Japan-South Korea Relations and the Biden Factor

President-Elect Biden and his team come at a critical time for Japan-South Korea relations.

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Guest Blogger for Asia Unbound

Yasuyo Sakata is a professor at Kanda University of International Studies in Japan.

The Downward Spiral

President-Elect Biden and his team come at a critical time for Japan-South Korea relations. In the past two years, the Japan-South Korea relationship has experienced one of its lowest points since the normalization of relations in 1965.

It started with a Korean Supreme Court ruling in October 2018 regarding Korean wartime laborers during the Japanese colonial era which called for Japanese companies to pay compensation to the victims. This triggered a contentious political-legal battle. The Japanese government sees it as a challenge to the 1965 Normalization Treaty and the Settlement of Claims agreement, which is deemed as the foundation for postwar Japan-South Korea relations. The South Korean government is stuck between a rock and a hard place if it is to respect the Supreme Court ruling and the 1965 agreement.

The diplomatic impasse then spilled over into economy and security. The Japanese Cabinet’s sudden decision in summer 2019 to tighten export control measures and delist South Korea from its so-called “white list” of preferred trading partners hit South Korea’s competitive semiconductor industry. This led to countermeasures by South Korea’s presidential Blue House, which brought the quarrel to the World Trade Organization (WTO). In a final blow, the Blue House threatened to terminate the bilateral Japan-South Korea military intelligence sharing agreement unless Japan rescinded its export control measures.

Termination of the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) could have triggered the unraveling of trilateral U.S.-Japan-South Korea security cooperation. The Trump administration strongly intervened to call on its allies to stop the vicious cycle of linkage politics and in December 2019, Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and South Korean President Moon Jae-in met in Chengdu, China at the China-Japan-Korea trilateral summit. In a subsequent speech to the Japanese Diet, Abe called South Korea (also known as the Republic of Korea, or ROK) “our most important neighbor, which shares fundamental values and strategic interests with Japan” while continuing to ask South Korea to adhere to the 1965 agreement.

New Momentum?

In September 2020, former Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga became Japan’s prime minister following Abe’s resignation. Suga’s priority is the domestic agenda: the COVID-19 pandemic and the economy, digitalization reform, and the 2021 Tokyo Olympics. On the foreign policy front, Suga will follow in Abe’s footsteps, promoting a strong U.S.-Japan alliance, a shared vision for the Indo-Pacific, and global strategic cooperation on the China challenge.

On the Korean laborers issue, Suga will continue to call for compliance with the 1965 agreement, but his reputation as a politician known to “get things done” indicates that he may be more pragmatic than his predecessor. But Moon’s unilateral scrapping of the so-called “comfort women agreement” in 2018, which Suga played a significant role in reaching as Abe’s Cabinet Secretary, has made Suga very cautious. Still, Suga sees people-to-people exchange and tourism as beneficial to Japanese economic recovery following COVID-19. So Suga will remain tough, but he will also be inclined to pursue dialogue with South Korea to see if a realistic solution can be reached.

In his first telephone conversation with Moon, Suga described Japan and South Korea as “extremely important neighbors” and said “we cannot allow our relations to remain as they are,” signaling his intent to mend relations. After months of impasse due to COVID-19, Takeo Kawamura, head of the Japan-Korea Parliamentarians’ Union, met informally with his counterparts in Seoul in October 2020. Senior working-level talks resumed, and later that month, Ministry of Foreign Affairs director-level talks took place in Seoul to address wartime laborers and other issues.

A second source of momentum for Japan-Korea relations came in November with former Vice President Joe Biden’s victory in the U.S. presidential election. Biden and his team’s message of rebuilding alliances and partnerships strongly resonated in Asia. Suga and Moon quickly embraced the election results and congratulated Biden for his win.

Following Biden’s election, South Korea made multi-pronged overtures to Japan. Park Jie-won, head of the National Intelligence Service, traveled to Tokyo on November 9 as a presidential envoy. In mid-November, a seven-member delegation from the Korea-Japan Parliamentarians’ Union headed by Kim Jin-pyo of the ruling Democratic Party met with Suga and parliamentarian counterparts in Tokyo and agreed to establish cooperation committees on the Tokyo Olympics, COVID-19 pandemic response, and sports and cultural exchange. On November 23, the Blue House appointed Representative Kang Chan-gil, former chairman of the Korea-Japan Parliamentarians’ Union, as the next ambassador to Japan.

