“Everything about recent experience,” Paul Krugman says, “suggests that the world desperately needs fiscal expansion to boost demand and … that our sole reliance on central banks isn’t working.”

As evidence, Krugman points to a positive relationship between government expenditure and economic growth over recent years: 2010-2013.

More on:

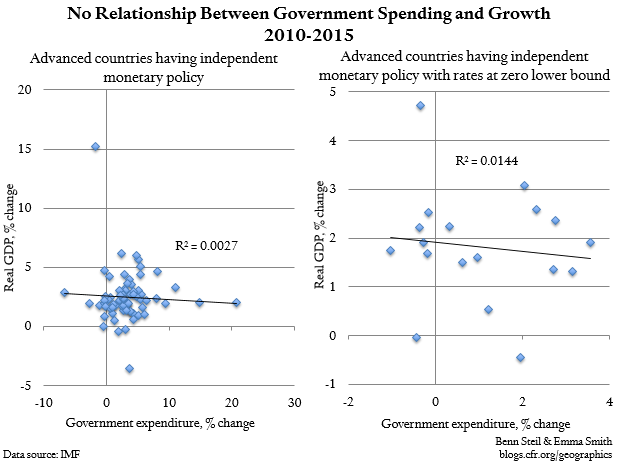

But we showed last January that this relationship did not, in fact, hold in those years for countries with independent monetary policy—that is, those outside the euro area. The logic, entirely conventional, is that central banks can (and do) act to offset the stimulative and contractionary influences of changes in fiscal policy. And as the figure above shows, Krugman’s posited relationship between government expenditure and growth still doesn’t hold, for countries with independent monetary policy, when the data are expanded out to 2015.

Krugman has in the past responded by arguing that everything is different at the zero lower bound (ZLB) for monetary policy, pointing to his work on so-called liquidity traps. And indeed he has invoked the ZLB in support of fiscal expansion in the U.S., the UK, and Japan. So what about these three?

As the right-hand figure above shows, there is no relationship between government expenditure and growth even for countries at the ZLB. (In fact, it is slightly negative.) Of course, all three of these countries used monetary policy tools aggressively between 2010 and 2015—even while at the ZLB.

In short, the “recent experience” Krugman refers to doesn’t actually back his case. Liquidity traps appear instead to have become a theoretical fig leaf for policies Krugman supports for other reasons.

More on: