How Ukraine’s Government Has Struggled to Adapt to Russia’s Digital Onslaught

Turf wars and the lack of coordination between Ukrainian government agencies has hindered the country’s response to a number of high-profile cyber incidents since 2015.

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Guest Blogger for Net Politics

Nadiya Kostyuk is a PhD candidate in political science and public policy at the University of Michigan. You can follow her @NadiyaKostyuk.

“When NATO meets with various cyber [organizations] in Ukraine, they only observe how these [organizations] fight with each other and blame each other for failures.” That’s how a Ukrainian expert described to me in 2015 his government’s inability to coordinate amongst itself and with other private sector to improve the country’s cybersecurity. It was a recurring theme that year when I conducted interviews in the country.

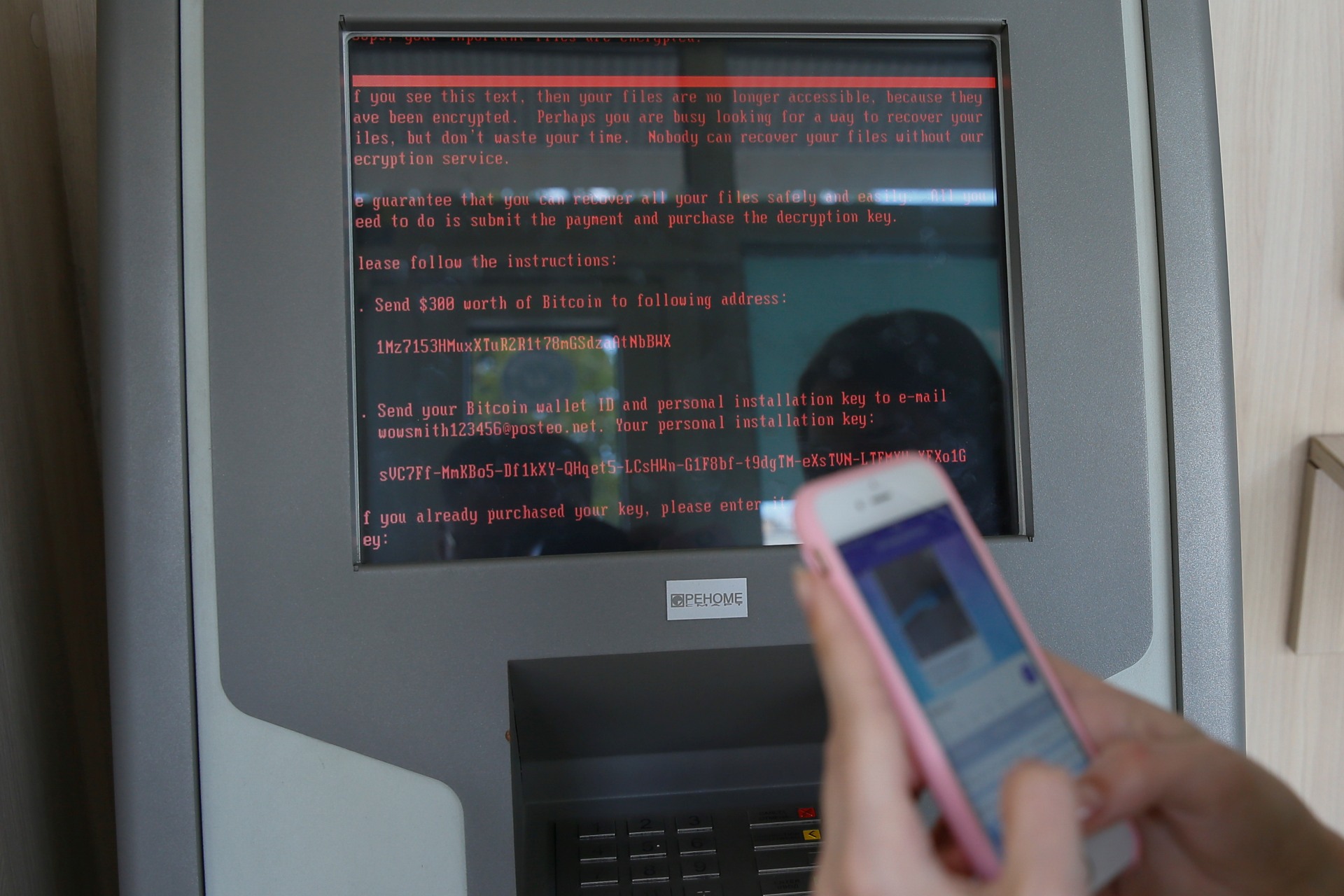

Last month, I went back to Ukraine and heard the same thing again. Why has this problem persisted, despite a drastic change in the country’s cyber threat landscape over the last three years? The country suffered two power disruptions in 2015 and 2016 and was plagued by the NotPetya ransomware attack last year. If these significant incidents can’t motivate state agencies to work together, what can?

In 2015, the Ukrainian government was only starting to develop a common cybersecurity lexicon. Kyiv’s main priority was repelling a Russian invasion in the east, not protecting the country from online threats. Intergovernmental cooperation was not seen as important. For example, the government applied a traditional external-internal division to cyber-enabled issues—the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which focuses on combatting cybercrime inside the country, did not feel the need to work with the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) whose priorities lie outside it.

The last three years have seen two significant changes on Ukraine’s cyber capacity front. First, the state beefed up its cyber apparatus by adding new responsibilities to existing organizations and by creating new cybersecurity units. For instance, the Minister of Defense became responsible for “repelling military aggression in cyberspace” and developed a new cyber unit with NATO assistance. Even the central bank became an important actor on the cybersecurity landscape, responsible for “establish[ing] requirements toward the cyber protection of critical information infrastructure in the banking sphere.” Second, Kyiv changed its perception of cybersecurity issues, and started addressing them in a multidisciplinary way. For example, the work of SBU began crossing the blurry external-internal divide and now works with the National Police to combat cybercrime, in addition to its traditional counterintelligence role.