In the meantime, cultural, social, and business ties continue to grow. Japanese viewers have binged on K-dramas on Netflix during the COVID-19 pandemic. Niziu, a JK-Pop girl group produced by JYP Entertainment and SONY debut this year. South Korean boycotts of Japanese goods since last summer’s export control measures seem to be winding down, with customers returning to UNIQLO and Toyota Lexus.

Despite these improvements, the two sides still do not see eye-to-eye on the laborers issue. If liquidation of Japanese company assets occurs, the Japanese government has said it will take further retaliatory measures. Suga has called on South Korea to prevent liquidation of the assets, but the clock is ticking.

The Way Forward

Leadership changes in Japan and the United States are providing a new source of momentum. But whether this progress will bear fruit depends firstly on Japan and South Korea, and then on their ally, the United States. As long as Japan and Korea remain preoccupied by bilateral issues, it will be politically difficult to strengthen necessary strategic and security cooperation.

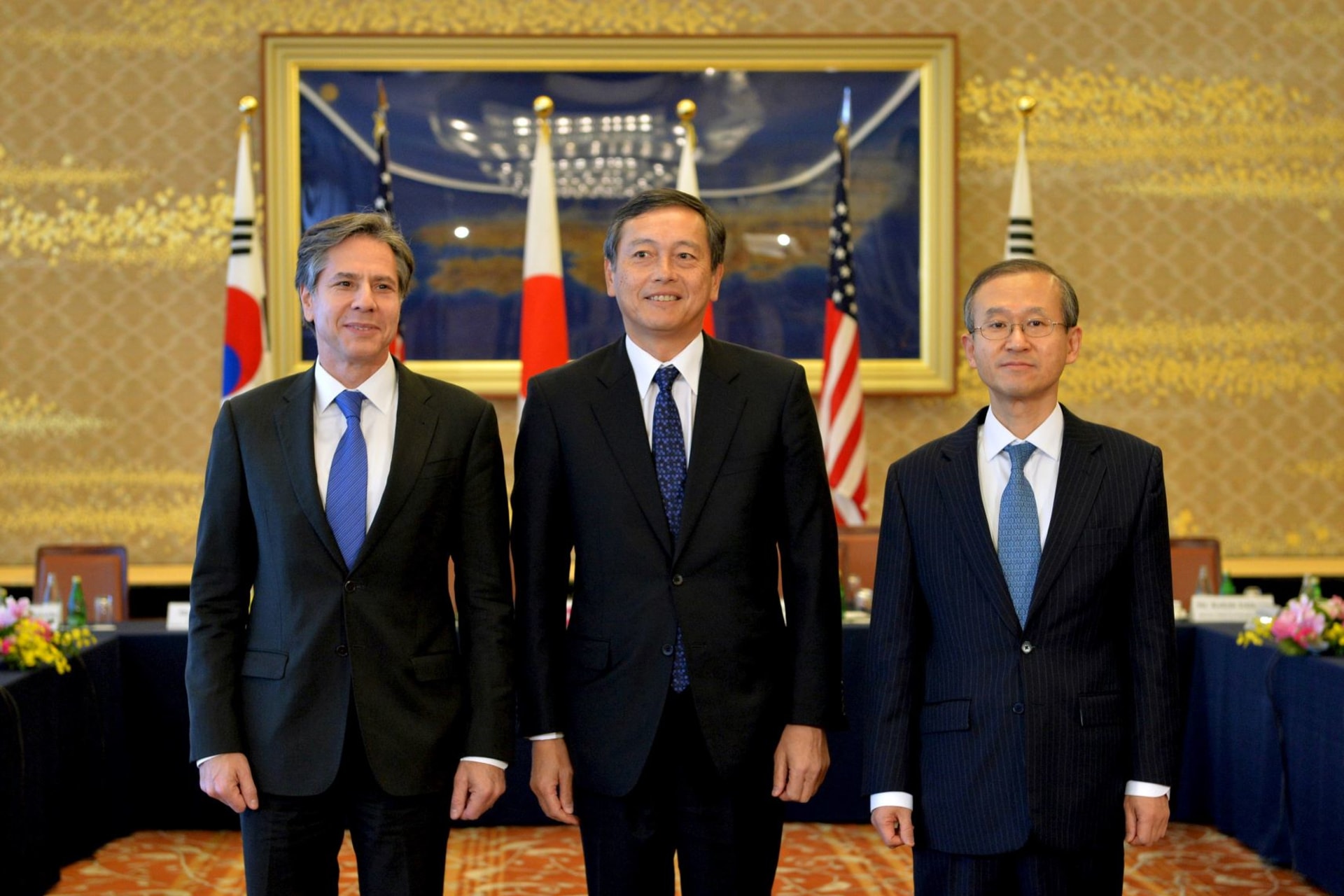

It is, therefore, in the national interest of the United States to prod its allies to reset relations and promote strategic cooperation. The Biden team has sent a clear message that it will be vigilant on Japan-South Korea relations and will work to restore both inter-alliance cooperation and the U.S.-Japan-ROK trilateral cooperation. So, how can the United States help get Japan-South Korea relations back on track?

1. The United States should play an assertive role in reinstating common values and bringing the two allies into strategic alignment. The new Biden administration should promote consensus and unity toward a common strategic direction to maintain democracy, shared values, and a rules-based international order.

2. The United States should leave the resolution of bilateral issues – including Korean laborers and export control – to its allies and avoid any overt intervention, as its participation in negotiations over the 2015 comfort women agreement has unfortunately colored perceptions of U.S. involvement. However, the United States should be conscious about the management of Japan-Korea relations and support the so-called “two track” approach that separates history issues from other issues and encourage Japan and South Korea to work toward a resolution.

