Remembering the Vietnam “Coup Cable”

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

Things usually slow down in Washington in August. Congress goes into recess, and Washingtonians who can leave town do. But this predictable lull in government activity doesn’t mean that policymaking stops. Indeed, it can be precisely because much of official Washington is elsewhere that critical decisions get made. The cable that the U.S. State Department issued on August 24, 1963, is a classic example.

The target of the coup cable was Ngo Dinh Diem. He had once been an American favorite. The United States helped install him as South Vietnam’s leader after the 1954 Geneva Accords divided Vietnam in two. Washington looked the other way when he won 98.2 percent of the vote in a national referendum in October 1955, receiving 50 percent more votes in Saigon than there were registered voters. When Diem flew to Washington, DC, in May 1957, President Dwight Eisenhower personally met him at the airport, something Ike did for only one other head of state.

Eisenhower’s man in Saigon was initially John F. Kennedy’s as well. Kennedy’s vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson, called Diem the “Churchill of Asia” during a 1961 visit to South Vietnam. But relations with Diem soured as the Vietcong insurgency grew in size and urgency. By the end of 1962, Kennedy had dispatched roughly 11,000 U.S. military advisors to South Vietnam, where they trained South Vietnamese troops and frequently (but secretly) led them on operations against the Vietcong. Diem bristled at the growing American presence—and at U.S. officials telling him what to do. He complained, “All these soldiers I never asked to come here. They don’t even have passports.”

The Kennedy administration in turn worried that Diem’s increasingly heavy-handed suppression of his domestic critics was alienating the South Vietnamese public he was trying to lead. Diem came from a devout Catholic family—his older brother was the Catholic archbishop of the old imperial city of Hue—and he himself had taken a vow of chastity. The vast majority of Vietnamese, however, were Buddhists. They rankled at the blatant favoritism that Diem showed his fellow Catholics. As criticism of Diem grew, he relied more and more on his younger brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, his chief political advisor and the informal head of both South Vietnam’s Special Forces and its secret police, to harass and silence his critics.

Tensions spilled into public view in May 1963. On the Buddha’s 2,527th birthday, Nhu’s forces fired on Buddhists protesting the government’s ban on flying religious flags. Nine people were killed, including several children. More protests quickly followed. Then in June, an elderly monk set himself on fire in downtown Saigon. Seven other monks soon followed his example. Diem did nothing to stem the growing public anger, while his sister-in-law, Madame Nhu, added to it. She likened the self-immolations to a “barbecue.” “Let them burn,” she said, “and we shall clap our hands.” Despite promises from Diem that his government would not escalate the “Buddhist Crisis,” Nhu’s forces ransacked Buddhist pagodas across the country on August 21, arresting more than 1,400 people.

The raids were the last straw for three second-tier U.S. officials: Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs W. Averell Harriman, Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs Roger Hilsman, and National Security Council staff member Michael V. Forrestal. They were appalled by Nhu’s tactics and fearful that his anti-Americanism would lead him to strike a deal with communist North Vietnam. Acting on intelligence reports that some South Vietnamese generals might be willing to overthrow Diem, they set out make a coup official U.S. policy. With every one of the administration’s senior national security officials out of town, they drafted a cable on Saturday, August 24, to be sent to Henry Cabot Lodge, the U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam. (He had arrived in Saigon just two days earlier and wouldn’t present his diplomatic credentials to the South Vietnamese government until the next day.) The cable was clear: Lodge should encourage the South Vietnamese generals to oust Diem.

Forrestal didn’t ask his boss, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, or Secretary of State Dean Rusk or Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, to approve the cable. He instead called JFK directly. Kennedy, who was spending the weekend at his family’s compound in Hyannis Port, told Forrestal to get a senior administration official to okay the cable. Forrestal, Harriman, and Hilsman then used the impression that Kennedy had already approved the cable to secure the approval of Secretary Rusk and several other senior officials. After being told that his senior advisors had signed off on the cable, Kennedy approved it.

