Abenomics and the Japanese Economy

Updated

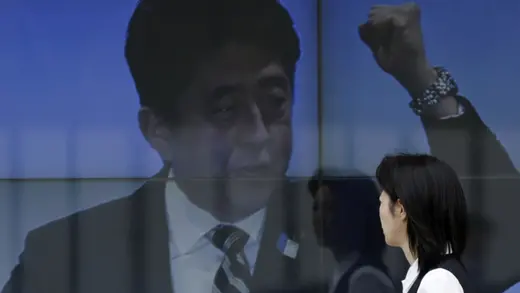

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has introduced an audacious set of economic policies designed to spur the country out of its decades-long deflationary slump. The results have so far been mixed.

Introduction

Japan, having fought deflation for more than two decades, has repeatedly pursued government interventions in the hope of revitalizing its economy. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s three-pronged approach, dubbed “Abenomics” and launched in 2013, combines fiscal expansion, monetary easing, and structural reform. Its immediate goal is to boost domestic demand and gross domestic product (GDP) growth while raising inflation to 2 percent. Abe’s structural policies aim to improve the country’s prospects by increasing competition, reforming labor markets, and expanding trade partnerships.

After four years of heavy stimulus, the country has begun to see moderate growth. But even as Abe won another term in October 2017 snap elections, growth remains tepid, inflation is below target, and concerns over debt and structural reform continue. Moreover, the election of President Donald J. Trump and the United States’ withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership have complicated Japan’s economic policymaking.

What is Abenomics?

Abenomics refers to a set of aggressive monetary and fiscal policies, combined with structural reforms, geared toward pulling Japan out of its decades-long deflationary slump. These are the policies’ “three arrows.”

- Fiscal stimulus began in 2013 with economic recovery measures [PDF] totaling 20.2 trillion yen ($210 billion), of which 10.3 trillion ($116 billion) was direct government spending. Abe’s hefty stimulus package, Japan’s second-largest ever, focused on building critical infrastructure projects, such as bridges, tunnels, and earthquake-resistant roads. A separate 5.5 trillion yen boost followed in April 2014, and after the December 2014 elections, Abe pushed through another spending package, worth 3.5 trillion yen.

- The second arrow, unorthodox monetary policy—especially the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) unprecedented asset purchase program—is at the heart of Abenomics. “It’s a gigantic experiment in monetary policy,” says the Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip. The BOJ has simultaneously injected liquidity into the economy (a policy known as quantitative easing, or QE) and, for the first time, pushed some interest rates into negative territory.

- Finally, a long-delayed program of structural reform—including slashing business regulations, liberalizing the labor market and agricultural sector, cutting corporate taxes, and increasing workforce diversity—aims to revive Japan’s competitiveness.

How does Abenomics‘ monetary policy work?

Under BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, the bank undertook an initial round of QE in 2013 that doubled its balance sheet. But with inflation stagnating below 1 percent into 2017, the bank has moved into a second, open-ended phase of QE consisting of $660 billion in yearly asset purchases that Kuroda says will continue until the 2 percent inflation target is achieved.

The scale of the purchases is unmatched anywhere in the world: the value of the assets held by the BOJ has exceeded 70 percent of GDP, while the assets of the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB), by contrast, both stand below 25 percent of their respective GDPs.

With Japan’s economy remaining weak, in January 2016 Kuroda made the unexpected decision of introducing negative interest rates in a fresh bid to spur lending and investment. The BOJ joined the central banks of the European Union, Denmark, Sweden, and Switzerland as the only ones to push some rates below the “zero bound.” The BOJ’s negative rates, as well as its asset purchases, have continued into 2018, causing some economists to warn that these low rates damage the banking system and can lead to speculative bubbles. Despite such worries, in January 2018 the bank decided to continue with a negative interest rate of minus 0.1 percent.

What are the prospects for structural reform?

Abe’s win in October 2017 elections bolstered support for his policies. But structural reform, which many analysts say will determine the success of Abenomics, still has far to go.

