TWE Remembers: The Assassination of Jean Jaurès

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

Yesterday’s post noted that the 1916 Black Tom explosion raises a great “what if” question: would Woodrow Wilson have lost his bid for re-election that fall if Americans had known that German saboteurs had blown up Black Tom? Here’s another “what if”: would World War I have followed a different course had Jean Jaurès, the leader of the French Socialist Party in the Chamber of Deputies, not been assassinated on July 31, 1914?

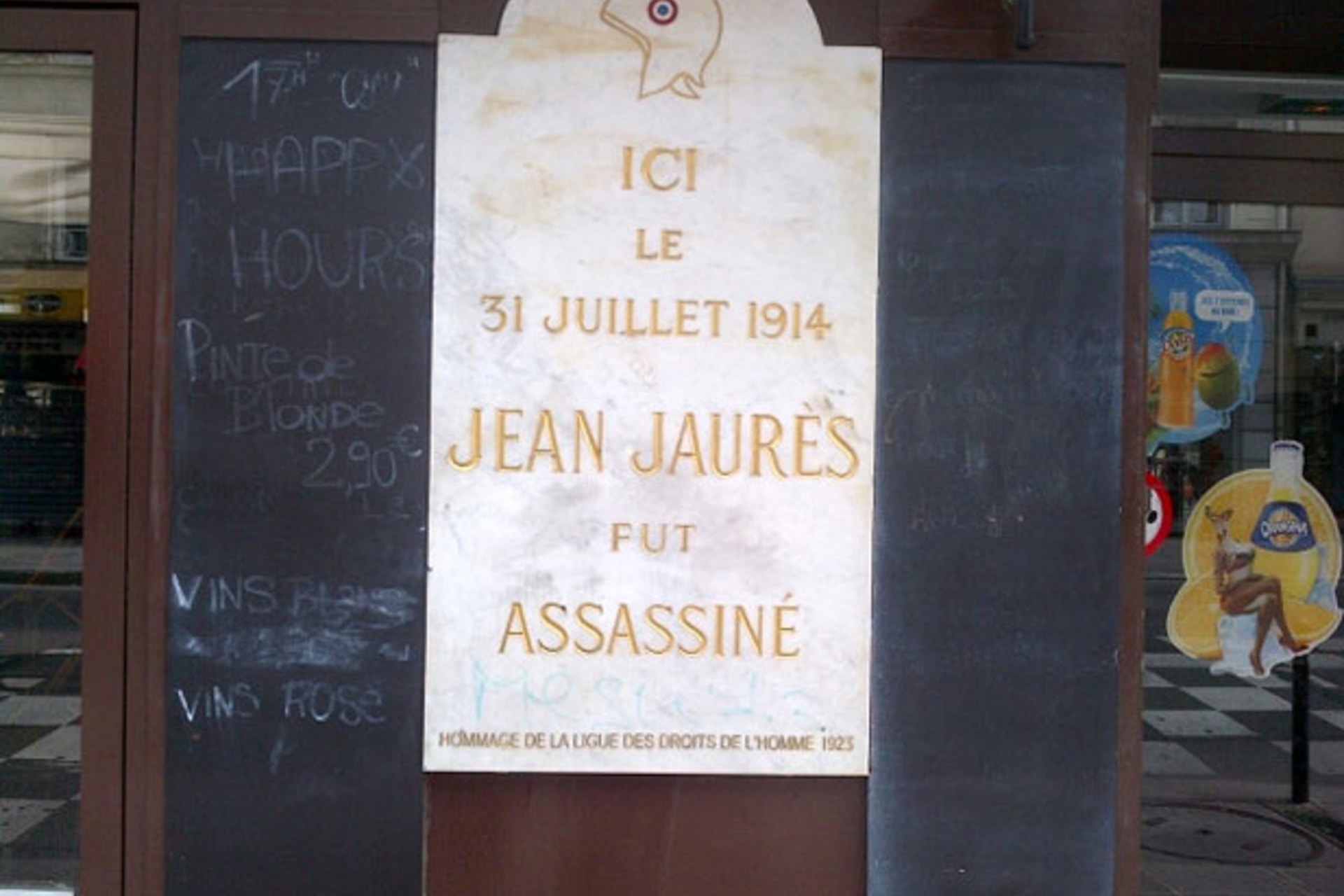

Jaurès was at the Café du Croissant that evening for a working dinner. He had much to do. He had been fighting for weeks to stop Europe’s march to war. Just after 9:30 p.m., Raoul Villain, a twenty-nine year-old right-wing French nationalist, fired two shots through the café’s open window. One shot missed. The other didn’t. Jaurès died almost immediately.

