Time Ripe for Iranian Nuclear Accord?

A deal to tame Iran’s nuclear program is within sight, but a number of potential pitfalls, including an untimely increase in U.S. sanctions, could derail diplomacy, says expert Suzanne Maloney.

October 17, 2013 3:18 pm (EST)

- Interview

- To help readers better understand the nuances of foreign policy, CFR staff writers and Consulting Editor Bernard Gwertzman conduct in-depth interviews with a wide range of international experts, as well as newsmakers.

It’s "very much possible" for world powers and Iran to achieve an agreement on the latter’s nuclear ambitions, says Suzanne Maloney, a longtime expert on the Islamic Republic. "But it’s also not inevitable." In addition to concerns about enrichment levels, Maloney says that negotiators from the so-called P5+1 (United States, Britain, France, Russia, China, and Germany) will focus intensely in the coming months on Iran’s development of advanced centrifuge technology and a heavy-water reactor set to come online next year. Meanwhile, she says that talks could be sidetracked by additional U.S. sanctions, which are due up for Senate debate in the near future.

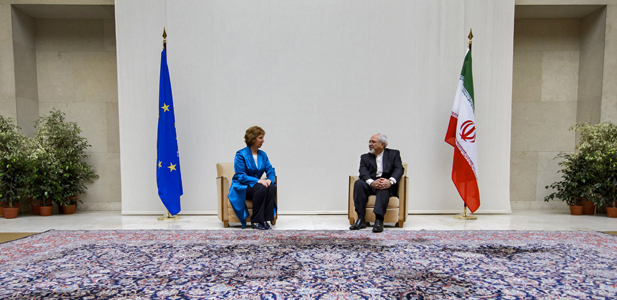

European Union foreign policy chief Catherine Ashton speaks with Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif before the start of nuclear talks at UN offices in Geneva (Fabrice Coffrini/Courtesy Reuters)

European Union foreign policy chief Catherine Ashton speaks with Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif before the start of nuclear talks at UN offices in Geneva (Fabrice Coffrini/Courtesy Reuters)The major powers and Iran just concluded two days of what from all accounts were very positive talks. This was a continuation of the constructive atmosphere during the UN General Assembly when the newly elected Iranian president Hassan Rouhani and foreign minister Javad Zarif were in New York. Where do you think we go from here? The nuclear talks will continue in early November.

More on:

It’s very much possible to get a deal between the United States, its international partners, and Iran on the nuclear issue within the span of a year, but it’s also not inevitable. What we saw this week was an important and constructive beginning that has been a long time in the making. The international community has been talking to Iran about its nuclear ambitions and activities for well over a decade, and the United States has been prepared to be a participant in those dialogues since 2006.

And yet never before have we had what took place over the course of the past few days in Geneva, which was apparently a very serious, technical discussion about how Tehran can meet the concerns of the international community for greater transparency and greater assurance that the Islamic republic cannot break out and achieve nuclear weapons capability.

The Iranians have made it clear, though, that they want to continue to enrich uranium. We don’t know whether they are willing to stop at this 20 percent figure. What does the magic figure mean?

There are both qualitative and quantitative constraints that the international community is looking to see Iran apply to its enrichment activities. The UN Security Council resolutions that have been passed over the course of the past seven years all refer to a requirement of a suspension of uranium enrichment, which was of course the condition—the concession—that now President Rouhani negotiated while he was in charge of the talks for Iran from 2003 to 2005.

There has been for some time an understanding among most in the international community that it is no longer viable to achieve a sustained suspension of all of Iran’s uranium-enrichment activities. However, there are concerns about enrichment to what is described as medium levels—near 20 percent enrichment—which provides something of a fast track to production of nuclear weapons fuel material.

More on:

This has been an area where the United States and its partners have been focused for a number of years in hopes of persuading Iran to either forgo that enrichment or to suspend and stop it. It appears that that’s an area [in which] the Iranians are at least prepared to make some initial concessions. There is discussion, at least in the reports that have come from Geneva, that Iran may be prepared to suspend that enrichment for a six-month period. Iran has been quite careful to ensure that its stockpile of this medium-enriched uranium does not go beyond what the Israelis and others have described as a red line. That is an area [where], because of the focus of many years, we’re more likely to see some quick progress. The bigger issues may be some of the technical areas of concern that have grown more urgent as Iran’s program has expanded over the course of these many years.

Like what?

In particular, the development of more sophisticated centrifuges and the heavy-water reactor based in the Iranian city of Arak, which is due to come online sometime next year. I think these are two particular issues [that] the international community is going to be looking at very closely for significant Iranian concessions in order to build up confidence that we can keep Iran significantly far from nuclear weapons capability.

