What Latin America Can Learn From Past Anticorruption Success

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Matthew M. TaylorAdjunct Senior Fellow for Latin America Studies

As Latin America reflects on its current wave of anticorruption successes—including the arrest of former Guatemalan president, Odebrecht prosecutions in Peru, and the ongoing Lava Jato cleanup in Brazil—it may be both sobering and heartening to consider the history of past anticorruption successes around the world.

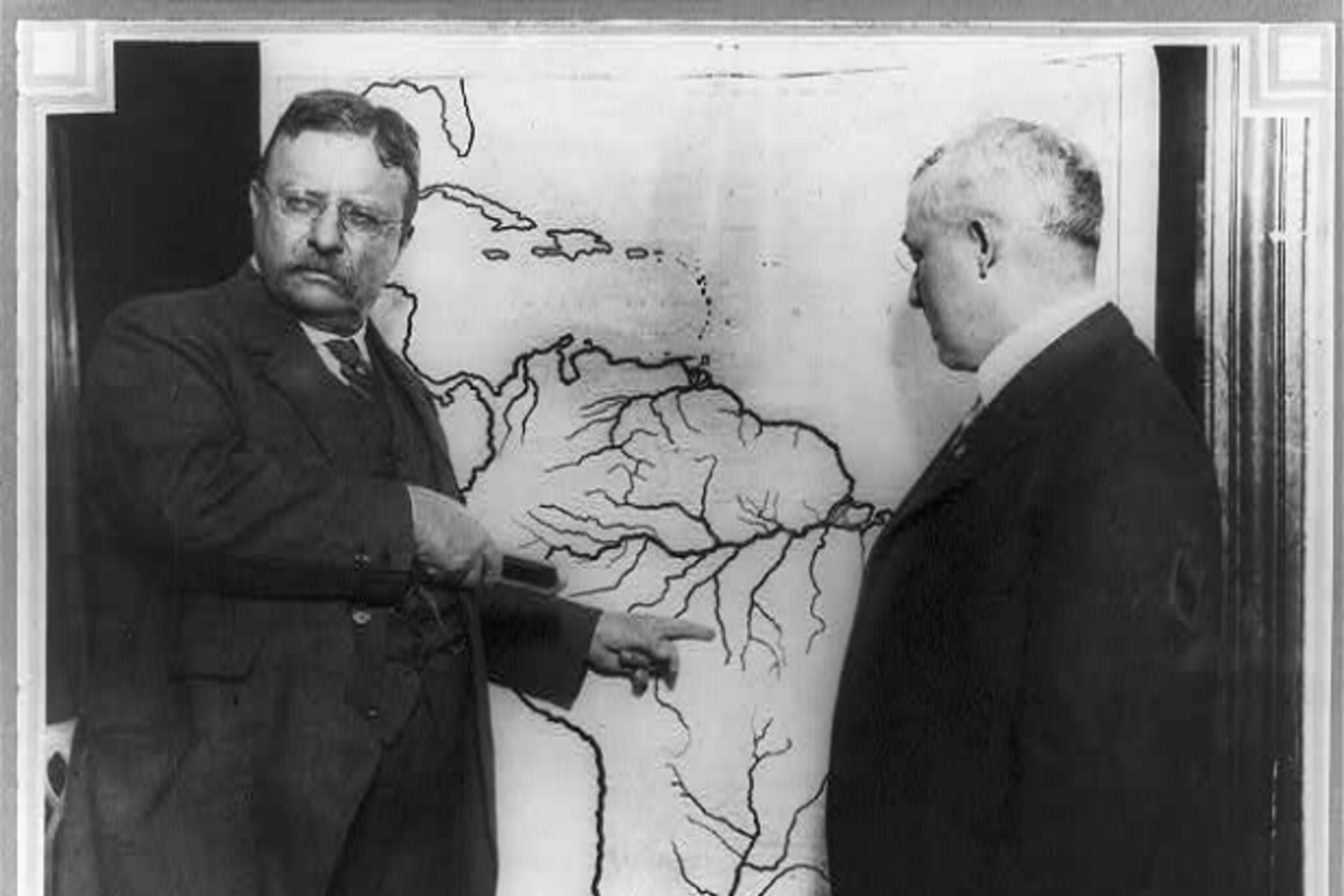

First, the sobering lesson. Even when things go well, other countries’ experiences suggest that an overall shift in the degree of corruption can take decades. Perhaps the best known example is the United States, where a series of disconnected local and national accountability efforts during the Progressive Era took place—including regulation of the trusts, elimination of patronage hiring in the civil service, and restrictions on corporate campaign contributions.[i] But although many of the reforms took place in the late nineteenth century, they only coalesced into a significant shift in the overall level of corruption in the U.S. between the 1920s and the New Deal. Summarizing a complex history, Glaeser and Goldin use press coverage of corruption to demonstrate an arc-like pattern: corruption rose steadily from 1815 to 1850, but began falling after 1870, reaching a stable lower-corruption equilibrium by the 1930s, where it remained until the 1970s (when the authors ceased data collection). Similarly, Bo Rothstein’s work on Sweden suggests that the process of significantly lessening the degree of corruption in that country was decades-long.[ii]

While the slow pace of these changes may be discouraging for Latin American publics frustrated by the damage and unfairness inflicted by persistent political graft and crony capitalism, it may be somewhat heartening to think that even small victories in the short term can trigger enormous development gains, by changing norms, removing dirty players from the political game, and most importantly, by consolidating public support for the continuation of the reform process. As Brazil’s outgoing prosecutor general Rodrigo Janot noted in Washington this week, there is no putting the genie back in the bottle: no matter where Brazil’s Lava Jato investigation goes, the public has shown that it will no longer tolerate the old cronyism between oligopolies and politicians.

Furthermore, the pace at which anticorruption gains accumulate may be faster in the twenty-first century than it could be in the nineteenth and twentieth. Countries as diverse as Georgia and Rwanda have made remarkable gains on most measures of corruption in the space of the past two decades. They have done so by drawing on a large set of international best practices, simultaneously improving transparency, oversight, institutional effectiveness and the likelihood of sanction. Latin American democracies that are already implementing such anticorruption strategies may also be able to benefit from vibrant political competition, which lessens oligarchic politics and increases the practical autonomy of courts and prosecutors, and a vibrant press, which has proven essential to uncovering wrongdoing and mobilizing civil society. Finally, the international anticorruption framework is much stronger than ever before—the record-breaking Odebrecht settlement with Swiss, Brazilian, and U.S. officials being only the latest example—which enhances global support for reformers while increasing the likely international penalties against potential bribe-takers. So although the path to improvement will be a long one, it may be possible for Latin American reformers to move more quickly than was possible in the not-so-distant past. That alone is grounds for optimism, although a healthy dose of realism is also needed in the face of widespread pushback from the guardians of the status quo.