Understanding the evolution of the US net international investment position

More on:

Predicting things can be difficult, especially if you are talking about the future.

So the Yogi Bera cliché goes. It rings true.

Back in 2004, I was fairly confident that the US net international investment position (defined here) was poised to deteriorate significantly. That, after all, is what usually happens if a country runs large, persistent current account deficits. Their external liabilities rise faster than their external assets.

A paper that Dr. Roubini and I wrote in 2004 – a paper that incidentally is still by far the most popular thing I have ever helped to write – made this argument. We recognized even then that US had one big advantage than most emerging economies lacked: its liabilities are denominated in dollars, while many of its assets are denominated in foreign currencies (mostly the euro and loonie). That means that falls in the dollar improve the United States external position. The falling dollar increases the value of many US external assets without changing the value of (most) US external liabilities. But by 2004 the dollar had already fallen significantly against Europe and Canada – which are still the home of the bulk of US investment abroad (especially if you discount the Caribbean as an offshore tax haven) – and we argued that it was unrealistic to expect that the US would enjoy similar valuation gains going forward.

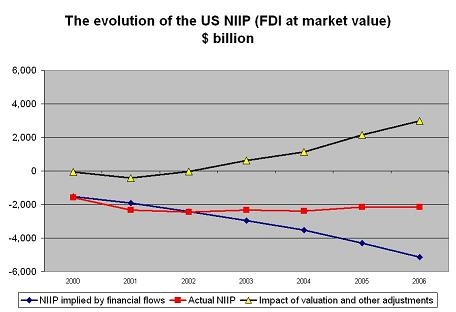

We were wrong. As the following chart – taken from the latest BEA data on the net international investment position – shows, the US net international investment position has actually improved since the end of 2004. Look at the red line. It has come back toward $2,000b ($2 trillion) since 2004, not gotten bigger -- even though ongoing financial flows continue to add new liabilities to the United States external balance sheet (the blue line)

One note – in this chart, I used the data series that values FDI as market value. The series with FDI valued at historic cost is similar, but not identical.

So why did the NIIP improve since 2004?

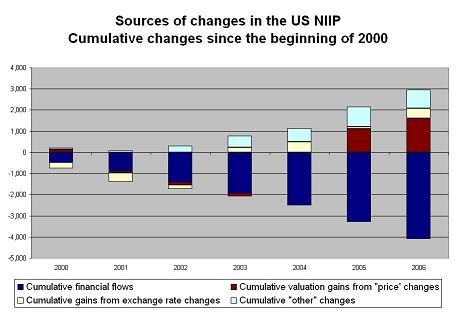

The Roubini/ Setser (2004) currency argument, though, was not totally off. The US hasn’t enjoyed big net gains from fx moves (basically a falling dollar) since 2004. The losses of 2005 offset the gains of 2006. Indeed, as the following graph – which plots the cumulative changes in the US net int. investment position since 2000 due to financial flows, currency moves, price moves and “other adjustments” – shows, currency moves (the white bar) have not been the main driver of the evolution of the net international investment since 2000.

Currency moves (the white bar) certainly don’t explain the large valuation gains the US has enjoyed on its external portfolio in 2005 and 2006.

Recent changes have come from what the BEA calls price changes – that is changes in the value of US equities and changes in the value of foreign equities that are not the result of currency moves Foreign equity markets – in terms of their own currency -- dramatically outperformed US equity markets – in dollar terms -- in both 2005 and 2006.

The data here is quite clear.

The implied return (in local currency terms) on US holdings of foreign stocks (portfolio equity) was 22.1% in 2005 and 18.4% in 2006. Throw in currency moves, which cut a bit over 7% off US returns in 2005 but added about 5.5% in 2006, and the gain -- in dollar terms -- on US holdings of foreign stocks in dollar terms was around 15% in 2005 and 24% in 2006.

That tops the 3.1% return foreigners got (in dollar terms) on US stocks in 2006, and their 13.2% return in 2006.

US equity investors abroad did about 12% better than foreign equity investors in the US in 2005 and about 11% better in 2006. They make it hard to argue (credibly) that the US can finance large deficits because the US is such a good place for investment ...

Some analysts like to emphasize that equity constitutes a higher share of the United States external portfolio than of foreign holdings in the US. But the US also has more liabilities than assets -- and in some cases, looking at the percentage shares of differently sized portfolios can be bit misleading. I prefer to compare total US holdings of equities to total foreign holdings of equities.