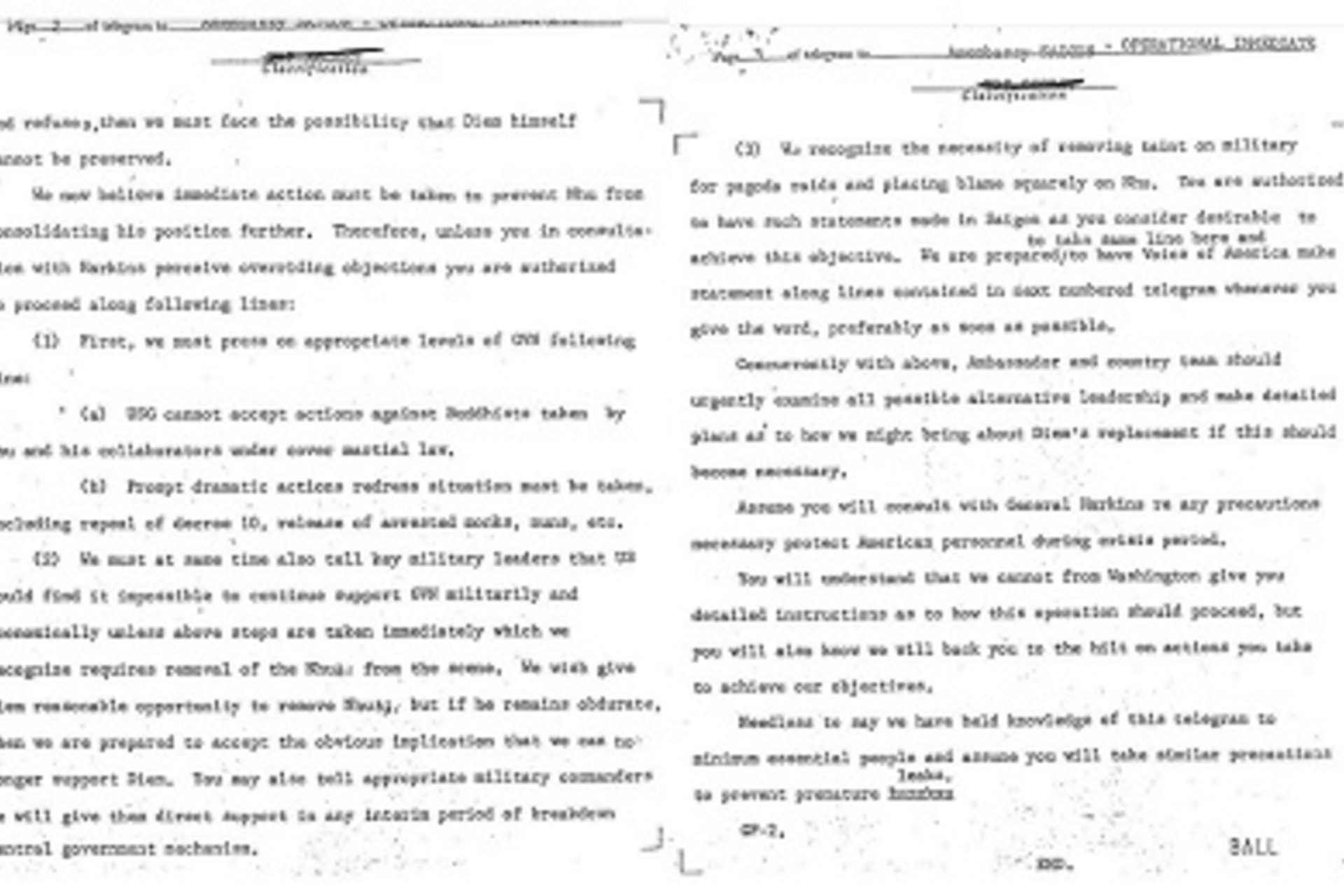

By nightfall, Cable 243 had gone out. It told Lodge:

U.S. Government cannot tolerate situation in which power lies in Nhu’s hands. Diem must be given chance to rid himself of Nhu and his coterie and replace them with the best military and political personalities available.

If in spite of all your efforts, Diem remains obdurate and refuses, then we must face the possibility that Diem himself cannot be preserved.

Ambassador and country team should urgently examine all possible alternative leadership and make detailed plans as to how we might bring about Diem’s replacement if this should become necessary.

You will understand that we cannot from Washington give you detailed instructions as to how this operation should proceed, but you will also know we will back you to the hilt on actions you take to achieve our objectives.

Tempers rose when Kennedy’s national security team reassembled at the White House the following Monday morning. McNamara, CIA Director John A. McCone, and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor all opposed the coup and objected to what Taylor later called an “egregious end run” around the normal decision-making process. Forrestal offered to resign, but Kennedy told him, “You’re not worth firing. You owe me something, so you stick around.” The acrimony among his advisors drove JFK to lament, “My God! My government is coming apart.” (Bundy later quipped that the lesson of Cable 243 was: “Never do business on the weekend.”) Yet when Kennedy asked his advisors whether he should retract the cable, none said yes.

While official Washington bickered over how the cable came to be, Lodge enthusiastically implemented his instructions. Within days, U.S. officials in Saigon had secretly contacted disaffected South Vietnamese generals. The message was direct: while the United States would not help the coup plotters overthrow Diem, it would recognize their new government. Suddenly, a coup seemed imminent. Then, just as quickly as it had come together, the coup plot fell apart. The plotters could not arrange for the right military units to be in Saigon, and they worried that that Washington might backtrack on its offer.

Despite the collapse of the initial plot, complaints about how Cable 243 was approved, and the doubts about the wisdom of encouraging a coup, Kennedy never reversed the decision he had made at Hyannis Port. He instead left the question of whether to pursue a coup in Lodge’s hands. That decision was tantamount to giving it a green light. Lodge firmly believed that the administration had already “launched on a course from which there is no respectable turn back.”

The coup that Kennedy authorized and Lodge helped orchestrate materialized on November 1, 1963. Although JFK had hoped that it would be bloodless, it wasn’t. Diem and his brother at first eluded the coup plotters. But they were eventually captured and then shot and stabbed repeatedly in the back of an armored car. The plotters initially claimed that the brothers had committed suicide. A photo of the murder scene, however, showed the blood-soaked bodies of both men with their hands tied behind their back. Time magazine ran the photo over the caption, “’Suicide’ with no hands.”

Many South Vietnamese cheered the end of Diem’s rule. However, the coup didn’t produce the stability and national unity that U.S. officials wanted. Vietnam would go through seven leadership changes in the following year-and-a-half. But that instability would bedevil a different president. Three weeks after Diem’s murder, Kennedy was assassinated.