Inequality and Tax Rates: A Global Comparison

Published

With economic inequality at an all-time high, some U.S. presidential candidates are proposing dramatic shifts to the U.S. tax code. How have similar plans worked elsewhere in the world?

As the 2020 campaign for the presidency of the United States gets underway, candidates have announced a raft of new tax proposals, including increases in the top marginal income tax rate, the creation of a broad wealth tax, and reversing recent cuts to the U.S. estate tax. All three proposals are what economists term “progressive” taxes, meaning they would fall most heavily on wealthier taxpayers, in contrast with “regressive” taxes, which more directly affect lower-income citizens.

Proponents say these measures would address economic inequality, pointing to the United States’ position as one of the most unequal countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a grouping of industrialized democracies. Opponents, however, say that such proposals would stifle growth and hobble economic innovation. They also argue that the experiences of other wealthy countries show a mixed record for similar policies.

The Debate Over Inequality

In the past decade, economists and policymakers have raised concerns over the economic and political implications of rising inequality, renewing debate over the role of government in redistributing wealth. Former President Barack Obama called it “the defining issue of our time,” and Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz has claimed inequality diminishes young voters’ belief in markets and eventually leads to weaker growth [PDF]. In the United States, inequality has deepened in the past half century, especially since the 1990s. The OECD listed the United States as its fourth-most-unequal member in 2014, the latest year with data from all members, trailing only Costa Rica, Mexico, and Turkey.

Many in the United States have taken the view that addressing this inequality should not be a central aim of government, and that lower taxes spark economic growth, improve productivity, and make everyone better off. In 2017, President Donald J. Trump signed major tax legislation that reduced many federal tax rates, most notably the top rate levied on corporations, which went down from 35 percent to 21 percent and which members of both major parties had long argued hurt American competitiveness. It also lowered individual income taxes, especially for higher earners, bringing the top marginal income tax rate down from 39.6 percent to 37 percent.

At 26 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP), the overall U.S. tax haul is near the bottom of OECD countries.

These cuts have been targeted by many Democratic presidential candidates ahead of the 2020 election who call for higher taxes on the wealthy. They cite not only rising inequality but also growing fiscal deficits and national debt that could threaten popular federal spending programs. This is a concern because the United States takes in much less tax revenue as a proportion of the overall economy than its peers: At 26 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP), the overall U.S. tax haul is near the bottom of OECD countries. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the 2017 tax reform will result in $1 trillion less revenue [PDF] over the following decade.

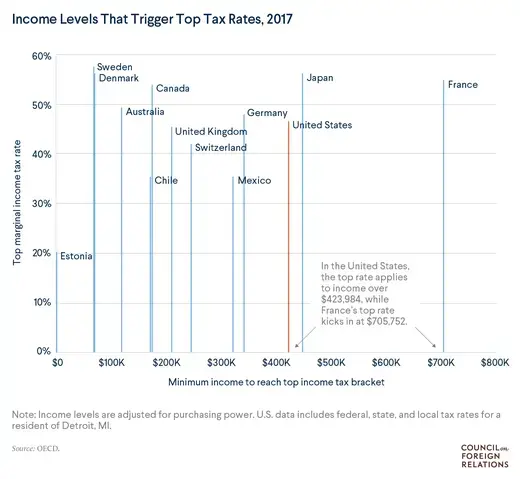

Some of these proposals have been tried by other wealthy democracies, but comparisons provide a cloudy picture. While many have higher rates than the United States, the taxes are often less progressive, falling more heavily on the middle or upper middle classes, rather than only the richest individuals.

Raising Income Tax Rates

Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) kicked off the chorus for higher taxes in January 2019, when she called for a 70 percent marginal tax rate on annual income above $10 million. Presidential candidates such as former housing secretary Julian Castro and Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) have embraced Ocasio-Cortez’s plan.