Jaurès was a towering figure in pre-World War I France, and he remains a political icon among French socialists to this day. One of his biographers described him this way:

Neither ministers nor deputies, even the most conservative among them, could afford to ignore Jaurès; more than any other Socialist in the parliaments of Europe, he was a moral and political force, hated by some, feared by more, but almost universally respected.

A co-founder of the socialist newspaper L’Humanité, Jaurès bitterly opposed war. He viewed it as “the horrible crime which forces into a quarrel brothers in work and in poverty all the world over.” In the wake of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28, he urged members of the French Socialist Party to work for a peaceful resolution of the “July Crisis.” On July 7, he urged the Chamber of Deputies to oppose a proposal to send France’s president and prime minister to St. Petersburg for consultations with the Tsar and warned of secret treaties between democratic France and authoritarian Russia:

We find it inadmissible that France should become involved in wild Balkan adventures because of treaties of which she knows neither the text, nor the sense, nor the limits, nor the consequences.

On July 25, the day that Austria rejected Serbia’s response to its ultimatum, Jaurès gave a speech warning his audience of what the rejection meant:

Citizens, the note which Austria has sent to Serbia is full of threats; and if Austria invades Slavic territory, if the Austrians attack the Serbs,…we can foresee Russia’s entry into the war; and if Russia intervenes, Austria, confronted by two enemies, will invoke her treaty of alliance with Germany; and Germany has informed the powers through her ambassadors that she will come to the aid of Austria… But then, it is not only the Austro-German Alliance which will come into play, but also the secret treaty between Russia and France…Think of what that disaster would mean for Europe…What a massacre, what destruction, what barbarism!

Four days later, he traveled to Brussels for a meeting of the International Socialist Bureau. There he urged German socialists to launch a general strike in opposition to the war. Jaurès hoped that worker opposition would compel European capitals to turn to diplomacy and away from war.

Not surprisingly, Jaurès’s opposition to war infuriated French nationalists driven by revanchism and hoping to reclaim the territory lost to Germany forty-four years earlier. They regarded Jaurès as a traitor. Villain gave action to their anger.

How the course of the Great War might have changed had Jaurès lived is, of course, impossible to know. He wouldn’t have stopped the war from starting. His effort to unite French and German workers in a common anti-militarist cause showed no signs of succeeding while he was alive. In August 1914, nationalism trumped proletarian solidarity.

But had Jaurès lived—and assuming he remained true to his fiercely anti-militarist views—he might have had a profound effect on French war policy. Once the high hopes of August 1914 gave way to the brutal realities of trench warfare, poison gas attacks, and staggering casualties, his war-is-madness message might have resonated with the French public. He might have forced Paris to drop its insistence on an unconditional German surrender and instead seek a negotiated peace. That might have put Europe on a very different course than the one it took.

Is that a far-fetched possibility? Perhaps. But Jaurès’s supporters certainly thought that he would have made a difference. As the novelist Romain Rolland later wrote: “The death of a single human being can mean a great battle lost for all humanity: the murder of Jaurés was one such disaster.”

As for Villain, he was jailed but not put on trial until 1919. He was acquitted, not because he was innocent, but because he was judged to have acted for patriotic reasons. He left France and eventually settled on the island of Ibiza. He lived there quietly for more than fifteen years. That all changed after the Spanish civil war began. In September 1936 he confronted Republican militiamen rummaging through his house. They shot him in the throat and left him on a beach to die. They warned villagers not to go to his aid. He lingered in agony for two days.