How to Improve U.S.-China Relations

The U.S.-China summit comes amid tensions over cybersecurity and regional disputes and crucial questions about economic policy. Five experts weigh in on how to manage the relationship.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Adam SegalIra A. Lipman Chair in Emerging Technologies and National Security and Director of the Digital and Cyberspace Policy Program

By Adam SegalIra A. Lipman Chair in Emerging Technologies and National Security and Director of the Digital and Cyberspace Policy Program

By

- Duncan Innes-KerRegional editor, Asia, Economist Intelligence Unit

- Elizabeth C. EconomySenior Fellow for China Studies

- Shen DingliProfessor and Associate Dean, Institute of International Studies, Fudan University

- Orville H. SchellDirector, Center on U.S.-China Relations, Asia Society, Director, Center on U.S.-China Relations, Asia Society

- Eleanor AlbertOnline Writer/Editor

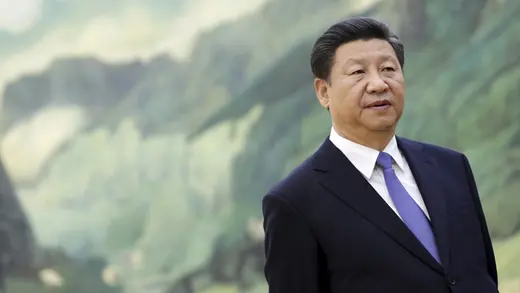

This month’s state visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping to the United States comes at a time of extensive bilateral economic ties and cooperation across a range of issues including security, energy, and climate change. But points of contention have also multiplied, including China’s ongoing land reclamation in the South China Sea and the threat of U.S. sanctions against Chinese entities accused of cyber theft. Five experts—Duncan Innes-Ker, Elizabeth C. Economy, Shen Dingli, Adam Segal, and Orville Schell—offer recommendations for how the two sides can navigate their expanding relationship.

Duncan Innes-Ker, Regional editor, Asia, Economist Intelligence Unit

China’s economy is changing dramatically, once again, moving away from its past focus on exports and investment toward more consumption-driven growth. For the United States, as for the rest of the world, it is important to keep abreast of these shifts. Some past U.S. gripes remain valid. Local—and sometimes national—Chinese authorities continue to hamper the rationalization of capacity in their domestic industries, especially when it comes to state-owned enterprises. This, coupled with the slowdown in China’s demand for construction goods, means that excess capacity is likely to spill over into international markets. As a result, there will be solid grounds for pushing for anti-dumping duties in many sectors, such as steel. Yet other complaints from Washington are outdated. Notably, the renminbi is no longer undervalued, and U.S. politicians who argue that it is do themselves and U.S.-China relations no favors.

U.S. officials should help to pry open China’s services sector.

Duncan Innes-Ker, Regional Editor, Asia, Economist Intelligence Unit

Though China’s overall economic growth is slowing, spending by its consumers is continuing to grow at a very rapid pace. This offers huge potential opportunities to foreign businesses. Ensuring that U.S. companies are able to access these opportunities should be the main focus for both current and future U.S. administrations, particularly in the ongoing discussions over a bilateral investment treaty. Among other things, U.S. officials should help to pry open China’s services sector. This sector is now the main driver of China’s economic growth, but fields such as finance, entertainment, and telecommunications remain dominated by state enterprises, and are still too closed to foreign firms. The United States should be prepared to relax its tough approach to Chinese inbound investment, if China, in turn, is willing to liberalize access to these sectors. The two sides each have valid concerns about the security risks that would accompany such a move. However, it would have huge economic benefits for both nations and could also reduce mutual suspicion.

China’s ambitions on the global economic stage are increasing, but it falls some way short of fulfilling the sort of role that would be expected of the world’s second largest economy and biggest trader. Still, the rise of China-backed institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank should be welcomed as a positive and constructive response to the failure of other powers (most notably the United States) to allow it greater influence in bodies like the IMF and World Bank.

