By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Benn SteilSenior Fellow and Director of International Economics

By Benn SteilSenior Fellow and Director of International Economics

By

- Benjamin Della RoccaAnalyst, Center for Geoeconomic Studies

After the 2008 financial crisis, it took five years of quantitative easing (QE) for the Fed’s balance sheet to grow $1.8 trillion. This year, once the pandemic began, it took less than five months.

With interest rates once again at the zero lower bound, the Fed is tapping every tool it has to ease policy and prevent deflation. Its assets are ballooning at unprecedented speed. It has, for the first time ever, entered markets for corporate bonds. Aiming to boost inflation expectations, Fed Chair Jerome Powell last month broke with longstanding Fed messaging by saying he would tolerate inflation over two percent “for some time.”

Observers are divided over the likely effects of the new policies. Some commentators fret that the asset purchases could bring runaway inflation—or even hyperinflation. Others counter that with the United States in deep recession, not even aggressive QE will make prices go up. But the data suggest that neither concern is merited. A timely return to modest inflation is the most likely result. In this post, we explain why.

One important way QE is meant to cause growth and inflation is by the so-called credit channel—that is, by coaxing banks to increase lending. When the Fed uses QE to expand its balance sheet, it buys up Treasury bonds and other securities from banks. These purchases increase banks’ cash reserves. Rising reserves give banks a liquidity cushion which should, so the logic goes, encourage them to lend—notwithstanding the fact that a bad economy makes lending riskier.

How well this works depends, of course, on whether banks really do make more loans as their reserves rise. If banks just stockpile reserves, QE won’t cause inflation—let alone the hyperinflation some fear.

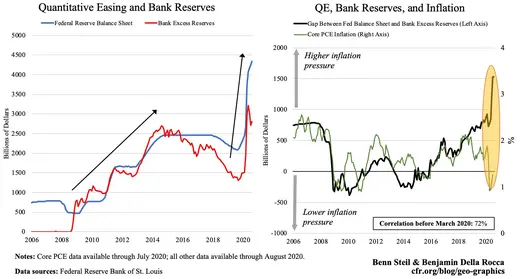

Stockpile is exactly what the banks did during the so-called Great Financial Crisis, from 2009 to 2015. As the left-hand figure above shows, banks’ excess reserves rose in close tandem with the Fed’s balance sheet during these years. In consequence, inflation, despite fears that it would run wild, stayed flat.

The left-hand figure also shows the same pattern emerging in March of this year, when the Fed restarted QE. The Fed’s balance sheet rose by $1.6 trillion, while bank excess reserves rose by $1.7 trillion.

More recent data, however, show a big change. Since June, as QE continued to balloon the Fed’s balance sheet, bank excess reserves have turned sharply downward. In consequence, as the right-hand figure shows, the gap between the Fed’s balance sheet and bank excess reserves, which had closely tracked inflation throughout the post-crisis era, has hit new highs. If this trend persists, inflation should head upward in tandem.

When, then, can we expect inflation to hit the Fed’s Holy Grail of 2 percent? Well, we know that when our balance-sheet-to-reserves gap measure began rising in 2010 it took eight months for inflation to rise one percentage point from the time it subsequently bottomed out. If inflation should rebound at the same pace now, we are looking at 2 percent Core PCE inflation, the Fed’s preferred measure, in February 2021.