By experts and staff

- Published

In 2010, then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton uttered a few simple words that, looking back on it, previewed aspects of Washington’s coming China policy. Previous U.S. administrations dating back to that of Richard Nixon had worked closely with China, with some believing that the country’s economic rise would foster democracy internally and, in turn, truly cooperative relations between Beijing and Washington. But Secretary Clinton and then-President Barack Obama had at least begun to realize, if somewhat belatedly, that China was rising to become not a collaborator in the international order, but a competitor—and one that threatened to undermine the U.S.-led liberal international order, particularly in Asia.

So, while in Hanoi for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Regional Forum in 2010, Clinton took a stance. She declared, in contrast to Washington’s previous “hands-off” approach, that the peaceful resolution of competing sovereignty claims to the South China Sea—between China, Taiwan, and several Southeast Asian countries—was a U.S. “national interest.” Beijing responded accordingly. Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi called her comments “an attack on China,” which was no surprise, since China claims just about the entire sea as its own. Yang also cemented the fears of the United States and many Southeast Asian states by telling his Southeast Asian counterparts that “China is a big country and you are small countries and that is a fact” —comments that many say motivated Obama’s admittedly lackluster but nonetheless militarily-relevant pivot to Asia.

This rhetorical battle forecasted the coming era of disorder. Indeed, Beijing and Washington have since strived for preeminence in the Indo-Pacific—with China having secured economic dominance while the United States retains its security strength—all while governments from South to Southeast Asia and everywhere in between find themselves caught in the middle. This is the thesis advanced by the contributors to New Asian Disorder: Rivalries Embroiling the Pacific Century, an uneven volume edited by Lowell Dittmer, a professor emeritus of political science at the University of California, Berkeley.

Some of these chapters trod familiar territory. Ho-fung Hung’s essay, “China in the Rise and Fall of the ‘New World Order,’” is an example. The author, the Henry M. and Elizabeth P. Wiesenfeld Professor in Political Economy at Johns Hopkins University, does an admirable job of tracing the steady decline of U.S. hegemony in Asia, but he ends up restating what is clearly a fact: that U.S. economic influence has declined in Asia, while China’s own such influence has grown.

Another such example is “Bringing the Strategic Triangle Back,” an essay by Yu-Shan Wu, a NIHSS Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Pretoria, in South Africa. Her chapter is largely descriptive rather than analytical, offering an interesting but not particularly novel look at what she calls “small and medium countries” responses’ to the ongoing U.S.-China rivalry. Her focus on Taiwan and South Korea is a bit odd, too, as neither one of them—particularly not South Korea—is small or medium in economic or geopolitical terms. These selections are odd also because she leaves small and medium (and developing) countries, like those in South and Southeast Asia, undiscussed.

Lowell Dittmer’s chapter, “Southeast Asia among the Powers,” actually focuses on Southeast Asia, of course, but Dittmer simplifies the region a bit too much. He declares, correctly, that Southeast Asian countries are largely “hedging” between the United States and China as the risk of confrontation between the two rises. But he oddly attributes Southeast Asian hesitancy about China seemingly only to Beijing’s aggressive behavior in the South China Sea, suggesting that if China and ASEAN reached a “compromise” on these territorial claims, “then ASEAN no longer needs its hedges and can drift further into China’s orbit, where its economic future seems to lie.”

This is far too simplistic. ASEAN’s concern about China is not only about the South China Sea; it is more complicated, and goes much deeper. Would, for instance, Vietnam or the Philippines happily align with China if Hanoi, Manila, and Beijing settled their respective South China Sea disputes? Almost surely not, given the salience of anti-Chinese sentiment among these countries’ publics. Indeed, Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte’s pro-China line has prompted protests throughout the country, while some of the candidates running to replace him have shied away from his policy. And would Singapore, a perpetual hedger, feel comfortable losing its U.S. security assistance to align with China? Again, almost surely not.

Nonetheless, there are a few standout essays in this collection.

One such example is the contribution of National Taiwan University political science professor Yun-han Chu, Shandong University professor of political science and public administration Hsin-Che Wu, and National Taiwan University political science professor Min-Hua Huang.