Elizabeth C. Economy, C.V. Starr Senior Fellow and Director for Asia Studies, Council on Foreign Relations

In the often fractious U.S.-China relationship, climate change has emerged as one of the few areas of genuine bilateral cooperation. Both countries have developed a long list of cooperative ventures in areas such as clean coal technology and electric grid development and have adopted side-by-side pledges to reduce carbon emissions (albeit at different paces and scales) with an eye toward providing momentum to global climate change negotiations. To build upon this foundation of cooperation, the two leaders should focus on the following three areas:

The United States and China must ensure that they fulfill their own climate commitments.

Elizabeth C. Economy, C.V. Starr Senior Fellow and Director for Asia Studies, Council on Foreign Relations

First, Washington and Beijing should take stock of the successes and failures of the past twenty years of cooperative efforts to understand what works and what does not. Several joint efforts announced in the late 2000s, such as that between Ford and Chang’an Automobile to develop electric and hybrid cars, have not come to fruition. Before pushing ahead with more projects, it is important to ensure the success of those already underway.

Second, as the world’s leading sources of foreign direct investment, the United States and China, along with the European Union and Japan, should develop a shared financing and investment framework that complies with best climate practices. Given the developing world’s enormous infrastructure needs, adopting strategies and technologies that would limit the impact of development on climate change is essential. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank—despite the lack of formal participation by the United States—could lead the way.

Third, and most important, both United States and China must ensure that they fulfill their own climate commitments. As China’s economy slows, some climate benefits such as falling coal consumption will likely follow. It is also possible, however, that there will be pressure to relax rather than tighten environmental regulations. In the United States, President Obama continues to fight an uphill battle with Congress over his efforts to strengthen the U.S. climate commitment. In his remaining year in office, he needs to institutionalize his policies. If Presidents Obama and Xi cannot deliver at home, they will not be able to deliver abroad.

When Presidents Obama and Xi meet in Washington, DC, in late September, the temptation will be strong to announce more areas of cooperation. For now, however, more attention needs to be paid to fulfilling promises of cooperation rather than making new ones.

Shen Dingli, Professor and Associate Dean, Institute of International Studies, Fudan University

Interaction between China and the United States is expanding. Bilateral economic and trade ties have deepened and continue to be mutually beneficial. The China-U.S. security relationship is developing, too. Beijing and Washington collaborate on a number of international security issues, including anti-terror initiatives, and nonproliferation.

China and the United States should seize opportunities to work together.

Shen Dingli, Professor and Associate Dean, Institute of International Studies, Fudan University

As the two broaden their security ties, Beijing and Washington also confront increasing challenges. China’s rising power makes some of its neighbors wary of China’s aspirations and next moves. Asia-Pacific’s security order is evolving. China, through its declaration of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the East China Sea and its land reclamation in South China Sea, has actively changed the region’s security landscape, potentially boosting its strategic position.

China argues that such moves are justified. Leaders in Beijing argue that if Japan can “nationalize” the disputed Diaoyu/Senkaku islands, why should China not be able to send its government vessels to these waters? Why was China’s ADIZ condemned, if the United States, Japan, and others have declared similar zones? Why should China not engage in land reclamation efforts in the South China Sea, if Vietnam, the Philippines, and other claimants have long pursued such activities?

Historical narratives in Beijing, Washington, and other capitals in the region reflect diverging views over what Asia’s security order should be. Will the Asia-Pacific region’s security be contingent on ongoing American dominion or will a Chinese-led security architecture emerge? This very question tests Washington’s willingness and ability to accept Beijing’s proposal for a “new type of major power relations. ”

To overcome mutual suspicion, both parties should follow some guiding principles:

- abide by international law, establish common standards of action in the Asia-Pacific, and improve communication lines and increase transparency;

- preserve as much as possible the status quo. The use or threat of force undermines the existing security order;

- maximize efforts to manage and resolve differences through peaceful means;

- notify one another ahead of any major security move to bolster mutual confidence and collaborative security.

China and the United States should seize opportunities to work together and to benefit mutually from a stable security environment.

Adam Segal, Ira A. Lipman Chair in Emerging Technologies and National Security and Director of the Digital and Cyberspace Policy Program

While cybersecurity has been on the agenda of previous meetings between President Obama and President Xi, the upcoming summit will be the first time that the issue seriously threatens to destabilize the bilateral relationship. Recent press reports suggest that Washington is considering sanctioning Chinese individuals or entities that benefit from cyber theft, amid calls for cancelling the summit or downgrading it to a working meeting.