There was some talk about Iran agreeing to this so-called "additional protocol" that allows UN inspectors to come in without any real warning. Can you talk about that?

This is a form of enhanced transparency, and something that has been the focus of interest for many years. The Iranians agreed to implement the "additional protocol" while Rouhani was the nuclear negotiator, but the treaty was never ratified by the Iranian parliament; and that level of transparency has not been in place in Iran for many years. And so, it is of considerable importance that Iranian negotiators appear to have said publicly that they are prepared to implement the terms of that protocol, even if they are unable for either legal or political reasons to get parliamentary ratification of the treaty addition itself. That is an important confidence builder, but, in effect, transparency is not enough.

We would like to see greater transparency and cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency from Iran. But, I believe that the more important considerations from the international community are caps on the number of centrifuges and on the extent of enrichment in Iran. While the Iranians have suggested they are prepared to talk about it, it’s not yet clear if there is any real meeting of the minds between the two sides on what kinds of numbers would be acceptable.

Of course, there are several parties who are not terribly happy about the improvement in the atmosphere. There are many members of Congress who would like to have additional sanctions put on Iran now, as well as the Israelis who are very nervous about this progress.

There are still many who have not yet been convinced that there is a real deal on the table at this point, and that’s perfectly justifiable in some quarters, given that this is a significant shift from much of what we’ve seen and heard from Iran over the course of the past eight years with former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. There are many in Congress who believe that pressure has worked, and so it should be intensified in order to ensure that we get the very best deal possible. And while I understand the logic behind that sort of an argument, I think it is a dangerous presumption to assume that simply because pressure has worked that more is always better.

In fact, it’s quite likely that if we were to see the proposed sanctions bill—which has passed the House and intended to go before the Senate over the course of the next few weeks—passed by overwhelming veto-proof majorities of the U.S. Congress, it would likely create real difficulties for the prospect of maintaining the momentum and seeing some early fruit from these talks in the form of an interim confidence-building measure, which I believe is the objective of the U.S. negotiators.

What about from the Iran side? Are there still many political prisoners that the world would like to see released?

We’ve seen a lot of progress since the election of Hassan Rouhani in June 2013, but Iran is certainly not a free and fair country. It is a country in which there are ongoing human rights abuses, including the imprisonment of many for simply participating in the political process or voicing their opinions through the media. It’s also a country with one of the highest levels of prisoner executions per capita in the world. All of these issues are ongoing concerns for the United States.

The most high-profile political prisoners in Iran today are the two candidates, Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, and their wives from the 2009 election in which Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s reelection victory was contested by millions throughout the country. The pair who had run against him and spearheaded the rejection of the official outcome has been under house arrest for two-and-a-half years under incredibly draconian circumstances. They’re in homes, not behind bars, but effectively their homes have become prisons. There are bars on the windows. They’re limited in the contact they can have with the outside world. It is truly an area that the international community ought to be focused on. There are small signs of progress even here within Iran. There has been official discussion of a review of their status, and I think that this is going to be a barometer for many Iranians, if not for the world, of how far President Rouhani can and is prepared to go in terms of changing the political climate in Iran.

And, of course, he’s constrained by what Ayatollah Khamenei will allow, right?

Rouhani is limited by the hard-liners and in the sense that he is not a reformer by any stretch of the imagination. He is very much a pragmatist who has come to this position, in a way, to lead a national unity government, to lead Iran out of the crisis that it has found itself in with the international community, and to begin to rebuild the legitimacy of the regime within Iran itself. And so he’s got a very difficult balancing act and a lot of different constituencies to try to manage as he goes about this process of moderating both at home and internationally.

What do you think will happen over the next six months? Any breakthroughs?

Predictions with Iran are incredibly dangerous, as I think you know. But I’m very optimistic. I’m not irrationally exuberant. There has been just a little bit too much adoration of the new tone that we’ve heard from Iran, and I think that it’s important to remember that we’re only beginning to see the first real tangible signs of change within the country.

But it’s quite clear that Rouhani was elected with a mission and a mandate to find some way out of the nuclear mess and rehabilitate Iran’s role in the world and fix its economy. The only way that he can do this is to come to an agreement with the international community. The negotiators and the officials that we have seen in New York and Geneva have made very clear that they are empowered, prepared, and willing. I think it’s also clear that the [Obama] administration sees the opportunity before it and is attempting to seize that opportunity.

Online Store

Online Store