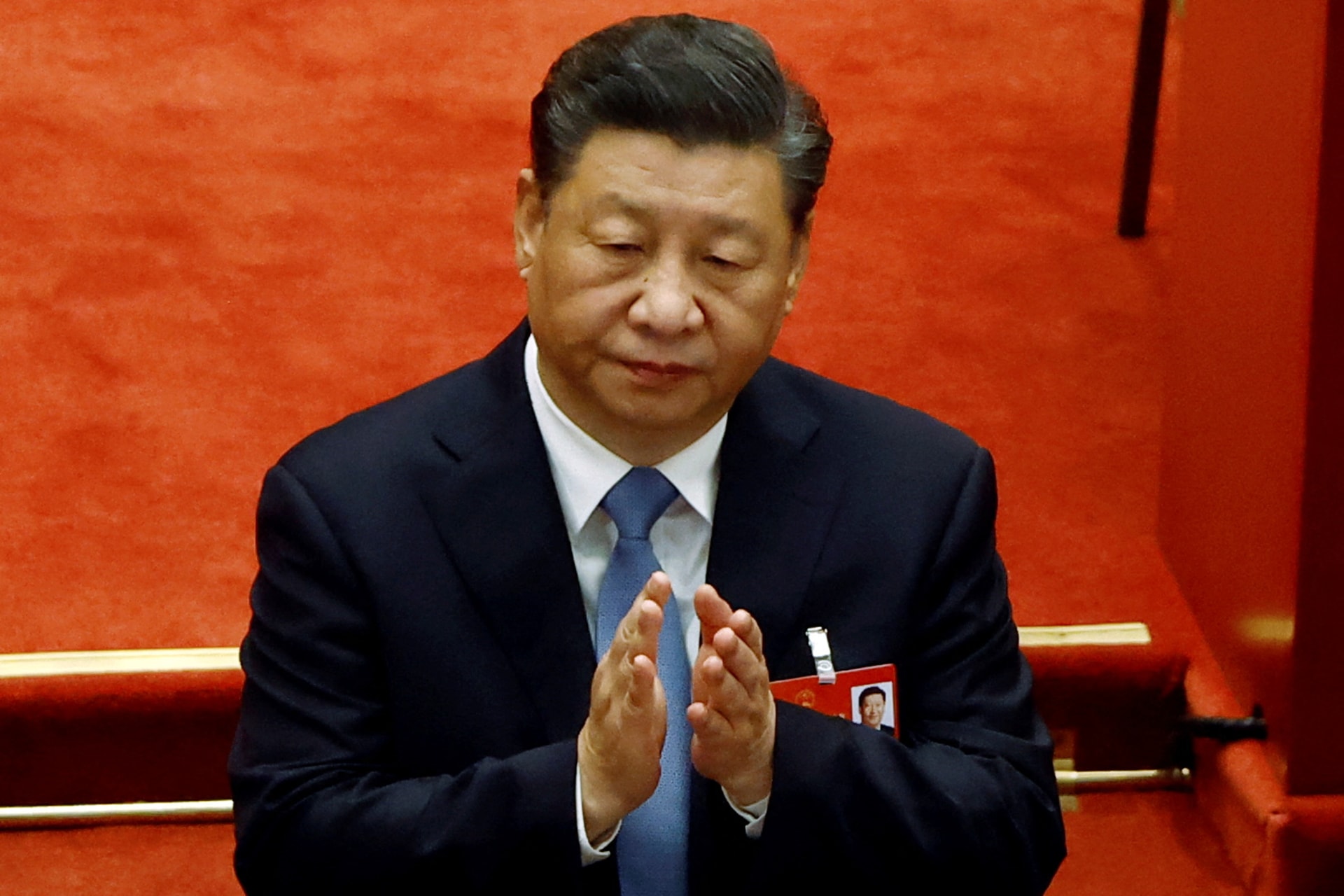

Their collaborative essay, “Assessing China’s Public Diplomacy under the Leadership of Xi Jinping in Asia,” relies on data from the Asian Barometer Survey—which regularly surveys people in Cambodia, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Mongolia, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam—to present a compelling statistical analysis that examines who in Asia supports or dislikes China, and why.

They found that across the board, people in countries that maintain territorial disputes with China, such as Japan and Vietnam, have more negative views of China’s influence than those in countries without such claims. They found also, interestingly, that political interest is positively associated with favorable perceptions of China—implying that those who engage more with the media, and read more about China, have more positive views of the country. They found, too, that people perceive China more positively when the economic dimension of globalization is stressed, but more negatively if the social dimension is stressed. Additionally, those who are satisfied with their household income are generally more likely to view China’s influence positively. Perhaps most strikingly, they found that while China has been more aggressive under President Xi Jinping’s leadership, China’s favorability has largely not fallen during this period.

Their three main conclusions are compelling, too: (1) people in Asia have more positive views of China if they believe China to be more democratic than the United States; (2) people with positive views of democracy have less positive views of China; and (3) people who think China will be the most influential country in the future or believe China to be a model for development have more favorable views of the country. This essay stands out, then, for offering new, tangible insights that both policymakers and scholars alike will find hugely helpful moving forward.

Perhaps the best essay, “The Coming of the Economic Warring States,” comes from Guoguang Wu, a professor of political science at the University of Victoria, Canada. In this chapter, he compares the current U.S.-China rivalry to the ancient Chinese Warring States period, demonstrating how two strategies have dominated both eras: hezong (building a multilateral coalition against the rising threat) or lianheng (engaging in bilateral ties with the rising power).

Of course, these two eras are not identical, as the author makes clear, but there are compelling comparisons. The United States today identifies China as a rising threat, just as the ancient hegemon, the Qi, identified the Qin. And while the United States is now trying to challenge this “threat,” it has struggled to offer a compelling hezong strategy, primarily because—thanks to domestic politics—Washington has not offered Asian countries meaningful economic benefits. China, of course, has done and continues to do just that.

Leaning on history, the author thus offers a troubling lesson to the United States. “In the ancient case,” he writes, “the [Qi-led] hezong strategy [...] eventually failed, because the lianheng strategy adopted by the Qin worked very well in attracting each of the six states […] primarily by providing benefits through bilateral connections, which also fostered the inclination toward appeasement among elites of the six states.” That should sound familiar: because the United States does not have a meaningful hezong strategy right now, particularly in terms of economics, it is at risk of losing overall preeminence in Asia to China, whose own lianheng efforts have found great purchase.

Nonetheless, China’s “victory” is unlikely to be complete, as several authors—including the editor, Dittmer—make clear. Instead, Asian countries are more likely to find themselves caught within the storm of U.S.-China competition that, while peaceful for now, is increasingly tense. “What is most likely,” Dittmer writes, “is that Sino-US rivalry remains, while much of the rest of Asia tries to profit from both sides for as long as possible without taking sides.”

This is correct, but as Dittmer leaves unstated, the painful reality is that Asian leaders do not truly hold the reins of their region’s future. Sure, they can seek benefits from Beijing and Washington for the foreseeable future, but if the two stumble into conflict—say, if China invades Taiwan—they will no longer be able to balance them. They will have to choose, as Japan and South Korea have found out regarding Russia in recent weeks. The cruel truth, then, is that Asia will have this disorded peace only if Washington and Beijing can keep it.