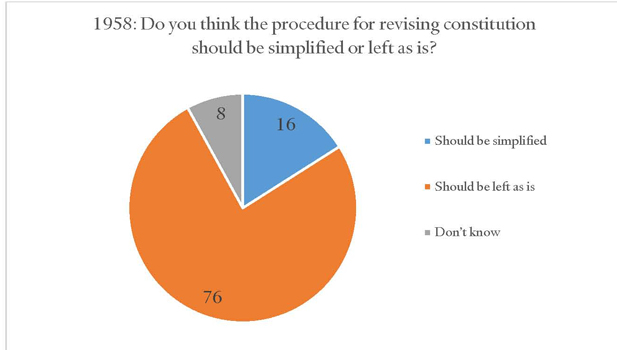

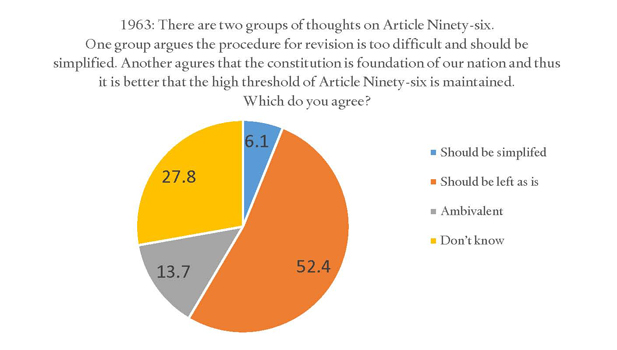

Finding #4: Despite the uneasy sentiments about the occupation roots of their new constitution, the Japanese did not want to make constitutional revision easier.

From 1956, the cabinet wanted to see what the Japanese thought about Article Ninety-six, the article that outlines the complex and difficult process for revision. The phrasing of the questions suggested that the revision process was too complicated, and asked what respondents thought.

Most polls first asked if respondents understood how Japan’s constitution could be revised. 30-40 percent of respondents were at least partially familiar with the procedures for revision. The surveys asked if respondents were aware of the Diet role and then asked about their familiarity with a national referendum. No results to these detailed questions are provided, however. Overall, roughly 20-25 percent of respondents claimed they understood that a two-thirds majority in both houses of the Diet was required as well as a national referendum.

Cabinet interest in this question of whether to simplify the revision process ended rather abruptly in 1963. But during the years from 1958-1963, it seems the idea of not touching article Ninety-six lost some ground. Nonetheless, 52 percent opposed making revision easier.

Second in a three part series on Japanese public opinion on Constitutional revision.