Does Washington Have a Stake in the Sahel?

U.S. strategic interests in Africa’s Sahel have been marginal for decades, but there is a strong case for expanding ties with regional allies to quell a spreading security threat, write J. Peter Pham and CFR’s John Campbell.

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- John CampbellRalph Bunche Senior Fellow for Africa Policy Studies

- J. Peter PhamVice President for Research and Regional Initiatives and Director, Africa Center, Atlantic Council

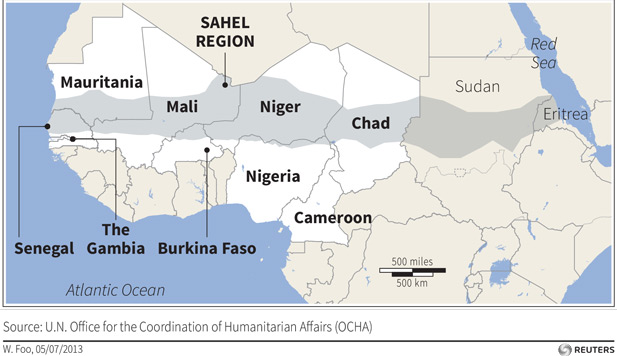

Long known as a region of weak, poorly governed, corrupt states, Africa’s Sahel is fast becoming more salient for the outside world. The challenges of radical Islam, narcotics trafficking and other criminal networks, and growing environmental stress are taxing the capacity of Sahelian governments. Many of these states have asked the United States and its allies for assistance. Partners of the United States with Sahelian interests, notably France, Morocco, and Nigeria, are also seeking increased U.S. involvement.

The Obama administration has been responsive to the appeals in piecemeal fashion. In the aftermath of France’s January 2013 intervention in Mali, the United States established a base for unmanned aerial vehicles in neighboring Niger at the request of its government and the Hollande administration in Paris. Washington provides training and logistical assistance to local militaries, especially those involved in international peacekeeping and counterterrorism missions.

In late 2013, the U.S. State Department designated Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s Sahel-based al-Mulathamun Battalion as a foreign terrorist organization, citing it as the group posing the greatest threat in the area to U.S. interests. Earlier in the year, it similarly designated Nigeria’s Boko Haram and Ansaru. Nevertheless, overall U.S. engagement in the Sahel remains minimal.

But is the Sahel strategically important to the United States? Does it meet the threshold for the deployment of additional resources, especially during a period of military downsizing? Or should the United States, in cooperation with like-minded partners, develop a comprehensive regional strategy to prevent the Sahel from becoming the center of what the UN Security Council recently characterized as a new “arc of instability” stretching “from Mauritania to Nigeria and beyond to the Horn of Africa”? U.S. interests are marginal at present, but the region requires more attention, including a heightened diplomatic presence and a more vigorous conversation with U.S. regional partners.

U.S. Foreign Policy Interests

It is worth examining how the Sahel measures up in the three broad rubrics used to measure U.S. interests in many parts of the world: economics, security, and the development of democracy with promotion of human rights.

- Economics: The Sahel is no El Dorado in the sand. There is a widespread myth of Sahelian mineral and other riches, but after a generation of exploration, little has been found. The French oil and gas giant Total has been prospecting and drilling for at least two decades, and its discoveries are marginal. There are significant phosphate deposits, but they are largely controlled by the Moroccan government, which is a close ally of the United States. That said, the region does have some valuable reserves. Niger’s uranium deposits, which yielded $500 million in 2010, are largely controlled by the French, who also have a number of other economic interests in the region.

In the aggregate, trade and investment in the Sahel for the United States is insignificant. But not for the French, Nigerians, Algerians, Chinese, and South Africans—the latter dominating the region’s gold mining sector, especially in Mali, where gold is the country’s leading export commodity and production has expanded even through the crisis. - Security: Smuggling, especially of persons and narcotics, abounds in the Sahel. Kidnapping is also prevalent, focused on Westerners whose governments will pay ransoms. There can be significant overlap among smugglers, kidnappers, and jihadi groups. Belmokhtar’s organization, for example, smuggles cigarettes while also pursuing jihadist-style terrorism against Algeria and Western targets. Were such groups to become more powerful, it is highly unlikely that they would focus on the United States. Europe is much closer at hand, and jihadis and associated groups are not powerful enough to threaten the United States. It is true, however, that an individual or a small group from the region might seek to wreak havoc, such as Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, the “underwear bomber” who sought to destroy an aircraft over Detroit on Christmas Day, 2008. But such an individual could be based anywhere.