However, these changes do not necessarily correlate with an improvement in the state’s efficiency. Konstiantyn Korsun, a director of Berezha Security, told me that the state of Ukrainian inter-agency cooperation resembled a 1814 Ukrainian fable in which three heroes are incapable of moving a loaded cart because each pulls it in different directions. Similarly, in Ukraine, each agency tasked with cybersecurity “attempts to grab whatever piece it can and pulls it in its own direction,” and, as a result, using the words from the fable, “their dealings come to naught and trouble is their labor’s only fruit.”

Instead, Korsun recommends having an agency responsible for coordinating cybersecurity efforts across the country. This agency should get the lion’s share of the government monies allocated to cybersecurity, which it can distribute as needed to relevant agencies, and should be responsible for the successes and failures of the entire state system devoted to cybersecurity.

Such an agency, in fact, exists in Ukraine. In 2016, the country set up its National Cybersecurity Center (NCC) within the Council of National Security and Defense. The center’s multi-agency representation—the chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, the SBU head, the interior minister, and the chief of the Defense Intelligence Directorate sit on its board—seemed to be the first step to success. But it is difficult to evaluate the center’s progress so far due to the lack of publicly available information on its progress as the NCC mostly deals with questions of national security. Tasked with a plethora of responsibilities, including assessing the country’s cybersecurity, identifying and detecting threats, and policy development, the NCC is seen as the entity that “diligently assign[s] responsibilities to others” (“razvodiashchiy”) according to Victor Zhora who runs a Ukranian cybersecurity company, but not as the main anchor for all cybersecurity efforts in the country.

Secrecy aside, will the NCC, in fact, be able to effectively juggle different and sometimes competing priorities of various agencies? Will it be able to stop bureaucratic fights over budgets, get rid of duplicative efforts, and take full responsibility for the failures and successes of the country’s cybersecurity?

These important questions are not unique to Ukraine as more and more nations build their cybersecurity apparatuses. Countries are in the process of identifying the best approaches to regulate digital security. This is accomplished by learning from their own mistakes or from those by their peers. Currently, it is unknown whether the NCC can make the state’s cybersecurity efforts more efficient and effective, but time will tell. Zhora sees the NCC playing a symbolic role until the state better educates members of parliament on cybersecurity, since only they can implement the cybersecurity laws and regulations that the country so desperately needs. Until then, the NCC will remain a razvodiashchiy agency, not Ukraine’s cybersecurity anchor.