TWE Remembers: Washington’s Farewell Address

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

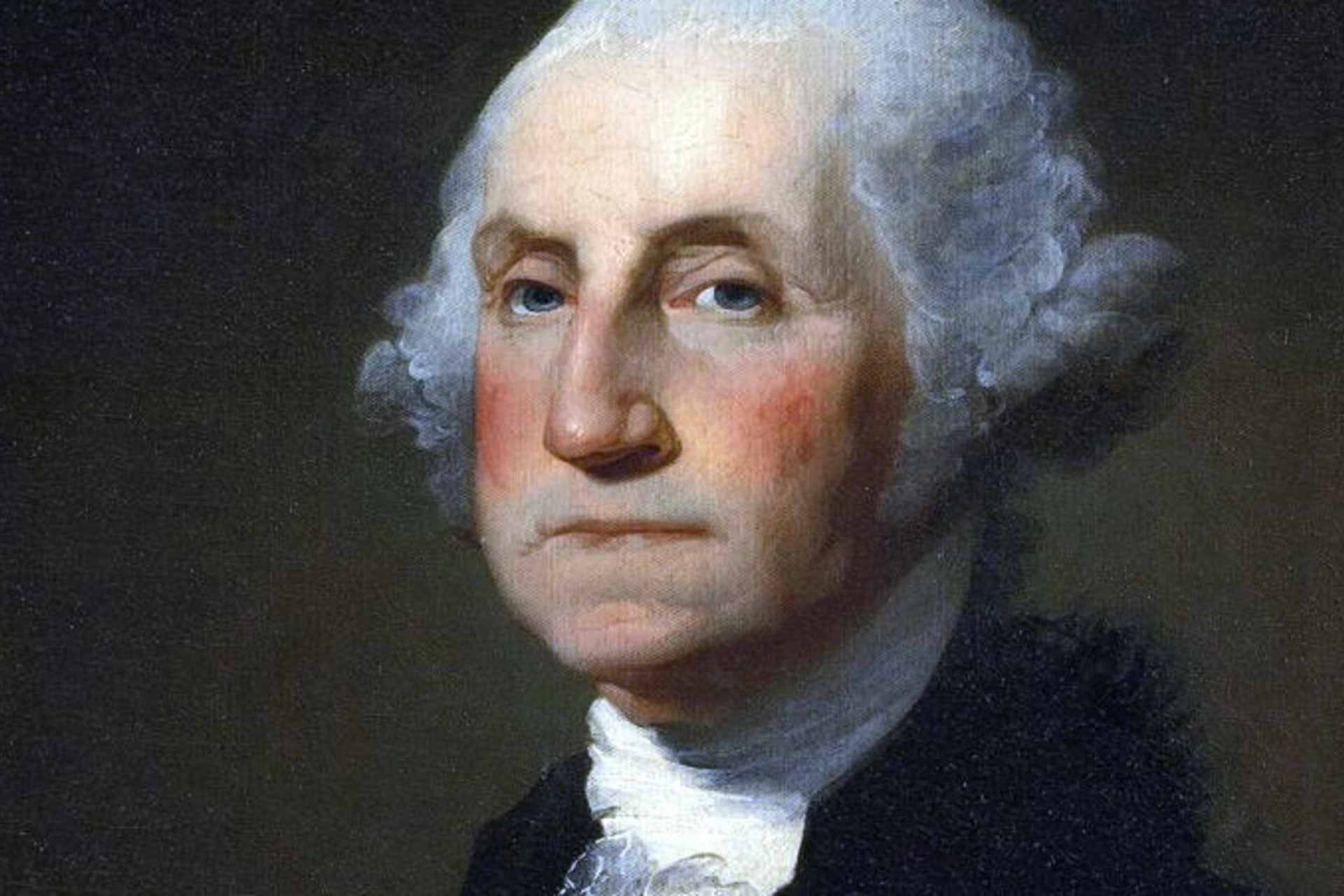

Today marks the anniversary of one of the most important presidential addresses in the history of the United States, “The Address of General Washington To The People of The United States on his declining of the Presidency of the United States,” or as it is better known, “Washington’s Farewell Address.” It was published, not delivered in person, on September 19, 1796 in the Philadelphia newspaper, the American Daily Advertiser. (Why a Philadelphia paper? Because Philadelphia was the nation’s capital in 1796.) More than two centuries later, politicians still cite Washington’s Farewell Address.

The Farewell Address summarizes Washington’s advice to the nation based on his more than four decades of public service. Much of what he wrote warns against the dangers of partisan and regional strife. But the address is best remembered for what it said about foreign policy, namely, that the United States should keep its distance from the affairs of Europe.

The Farewell Address’s nut paragraph (as journalists would put it) reads as follows:

The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements, let them be fulfilled with perfect good faith. Here let us stop. Europe has a set of primary interests which to us have none; or a very remote relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies, the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns. Hence, therefore, it must be unwise in us to implicate ourselves by artificial ties in the ordinary vicissitudes of her politics, or the ordinary combinations and collisions of her friendships or enmities.

Proponents of a less interventionist or non-interventionist American foreign policy frequently invoke Washington’s injunction that “it is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.” Recalling the address certainly gives historical roots to the argument for non-interventionism. But did Washington think that Americans should follow his advice for all time?

The balance of the evidence suggests that the answer is no. Rather than speaking to Americans a century or two in the future, Washington’s main purpose with the address was, as Robert Kagan has written, more “immediate and political”: to defend his foreign policy record against his critics and to warn his fellow citizens against a specific foreign policy choice that he thought would endanger the young republic.

That foreign policy choice was support for France. The 1790s was a time when Europe was wracked by the consequences of the French Revolution. Many Americans, with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison being the most notable, believed that the United States should side with France. They did so out of both revolutionary solidarity and gratitude for the pivotal aid that monarchical France had provided the colonists during the American Revolution.

Washington and his chief lieutenant, Alexander Hamilton, however, thought it ill-advised to side with France. They disliked the radicalism of the French revolutionaries, and they saw America’s interests lying with maintaining good relations with France’s arch enemy, Great Britain. Britain posed the far greater military threat to the United States, and it was America’s main trading partner. When Britain and France went to war in 1793, Washington declined to side with France, despite what Jefferson, who was secretary of the state at the time, saw as an obligation to do so arising out of a treaty the colonies had concluded with France. Washington instead issued the Neutrality Proclamation, which stated that the United States would neutral be in the fighting between the two European powers.

Jefferson’s followers lambasted Washington’s decision on grounds of both substance and procedure. The bad blood continued for the rest of Washington’s second term, with his critics going as far as to accuse him of treason. Washington was deeply wounded by the accusations, but also determined to stand his ground. He told Hamilton, “The people of this Country it would seem, will never be satisfied until they become a department of France: It shall be my business to prevent it.”

In Washington’s view, fulfilling that goal meant keeping Jefferson from succeeding him as president. To that end, he and Hamilton crafted the Farewell Address and released it two months before the presidential electors met in order to maximize the political damage they would do to the man from Monticello.

There is another reason to think that Washington never intended the Farewell Address to be a perpetual directive for American foreign policy. His first draft states unequivocally that the United States must “avoid connecting ourselves with the politics of any Nation.” Hamilton persuaded him to soften the claim to have “as little political connection as possible” with other countries. This formulation left the door open to potential alliances to foreign nations.

Although Washington probably never intended for subsequent generations of Americans to turn to his Farewell Address for foreign policy guidance, the events that prompted him to write it to illustrate a different point: the politics of American foreign policy have never stopped at the water’s edge.