Emerging Asia: generally still intervening

More on:

Justin Lahart’s column today noted – quite correctly – that a slew of emerging Asian economies have allowed their exchange rates to appreciate against the dollar this year.

The verb “allow” is important. Their central banks previously had been intervening to defend a given exchange rate – so in effect, appreciation means that the central bank decided to stop actively holding the value of its currency down.

India is the best example. It intervened massively in February, but then scaled back its intervention and let the rupee appreciate. It is now taking heat for a “strong rupee.” And after several weeks without intervention, the RBI seems to have stepped back into the market two weeks ago (reserves went up).

Other central banks though never really stopped intervening. They just stopped defending a specific level. Asian reserve growth outside China has been quite strong this year. Malaysia is still intervening – look at its reserves (click on the chart option if you follow the link). Bank Negara Malaysia’s non-reserve foreign currency assets also seem to rising – if anyone knows what is going there, do tell!

Korea has – over the past few years – allowed the won to appreciate significantly. But it has gotten worried that a "strong won" risks becoming a "too-strong won." It seems to be intervening in the markets again. The May increase in Korea’s reserves is higher than can be explained by the interest income on Korea’s $250b.

Thailand let the baht appreciate in 2006. And then it got scared by the baht’s strength and imposed capital controls. That hurt the baht for a while, but only for a while. The central bank has been intervening again this year.

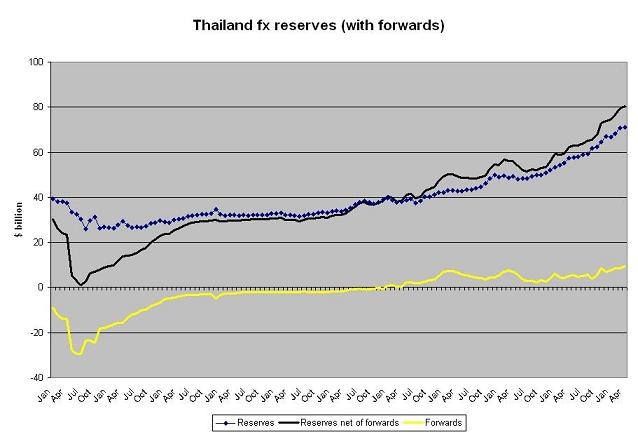

Look at the following chart. One legacy of Thailand’s crisis is that it reports both its actual foreign exchange reserves and the forward position of the central bank. I have summed up Thailand's cash reserves and its forward purchases (you can debate whether this is the right measure, or whether the forward position should be marked to market, but that is another issue). Thailand’s near bankruptcy in 1997 (the first year in the chart) shows up clearly, as does the ongoing increase its reserves now.

The basic dynamics of Asian reserve accumulation outside of China – at least in those countries with reasonable interest rates, as the low-rate, carry-trade funding currencies are a case apart – has been pretty clear. At various points in time, most Asian currencies have come under pressure to appreciate. The central bank usually initially resists the pressure. But sterilization is expensive (local interest rates are often higher than US rates), and eventually, the central bank gives in a bit, and lets the currency appreciate.

But then the currency rises a bit too much against the RMB, the country’s exporters get scared, they start to pressure the government, and sooner or later the central bank ends up intervening again.

That is one reason why China’s exchange rate policy isn’t just a matter of concern to the US and China. Many emerging countries are willing to let their currencies appreciate against the dollar. But they would rather not see their currencies appreciate against the RMB.

One of the strongest conclusions that emerged from the Peterson institute/ Bruegel/ KIIEP conference is that there is a huge difference for most countries between appreciating against the dollar together with other regional currencies and appreciating against the dollar when other regional currencies don’t move. European countries trade extensively among themselves. So long as all European currencies appreciate together against the dollar, a big move in the dollar v Europe need not imply a big change in the overall real exchange rates of most European countries. The same is true of Asia.

That is why I would suggest renaming Lahart’s column – how China can help the rest of Asia ease their grip …

There is another issue – one that I discussed at a recent hearing of the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission. China’s new state foreign exchange investment company supposedly wants to join Chinese firms and invest in emerging Asian equities. Such investment, though, implies additional capital inflows into these economies, and generally speaking, they all now receive larger inflows than they really want.

If say China wanted to invest in Thailand and the Thai central bank didn’t intervene, the baht would likely appreciate against the dollar, and against the RMB. If the Thais decided that they didn’t want the baht to appreciate, the Thai central bank would effectively end up buying the dollars China no longer wants.

I suspect that the Thai central bank would rather that the state foreign exchange investment company invest directly in the US!

If both China’s investment fund and the Gulf investment funds invest more in emerging Asia and if emerging Asian economies allow their currencies to appreciate and effectively use these inflows to finance a current account deficit not just more reserve growth, China would effectively start acting a bit like Japan acted in the early 1990s.

Back then Japan ran a current account surplus (saved more than it invested) and a large share of that surplus was invested – actually lent by Japanese banks – in emerging Asia. In the mid-90s, Japan’s surplus financed deficits elsewhere in Asia, not a deficit in the US.

China’s surplus now is so big though that there is no reason why it couldn’t finance large deficits elsewhere in Asia and help finance the United States large deficit at the same time. But it isn’t totally clear that the rest of Asia is any more comfortable with deficits financed by China’s state investment company – along with the Gulf investment funds -- than it is with deficits financed by private financiers.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store