How Xi Will Consolidate Power at China’s Twentieth Party Congress

At the Chinese Communist Party meeting, leader Xi Jinping will likely receive a third term. Here’s what that could mean for his control of China and the party.

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Ian JohnsonStephen A. Schwarzman Senior Fellow for China Studies

What happens at China’s party congress?

Every five years, China holds what is formally called the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party. While most decisions are made well before party congresses, the meetings matter because they’re where the Communist Party announces who will run the country for the next five years. The twentieth party congress begins on October 16.

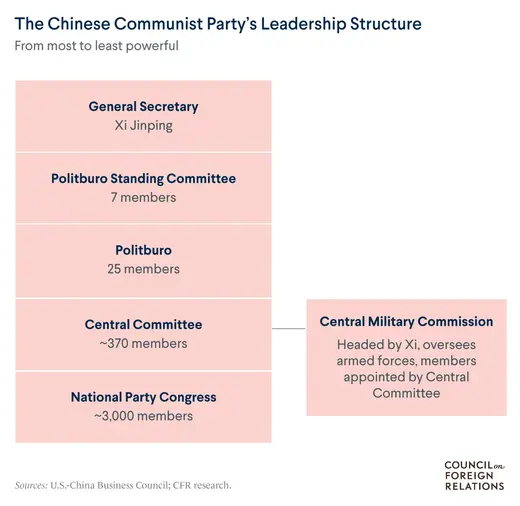

The party has more than ninety million members and is organized in pyramid-type structure. Near the top is the twenty-five-person Political Bureau, or Politburo, which is made up of military officers, provincial leaders, and central party officials. Out of this group is drawn the seven-member Politburo Standing Committee, which makes most of the crucial decisions. The head of the Standing Committee is the party’s general secretary, Xi Jinping.

At each congress, some members of the Politburo and the Politburo Standing Committee retire or are shunted aside. Some depart because they have surpassed the party’s informal age limits; most people retire by sixty-eight. Others leave for more opaque reasons, perhaps because they have not done a good job or simply aren’t in favor with the top leadership.

For about twenty-five years, the norm has been that a new general secretary is appointed at every other congress.

Xi Jinping took power in 2012, so he should be retiring this year. Why isn’t that the case?

Xi is expected to stay on for another term in his current positions as general secretary of the Communist Party, head of the party’s Central Military Commission, and president of China. His real source of power is his role as general secretary—run the party and you run China. As head of the military commission, he controls China’s armed forces. The title of president is ceremonial and makes him head of state, assuring that his visits to foreign countries are accompanied by the appropriate pomp and ceremony.

The presidency is the one position that had official term limits written into the constitution. In 2018, China’s legislature amended the constitution to lift term limits for presidents, allowing Xi to stay on. But by remaining as general secretary, Xi is breaking norms—not official rules—set by former leader Deng Xiaoping. Communist China’s founding leader, Mao Zedong, ran the country until he died in 1976. Deng, who ultimately succeeded Mao, wanted to prevent future leaders for life, so he set up an informal system in which top leaders served no longer than ten years. That was the case for Deng’s two hand-picked successors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao.

What leadership changes are expected out of the twentieth party congress?

While Xi will stay on for a third term, most members of the Standing Committee will retire. Their replacements should be announced during the congress. (Standing Committee members have always been men; the appointment of a woman would be big news.) China’s current premier, Li Keqiang, will retire in March, and it should become clear who will replace him during the meeting.

More moderate choices to replace these officials could imply the Chinese government will pursue more market-friendly policies, although it seems certain that all appointees would have to be approved by Xi and thus are not likely to vary much from his views.

What won’t be announced is Xi’s successor. So far, no one has been groomed to succeed him. The assumption is that Xi will be in power for at least this coming five-year term, and most analysts believe he will take another term after that. Assuming the party’s age limits apply to Xi’s successor and that this person would serve for ten years, a person entering the Standing Committee would have to be in their early fifties to have a shot at succeeding him. That seems unlikely given the names of the people being batted about to serve in the committee. Most are likely to be in their late fifties or early sixties, meaning they would be retiring in the next five to ten years and unlikely succeed Xi.

What does it say about the Chinese Communist Party that Xi is getting a third term?

The dominant way of looking at it in the West is that it shows Xi has crushed all opposition and wants to rule for life. That’s part of the story, but it’s also true that Xi was brought in a decade ago to make the party stronger—and he’s done that. He’s made some missteps, such as keeping the zero-COVID strategy for too long and hurting economic growth by restricting private enterprise, but he remains popular in China. Becoming party secretary isn’t a popularity contest, but it does matter.

Who opposes Xi’s third term?

Many Chinese intellectuals, writers, artists, and filmmakers, as well as a fair number of private entrepreneurs, do not like Xi. They resent his crackdown on artistic freedom, his desire to whitewash history, and his favoring state-owned enterprises over the private sector. But they have little voice in the political sphere.

Will a third term make Xi more assertive, particularly in terms of his foreign policy moves?

That is hard to say because he’s already been quite assertive. Domestically, he’s pursued a scorched-earth policy in areas with many minority populations, essentially forcing them to follow Han Chinese cultural practices. He’s also quashed civil society, reined in religious groups, and put limits on nongovernmental organizations. Internationally, he has allowed diplomats to pursue “wolf warrior” policies, which often means speaking extremely bluntly to officials in host countries; presided over a military buildup in the South China Sea; and pushed a more aggressive policy toward Hong Kong and Taiwan.

These policies have created backlash. Almost all wealthy, democratic countries—including the United States, European Union countries, Japan, and South Korea—now view China as a rival and not just an economic competitor. This has led countries to pursue policies to reduce reliance on China. This is a huge change from a little over a decade ago, when China was seen as a potential partner in the existing international order.

Today, China is instead seen as a disruptor—not on the level of Russia, which has invaded neighbors under President Vladimir Putin, but still as a serious challenge to democratic countries. That seismic shift largely took place on Xi’s watch and is almost certain to continue.

Will there be any big policy announcements during the twentieth party congress, such as economic reforms or a lifting of China’s zero-COVID policy?

Probably not. Congresses are about choosing the party’s leaders and setting its general direction. There will be a lengthy communiqué issued at the end of the meeting from which observers can glean ideas about what the government has planned. But it will mostly praise the government and list challenges.