Indonesia’s Election: Democracy at Risk?

The country’s next president must bridge the ethnic and religious divisions that could destabilize the booming Muslim-majority democracy, explains CFR’s Karen Brooks.

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Karen B. BrooksAdjunct Senior Fellow for Asia

Recent political unrest in parts of the Middle East has led many Western analysts to question the compatibility of Islam with democracy, but Indonesia—the world’s most populous Muslim country—is looking to tell a different story, the next chapter of which begins this week.

An important country about which most Americans know little, Indonesia is the world’s third-largest democracy, after India and the United States, and the tenth-largest economy. In recent years, it has enjoyed high growth, low inflation, an extremely low debt-to-GDP ratio, a strong stock market, and record-breaking exports and foreign direct investment.

Indonesia’s economic success has been built on the back of its even more impressive democratic development. In just a few years, after the fall of longtime strongman Suharto in 1998, the country transitioned from a tightly controlled authoritarian system to one of the most vibrant democracies on earth. Through three successive cycles of democratic elections—in 1999, 2004, and 2009—Indonesia has been hailed as a model of an open, moderate, tolerant, multiethnic, and multireligious society.

Presidential elections in Indonesia are among the most free in the world, with a “one man, one vote” system that is not intermediated by an electoral college, as in the United States. Indonesians have embraced this freedom with great fanfare over the past fifteen years. In Indonesia’s first democratic election, in 1999, more than 93 percent of its roughly 150 million voters participated. I had the privilege of monitoring that first election, which was broadly praised as free, fair, nonviolent, and well run, despite the absence of any democratic traditions in the country since the 1950s. While some of the initial euphoria about elections declined in subsequent contests, voter participation has remained above 70 percent in every cycle.

This week, Indonesians are set to test and, hopefully, build on that record as they choose a new president in the most hotly contested race in the country’s history. The race is a nail-biter, with the candidates polling within several points of each other—in some polls, within the margin of error and with a margin smaller than the number of undecided voters. The uncertainty of the outcome has left both the people of Indonesia and its markets on edge.

This is the first time that the incumbent is term-limited. President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono has served two five-year terms and cannot run again due to constitutional reforms. His party, moreover, did not win enough seats in the April legislative elections to field a candidate for the presidential race. For the first time in Indonesian history, the party in power is not fielding a candidate for the top job.

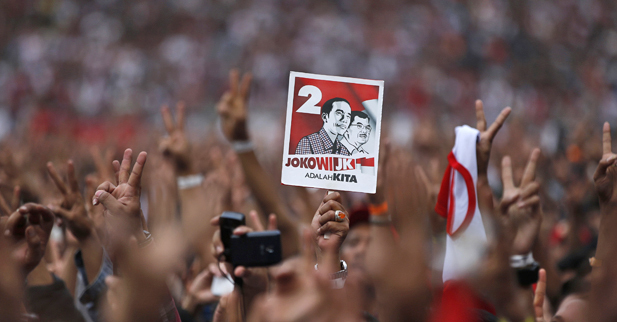

This election is also the first head-to-head contest, with the popular governor of Jakarta, Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, running against the charismatic former commander of the Indonesian special forces and former Suharto son-in-law, Prabowo Subianto. In all previous election cycles, three or more contenders have vied for the presidency.

The race has forced the candidates to make clear distinctions between each other and led the other parties that won seats in the incoming legislature to quickly choose sides. With four of the five Islam-based parties supporting Prabowo, his coalition is perceived as more Islamic, while the coalition backing Jokowi is perceived as more secular and nationalist.

This divide dates back to the founding of the Indonesian state, when leaders of the struggle against the Dutch colonial power were writing a constitution in preparation for their declaration of independence. One of the primary debates among the independence leaders was whether the new state should be Islamic or essentially secular, but rooted in God. Those in favor of the latter won the day, arguing that the archipelago’s ethnic and religious diversity demanded an open paradigm that defined the state as broadly as possible.

There is some overlap between the two coalitions, with the secular-nationalist Golkar party backing Prabowo, and the Islam-based National Awakening Party (PKB) backing the Jakarta governor, for example. But the relatively defined character of each coalition has given Indonesian voters a clearer choice than in past elections and should be healthy for the consolidation of the country’s democracy.

The personalities of the two candidates could not be further apart. Jokowi is a largely untested, understated, and untainted “man of the people,” beloved for his integrity and inclusiveness by Indonesia’s poor and lower middle class. Prabowo is a self-styled strongman with compelling oratory skills and a record of military experience that appeals to the upper-middle and upper classes, which yearn for strong leadership after a decade under Yudhoyono. Prabowo has been dogged by allegations of human rights abuses during his military career, including the torture and disappearance of protesters during the turmoil that brought down his father-in-law and violent suppression of dissent in hot spots like West Papua and East Timor, a former province that is now an independent state. Indonesians, however, have famously short memories, and with more than half the country under the age of thirty, few voters either know or care much about Prabowo’s dark past.

In recent months, Prabowo has closed the gap with the Jakarta governor, who was leading by as many as 30 percentage points. While this heated competition is in many ways a good thing for Indonesian democracy, it has also unleashed a dark side of Indonesian politics, with a raft of smear campaigns, largely against Jokowi, flooding social media—Indonesia has the second-largest Facebook community in the world, after the United States—and tabloids. They have accused Jokowi of being everything from Chinese and non-Muslim to a communist. While none are true, the ferocity and relentlessness with which these charges have circulated have hurt the governor in a country that is still overwhelmingly Muslim and anticommunist.

More importantly, these campaigns have brought race and religion to the fore in an ugly and highly divisive manner, a real concern for a country of such diversity and one that has a history of ethnic and religious violence. Indeed, the role of media in this campaign has been more controversial than at any time in the past, with outlets owned by businessmen aligned with one ticket or the other providing highly partisan coverage and undermining Indonesia’s reputation for a free, independent, and neutral press.

This race is not only the tightest in Indonesia’s democratic history; it’s also widely seen as the dirtiest, raising fears of a close outcome—perhaps with a margin of less than 2 percent—that could get bogged down in court challenges and even give way to violence. Passions are running high across the country. Some reports suggest that minorities are afraid to vote and that a climate of intimidation exists in some of the most contested areas.

Indonesia has achieved great things over the course of its fifteen-year experiment with democracy, but the ugliness of this race reminds us that such progress cannot be taken for granted. At a time when political restructuring in the Middle East continues to challenge the notion that Islam and democracy can coexist, and when pluralism and tolerance are under attack around the world, Indonesians hope to rise above these provocations and cement the country’s place as a vibrant Muslim-majority democracy.