Neither side wants cybersecurity to derail the bilateral relationship.

Adam Segal, Ira A. Lipman Chair in Emerging Technologies and National Security and Director of the Digital and Cyberspace Policy Program, Council on Foreign Relations

The United States and China have serious differences on cyberattacks and the rules of cyberspace as well as how to ensure the security of the hardware and software of each country’s information and communications infrastructure. Washington and Bejing have framed cyber attacks as threats to national and economic security. But the gap between the two sides on cyberespionage will not be closed. Neither side is willing to restrain its own activities against the other. The perceived benefits from intelligence gathering are too high, the costs inconsequential.

Still, Washington and Beijing have a common interest in preventing escalation in cyberspace. Some attacks may be viewed as legitimate surveillance by one side but as prepping the battlefield by the other. In this climate, there are a few steps each side should take:

- The United States and China should broaden and deepen discussions on possible thresholds for use of force in cyberspace and provide greater transparency on their respective offensive cyber doctrines;

- If the White House has decided to levy sanctions after the summit, Obama should clearly explain to Xi how they will be implemented and what evidence the United States has of the hacking. Beijing continues to question Washington’s ability to attribute attacks.

- In June at the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue in Washington, Chinese State Councilor Yang Jiechi called for China to work with the United States to develop an “international code of conduct for cyber information sharing.” While there have been no further details from the Chinese side, Obama should pick up on the offer to discuss the types of information that are adequate to identify an attacker, thereby setting a standard that could be shared by the two sides.

Neither side wants cybersecurity to derail the bilateral relationship. The summit is unlikely to produce any concrete agreements, but hopefully the two sides will agree to further expand discussion on shared interests.

Orville H. Schell, Director, Center on U.S.-China Relations, Asia Society

As U.S. and Chinese heads of state gather for another summit, the vexing question of human rights looms larger than ever. The issue plagues the overall health of the bilateral relationship like a low-grade infection. U.S. displeasure with China’s rights record is only matched by Beijing’s displeasure with Washington’s judgmental attitude. This standoff has created an increasing sourness in relations that have made it difficult leaders from both countries to feel at ease with one another. The result is that the two countries have struggled to establish the élan and comfort level required for solving problems where real common interest is shared.

The United States and China have fundamentally irreconcilable political systems and antagonistic value systems.

Orville H. Schell, Director, Center on U.S.-China Relations, Asia Society

Disagreement over human rights grows out of a more divisive problem that sits unacknowledged like the proverbial elephant in the room. Because nobody quite knows what to do, we are hardly inclined to recognize, much less discuss it: the United States and China have fundamentally irreconcilable political systems and antagonistic value systems. If we want to get anything done, we must pretend that the elephant isn’t there.

President Xi Jinping has made it abundantly clear that his China is not heading in any teleological direction congruent with Western hopes. Xi seems to suggest that China has its own model of development, one that might be described as “Leninist capitalism,” with rather limited protection of individual rights. This is a model with so-called “Chinese characteristics,” which, in the world of human rights, means that China will emphasize collective “welfare rights,” such as the right to a better standard of living, a job, and a freer lifestyle, rather than emphasizing individual rights like freedom of speech, assembly, press, and religion.

But if this is the model, then the United States and China are heading in divergent historical directions. A host of new friction points now center around the abridgement of individual rights in China: arrests of human rights lawyers, growing restrictions on civil society activities, new controls on academic freedom, a more heavily censored media, more limited public dialogue, visas denied to foreign press, and domestic journalists and foreign correspondents suffering more burdensome forms of harassment. These trends grow out of differences in our systems of governance and values.

Whether we should confront these differences head on or seek some artful way to set them aside so the two countries can get on with other serious issues of common interest is a question we have hardly dared even think about. The elephant is still in the room, and the fact that no one knows quite how to address it lays at the root of our human rights disagreements. These differences often gain such an antagonistic dimension that they not only inhibit our ability to make progress on the rights front, but also undermine the rest of the U.S.-China relationship.