3. The United States should re-strengthen U.S.-Japan and U.S.-ROK alliance security and alliance management. Defense cost-sharing issues should be solved and stabilized. Regional burden-sharing, multilateral exercises, prevention of incidents at air and sea (to prevent incidents like those in December 2018 between the Japan and ROK navies) , and efforts to address intrusions into the East Asia Air Defense Identification Zone should also be addressed. The allies should reinvigorate institutionalization of trilateral cooperation at diplomatic and defense levels to protect their partnership from undue political interference.

4. The United States should re-strengthen U.S.-Japan-ROK trilateral cooperation on North Korea in the following areas: (1) deterrence and defense vis-a-vis the North Korea nuclear, missile and cyber threat, intelligence cooperation (including the reaffirmation of GSOMIA), and joint exercises; (2) non-proliferation and denuclearization of North Korea. Any progress in the U.S.-North Korea negotiations should be supported by U.S.-Japan-ROK trilateral coordination mechanisms that include sanctions, diplomatic negotiations, and the denuclearization process on the agenda.

5. The United States should promote and fine-tune strategic alignment on China policy in the context of the Indo-Pacific region. The United States and Japan already share a vision for the Indo-Pacific, and the United States has linked its own strategy with South Korea’s New Southern Policy. Japan-South Korea cooperation is the missing link.

In the next phase of the Indo-Pacific strategy, alignment on the economic dimension, , especially economic security in digital and sensitive technology is essential. The export control row between Japan and South Korea has become an obstacle to strategic economic dialogue and cooperation. The United States should build an environment through economic dialogues that encourages Japan and South Korea to overcome the export control issue. Considering the possibility of accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) enhancement of bilateral economic agreements should also be on the agenda.

6. Beyond Northeast Asia and the Indo-Pacific, the partners should jointly pursue global cooperation on COVID-19 and health security (World Health Organization reform), climate change and renewable energy, WTO reform, digital economy, and rule-making.

The U.S.-Japan and U.S.-ROK bilateral alliances, along with U.S.-Japan-ROK trilateral cooperation, are the anchor in Northeast Asia security and should be so beyond. But the downturn in Japan-South Korea diplomatic relations has weakened inter-alliance cooperation. The Biden administration can play a critical role at this juncture to restore Japan-South Korea strategic cooperation.