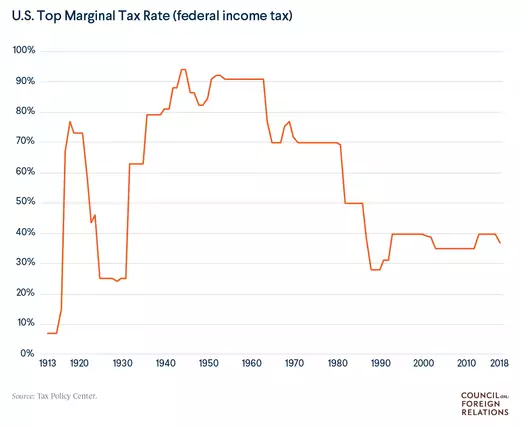

Her proposal draws on a 2011 paper [PDF] by MIT economist Peter Diamond and University of California economist Emmanuel Saez that suggested 73 percent would be the optimal top income tax rate—maximizing U.S. government revenue without deterring additional economic growth. They point out that top income tax rates in the United States were significantly higher for much of the U.S. postwar period, while the American economy boomed. As recently as 1963, the top income tax rate exceeded 90 percent. Political opponents and some economists claim such rates will deter new businesses and say that the high rates of previous eras wouldn’t increase government revenue by as much as predicted because it is now easier for citizens to hide their earnings and report less income.

As recently as 1963, the top income tax rate exceeded 90 percent.

Several advanced economies have top income tax rates well above the current U.S. rate. Sweden, often cited as the most progressive tax regime in the OECD, maintains a top statutory income tax rate of 57.1 percent. The rate kicks in for citizens earning more than one and half times the average income, which comes out to about $70,000 in Sweden, a much lower threshold than current U.S. proposals. Other advanced economies have slightly lower top rates that still stand above the American average: Japan (55.9 percent), France (54.5 percent), and Canada (53.5 percent), for example. It should be noted that the top U.S. rate of 37 percent does not factor in state and local taxes, which vary across the country.

Some countries have experimented with even higher rates similar to what Ocasio-Cortez proposed. After his 2012 election, French President Francois Hollande implemented a “super tax” of 75 percent for salaries above $1.3 million. Hollande withdrew it in 2015 after drops in investment caused revenues to fall, which some commentators suggested was in part due to the tax making France a less attractive investment destination. Some employers reached informal arrangements to keep employees’ salaries artificially low and then compensate them once the tax was removed, shrinking the income base for tax collections.

Levying Wealth Taxes

Another Democratic proposal is a tax on accumulated wealth, meaning the total value of assets held by U.S. households, rather than on yearly income. It is an approach championed by Senator Warren, who proposes taxing wealth in excess of $50 million at 2 percent per year. Wealth above $1 billion would face an additional 1 percent tax. This proposal, originally developed by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman [PDF] of the University of California, Berkeley, would apply to seventy-five thousand households and would raise some $2.8 trillion over a decade—more than making up for the tax cuts passed in 2017.

The logic behind such a tax is that the richest Americans don’t derive most of their worth from income, but rather keep it invested in businesses, stocks, real estate, and other assets whose value can appreciate over time. Saez and Zucman join other economists, most notably the French economist Thomas Piketty, who view wealth taxes as the best way to reverse a dramatic worldwide increase in wealth concentration that has accelerated since the 1980s. Piketty’s 2013 book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, argued that economic returns to assets outpaced the overall rate of economic growth, ensuring that inequality will continue to widen over time if wealth is left untaxed; others disagree.

There are many arguments against a wealth tax. Some critics oppose the tax on constitutional grounds, and even advocates admit it would be challenged in court. Then there are logistical concerns: it would require significant resources to determine amounts owed to the government and ensure compliance. Some wealthy individuals may even renounce their citizenship to avoid the tax. Additionally, economic concerns persist. Some economists said a 2014 proposal by Piketty would reduce investment, employment, and overall output, and a 2010 study [PDF] of OECD countries’ wealth taxes from 1980–1999 by researchers at Sweden’s Lund University found “robust support for the contention that taxes on wealth dampen economic growth.”

Few OECD countries take this approach. While ten did at the turn of the century, today only Switzerland, Norway, and Spain maintain net wealth taxes. Some such as France and the United States tax property, which is a form of wealth tax that falls on the less wealthy. Wealth taxes in both Norway and Switzerland are lower than Warren’s proposal for the United States but they apply to a broader swath of the population. Norway, for instance, applies a tax of 0.85 percent on all net wealth above $178,000—a low enough threshold that most small-business owners must pay it.