In 2000, US equity investment abroad was about equal to foreign equity investment in the US. At the end of 2006, US equity investments abroad were about $3 trillion larger from foreign equity investments in the US.

But I don’t think this implies – as some have suggested – that the US operates like a successful private equity firm, issuing debt to buy equity abroad.

Why not? To me, it makes sense to compare equity inflows to equity outflows. Net US purchases of equities have only slightly exceeded foreign purchases of US equity since 2000. The US hasn’t as a result, taken on a lot of debt to buy a lot of foreign equity. There has been a small net FDI outflow, but that seems tied to differentials in reinvested profits – a topic I’ll turn to in a later post. Basically, there haven’t been large net flows in either direction, at least not if you look at cumulative flows since 2000 (I’ll grant that this data is distorted by the 2005 homeland investment act. Because it led US firms to dramatically reduce their “reinvested earnings” in 2005, it produced a large net FDI inflow in the US in 2005, offsetting FDI outflows in other years. But even so, these FDI outflows are modest)

Indeed, in a lot of ways, I would argue that Europe now operates more like a private equity firm than the US. Europe sells a lot of debt to the world’s central banks – the latest data suggests over $200b of central bank purchases of euro-zone debt in 2006, and even bigger flows in 2007, as central banks have simply used their rapidly growing reserves to buy more of everything. And since the eurozone’s current account is in balance, all that cheap debt is available to finance external investment. The US takes on debt primarily to finance its deficit – not to invest abroad.

So why are US equity investments abroad now so much larger than foreign equity investments in the US? Simple: the United States had the good fortune to have accumulated large equity investments in Europe by 2000 and those investments have done far, far better since 2000 than foreign equity investments in the US.

Yes, that’s right, the strong performance of European equity markets has been the key reason why the United States’ external position hasn’t deteriorated. Standard American Euro-bashing for Europe’s structural deficiencies leaves this point out for some reason …

Of course, this raises another big question: why have foreigners continued to invest in the US rather than investing elsewhere if investments in the US have consistently performed less well than investments elsewhere?

Chasing under performance isn’t necessarily a great investment strategy.

You could argue that the United States recent under performance sets the stage for future out performance. But US “external adjustment” optimists universally bank on the opposite. They expect that US investment abroad will continue to do far better than foreign investment in the US, keeping the US NIIP from deteriorating and also holding the US income deficit down.

My explanation for the United States’ ability to finance large deficits even though foreign markets have done better than the US market? No surprise: central bank demand for dollars. Central banks core goal is to manage their own exchange rate – something that sometimes requires that they not seek the best risk-adjusted return.

Still, the United States’ official creditors would have been far better off if they had insisted that the US sell off its existing foreign assets to pay for its ongoing current account deficit, not just bought a lot of bonds. I suspect several have figured this out.

One last point: the gains from the out-performance of foreign markets and currency changes on their own are not large enough to explain the absence of deterioration in the US NIIP. There is another big reason why the US NIIP hasn’t deteriorated -- something that the BEA just calls “other changes.” The cumulative impact of these adjustments (the blue bar) has been quite large – close to a trillion dollars. Such changes seem to primarily come from the fact that the TIC data implies that foreigners have bought more US than show up in the Treasury’s survey of foreign holdings of US assets, and the NIIP data is ultimately based on the survey. Daniel Gross of CEPR is suspicious: a certain amount of US debt seems to consistently disappear into a black hole, reducing total external claims on the US.

And if you look at the details of the most recent NIIP data, it is pretty easy to see why the BEA recently revised the income balance in a big way. “Other changes” in 2005 were huge: $1.5 trillion on the assets side, and $1.1 trillion on the liabilities side. Those assets are assumed to receive interest payments -- and since the BEA discovered more assets than liabilities, the BEA's concluded that the US got a lot more interest income than it previously thought. As a result, well, the BEA concluded that the US current account deficit in 2005 and 2006 was something smaller than it initially thought.

Heaven forbid that any changes or adjustments work against the US.

For what it is worth, I still think the US NIIP will eventually deteriorate. The continued health of the US net international investment position requires :

-- ongoing cheap debt financing from China and others, but overwhelmingly from China

-- and the ongoing out-performance of European equity markets, so American equity investment in Europe rise in value faster than European equity investments in the US …

And I suspect even China won’t continue to finance the US at current rates if foreign markets continue to outperform the US market. There are rumors that China was selling dollars earlier this week … .

More on:

Online Store

Online Store