In 2014, Abe announced a broad reform package, including corporate tax cuts, agriculture liberalization, labor market reform, and initiatives to overhaul regulation of the energy, environmental, and health-care sectors. Although his coalition has held a strong parliamentary majority for more than five years, progress has come slowly.

Japan’s labor shortage continues to be a serious factor in its economic stagnation. The working-age Japanese population has contracted by 6 percent over the past decade, and Japan could lose more than a third of its population over the next fifty years. In September 2015, Abe announced an “Abenomics 2.0” platform that centers on raising the birth rate and expanding social security. He also created a new cabinet position dedicated to reversing Japan’s demographic decline.

The government has required corporations to increase the appointment of women to management positions.

In addition, Abe pledged to spend 2 trillion yen ($17.6 billion) on education and childcare, promising free preschool for all children aged three to five and for children aged two or younger from low-income households.

These changes partly aim to encourage more women to join the workforce, the so-called womenomics plan to raise the female employment rate from 68 percent to 73 percent by 2020. As part of this, the government has required corporations to increase the appointment of women to management positions. The original goal was to have women fill a third of senior business positions by 2020; that has since been scaled back to 15 percent.

The government argues that raising women’s wages and status in the labor market will also increase fertility rates, pointing to countries like Sweden and Denmark that have both higher female employment and higher fertility. Thus far, however, there has been little measured success in the female labor force participation rate.

Abe has also promised broader labor reforms to break down Japan’s two-tier employment system, in which a persistent class of temporary workers are shut out of the regular workforce. So far, however, his labor policy has focused on reducing the culture of overwork that has led to a rise in depression and suicides. By 2017, the unemployment rate dropped to below 3 percent for the first time in twenty-three years, signifying a tightening labor market.

What will be the impact of the U.S. withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership?

Progress on agricultural reform was central to Abe’s push to complete the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a free trade agreement with the United States and eleven other Pacific Rim countries. In 2014, he reached a breakthrough agreement to limit the power of the national agriculture cooperative, JA-Zenchu. The cooperative long used its political heft to oppose the modernization of Japan’s farming industry. The agricultural industry lobbied against TPP, contesting the removal of high tariffs and other protective measures.

Some analysts say that Trump’s rejection of TPP will complicate Abe’s economic reform efforts. With Trump reportedly seeking a bilateral U.S.-Japan trade deal in lieu of TPP, negotiations could put pressure on Abe to deliver even deeper tariff cuts and more extensive reforms in not only agriculture, but also in contentious matters such as motor vehicles and intellectual property. Thus far, Abe’s government has declined U.S. invitations to begin talks.

Meanwhile, the TPP countries minus the United States have agreed to move forward with a new version of the pact, known as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, or CPTPP. Trump has said he would consider rejoining TPP if the United States could secure a “substantially better” outcome.

Can Abenomics reinvigorate Japan’s economy?

Since Abe took power in 2012, robust GDP growth, wage growth, and inflation have all proved elusive. As of December 2017, the inflation rate was 1 percent, still significantly below the 2 percent target set as a goal in 2013. Growth has been more resilient: Japan’s GDP expanded at an annualized rate of 0.5 percent in the fourth quarter of 2017, marking eight consecutive quarters of growth for the first time in almost three decades.

One factor underpinning the recent modest economic growth is the expansion of global demand, particularly for high-tech electronics. Turning to robotics and other labor-saving technology has helped the economy combat its acute labor shortage by boosting productivity. Increased tourism and a tighter job market have also helped strengthen the national economy.

Despite this progress, policymakers see consumer spending and wage growth as disappointingly low.

Despite this progress, policymakers see consumer spending and wage growth as disappointingly low. In 2017, household spending dropped 0.1 percent and real wages decreased by 0.2 percent. Wages have fallen 9 percent in real terms since 1997. Fresh from his 2017 election victory, Abe has pushed for companies to raise pay by 3 percent in 2018, but many big corporations are reluctant to do so because of a potential loss of competitiveness and rising costs.

Most observers agree that without greater structural changes or a major demographic shift, the Japanese economy will continue to struggle. Some experts say that making it easier for immigrant workers to enter the market could boost growth, but this remains unpopular among the public.

Meanwhile, the planned reappointment of BOJ Governor Kuroda when his five-year term ends in April 2018 likely ensures that large-scale monetary easing will remain a central part of Abenomics.

What are the risks?

Critics argue that Abenomics brings major risks. Some think monetary easing could spur hyperinflation, while others contend that Abe’s plan may do too little to reverse deeply entrenched deflation. Japan’s national debt of more than one quadrillion yen ($11 trillion)—245 percent of GDP—also continues to be a cause of concern. The International Monetary Fund has repeatedly warned [PDF] that these debt levels are unsustainable.

That’s why Abe has attempted to reduce the deficit by raising taxes, a move that some say has worked at cross purposes with the rest of the program. A 2014 increase in the national consumption tax from 5 to 8 percent further depressed consumer spending and likely contributed to a renewed recession. As a result, the next planned bump, up to 10 percent, has been repeatedly postponed, first to 2017 and then to 2019.

At the same time, negative interest rates, a relatively untested monetary tool, give many economists pause. The BOJ board was split five to four on the decision over concerns that the policy could damage the banking system. Some worry that negative rates might not encourage spending, but rather the hoarding of cash, thus adding to deflationary pressures. Long-term unorthodox monetary policy may not leave Japanese policymakers with much room to absorb the shocks of future volatility in global markets, especially as the U.S. Federal Reserve and other central banks progressively raise interest rates and unwind their own QE policies.

Those who remember the trillions of dollars in spending on public works—massive and often unnecessary road and bridge construction projects—that littered Japan’s countryside during the “lost decade” of the 1990s worry that Abe’s stimulus may add to the debt load without boosting output.

What does this mean for the global economy?

Abe’s policies have been felt in the international arena. Exporters such as Germany and China have sounded warnings about a global currency war, or competitive devaluation, in which countries vie to weaken their currencies to gain an advantage for their exports, given that Abe’s policies have indirectly weakened the yen.

Tokyo’s recent disputes with Beijing over the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands in the East China Sea have spilled over into their economic relationship, and the yen’s drop has only escalated the discord. Abe’s hawkish reputation, along with his push to amend Japan’s pacifist constitution, has led some to see his TPP trade push as a way to contain Beijing.

The election of Trump, who brings a new vision of global trade and economic policy oriented away from the multilateral negotiations favored by President Barack Obama, has complicated Abe’s options. Some experts have argued that Trump’s rejection of TPP and his criticism of Japanese trade practices could unsettle the U.S.-Japan alliance, a relationship that Abe has called “the cornerstone of Japanese foreign policy.” Trump has also heavily criticized what he calls Japan’s currency manipulation, accusing Abenomics of “playing the devaluation market,” a charge that Abe strenuously denied.

The outcome of Japan’s experiment also holds implications for other economies, including the eurozone, that are also struggling with deflation and low growth. “Almost the entire rich world is stuck in a zero-interest-rate liquidity trap situation, and I think everybody is haunted by the possibility that there’s no way out of it,” says Ip. “If Japan shows a way out of that, it will be very encouraging.”

Camilla Siazon contributed to this report.

Recommended Resources

This August 2016 IMF country report [PDF] discusses Japan’s hopes for economic recovery.

The Congressional Research Service discusses the major elements of the Trans-Pacific Partnership in this 2016 report [PDF].

This 2014 Congressional Research Service analysis [PDF] explores the rationale behind “womenomics.”

BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda discusses the challenges of overcoming deflation and Japan’s economic policy in this CFR meeting.

In this Foreign Affairs essay, Richard Katz critiques the implementation of Abenomics.

This April 2013 Economist article appraises Abenomics.t

Colophon

Staff Writers

- James McBride

- Beina Xu

Additional Reporting

Header image by Ints Kalnins/Reuters.