Narco-trafficking is on the upswing in the region, and Guinea-Bissau is close to being a narco-state. In 2012, the UN Office of Drugs and Crime estimated that thirty tons of cocaine from South America transited the Sahel, en route to Europe, generating $1.2 billion in profits for trafficking networks, some $500 million of which was laundered in local economies. By comparison, in 2010, only eighteen tons of cocaine moved through the Sahel to Europe. However, from the perspective of U.S. interests, the narcotics are largely destined for Europe, not the American market. A strong argument can also be made that the best venue for narcotics interdiction is not in the Sahel but in the Gulf of Guinea, where existing efforts should be expanded. - Democracy and Human Rights: For the United States, with little expertise in the Sahel and virtually no previous presence there, any role in promoting democracy is bound to be minor.

Overall, U.S. interests in the Sahel are marginal, but the region is of increasing importance to friends and allies, notably France and Morocco. The close U.S.-France relationship has positive ramifications worldwide, while Morocco can be an important partner in the Middle East as well as sub-Saharan Africa. This was acknowledged in the joint statement following King Mohammed VI’s meeting with President Obama at the end of 2013, which pledged both countries to explore initiatives to promote human development and stability in the region.

What should the United States do?

Developments in the Sahel are dynamic. It is possible that the currently largely inchoate jihadist movements could consolidate and transform themselves from their current local focus to the international sphere. Hence, the United States cannot ignore the Sahel.

Nevertheless, given current realities, the United States requires no boots on the ground in the Sahel. But it does need ears and eyes that focus on humanitarian issues–such as food security–as well as security issues. That would require greater investment in diplomatic activities. With the exception of Nigeria, the U.S. diplomatic presence in the Sahel is miniscule. For example, at present in the Central African Republic, the U.S. embassy has been closed since December 2012 for security reasons.

There are a total of eight Americans on the Niger diplomatic list. Even in Nigeria, there is no diplomatic presence north of Abuja, a region with at least seventy million people and comparable in size to half the state of Texas. Beefed up diplomatic capabilities could also enable the United States to create friends and build networks if a more robust future engagement is required.

In a period of constrained fiscal resources, the U.S. government needs to reexamine the effectiveness of its aid programs in the Sahel. In addition to security-focused programs, the United States provided its eleven partners in the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership with nearly $6.5 billion in official development assistance during the first decade of the current century, mostly through USAID, although three countries (Burkina Faso, Morocco, and Senegal) also qualified for Millennium Challenge Corporation funds. During the same period, European Union countries and EU institutions provided an additional $52 billion in aid.

In particular, it is necessary to rethink the heavy emphasis in border security that has characterized many post-9/11 “capacity-building” programs for Sahelian countries, especially given that the geographical space and social and economic networks crisscrossing the region render the policing of artificial lines in the sand rather pointless. Jihadist activities in Mali and northern Nigeria and their spillover into Cameroon, Niger, and southern Nigeria indicate that border security programs in the region have largely failed.

There is much to be said for “leading from behind” in the Sahel, that is, deferring a leadership role to close allies and supporting them where it is in U.S. interests to do so. Here, U.S. support of France should be paramount. The Sahel is a region of general interest and concern to France, which has had much experience there. The French led the pushback of the jihadis in Mali with African fig leaves provided by the Malian army and forces from the Economic Community of West African States.

At France’s request, the United States provided some diplomatic, logistical, and intelligence support for that operation. The United States established the drone base outside of Niamey, with the support of the government of Niger. The United States was also indispensable in securing UN Security Council endorsement for the intervention by France and certain African states in Mali. The Mali scenario might provide a useful template for response to jihadist radical Islamists elsewhere in West Africa.

J. Peter Pham is the director of the Africa Center at the Atlantic Council. John Campbell is the Ralph Bunche senior fellow for Africa Policy Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.