Increasing Inheritance Taxes

The U.S. inheritance tax, applied to large estates that get passed down to an heir, has existed since 1916, but the proportion of residents who pay it has shrunk over time. Between 2001 and 2017, the cutoff for individuals increased from estates valued at $650,000 to those over $11 million. The recent tax reform again raised the qualifying threshold: It now stands at $11.2 million for individuals or $22.4 million for married couples, with rates for amounts above the threshold ranging from 8 to 40 percent, depending on the total value of the estate. This applies to 0.2 percent of U.S. estates, and it is expected to generate $250 billion in revenue over the next decade.

These taxes have long been unpopular, but Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT), a presidential hopeful, has proposed a substantial hike. He suggests applying a top rate of 77 percent—last reached in the 1970s—on estates worth more than $1 billion, and rates of at least 45 percent on estates valued above $3.5 million. Sanders says his plan would raise up to $315 billion over a decade.

The U.S. trend toward lower inheritance taxes is in line with other OECD countries, where “the proportion of total government revenues raised by such taxes has fallen by three-fifths since the 1960s,” the Economist points out. Sweden repealed its inheritance tax in 2004 after several high-profile Swedish entrepreneurs emigrated to avoid it. Australia, Canada, and Norway have all abolished their own in the past half century. Some outliers persist: Japan applies its estate tax more often than any other OECD member, raising $20 billion annually from taxing estates valued above $270,000. Japan’s top marginal rate is 55 percent, above the current 40 percent in the United States and United Kingdom but below Senator Sanders’s proposed 77 percent.

Alternative Proposals

There are several other approaches to reforming taxation that either have been proposed in the United States or are in use in other OECD countries.

Higher capital gains taxes. Taxpayers who sell assets for a profit must pay a capital gains tax on that profit. The current top federal rate for this tax is 20 percent, compared with the top income tax rate of 37 percent. Despite this gap, U.S. capital gains rates are actually in line with many other OECD countries, with a few exceptions. Denmark’s top marginal capital gains tax rate is 42 percent, for example. Some experts say discrepancies between taxes on capital gains and income contribute to increasing inequality and they suggest raising capital gains taxes, perhaps up to income tax levels.

Much lower taxes. Free market advocates argue that taxation meant to address inequality can, perversely, stunt growth and make everyone worse off. They say that higher taxes on the rich deter entrepreneurs from taking the risks that made them successful in the first place. Some maintain that tax cuts pay for themselves by spurring growth so much that overall tax revenue increases.

While most other wealthy democracies collect more tax revenue, proportionately, than the United States, there are a handful of exceptions. Chile’s tax collection, for example, amounts to some 20 percent of its GDP, below the U.S. tax take of 26 percent. (The country joins Ireland, Mexico, South Korea, and Turkey as the only OECD countries with lower tax revenue rates than the United States.) Chile’s low level of taxation stems from its 1973–1990 military dictatorship, which, advised by economists trained at American universities (the so-called Chicago Boys), slashed taxes and privatized state-owned industries.

Chile eventually emerged as just the second country in South America to reach the World Bank’s high-income bracket. “These successes, based on years of consistent and often rapid economic growth, have made Chile into a model for Latin American success,” writes CFR’s Shannon K. O’Neil. Yet inequality has begun to chafe at Chilean society, leading to nationwide protests against the widest gap between rich and poor among OECD members.

Flat taxes. Some politicians, such as Senators Ted Cruz (R-TX) and Rand Paul (R-KY), have proposed making the federal income tax a flat tax, rather than a progressively graduated tax. Under these plans, all income—regardless of how high or low—would be taxed at a constant rate. Cruz proposed a 10 percent rate, while Paul proposed 14.5 percent. Critics point out that flat taxes are regressive, but advocates tout their ability to simplify the U.S. tax code. A handful of OECD countries, mostly former Communist states, have flat income tax rates: the Czech Republic (15 percent), Estonia (20 percent), Hungary (15 percent), and Latvia (23 percent). Estonia’s system in particular has won plaudits from conservative economists for attracting investment while maintaining an overall tax haul in line with other OECD countries.

Consumption taxes. The United States is an outlier as the only OECD member without a value-added tax (VAT), a consumption tax charged on the increase in value at each step of producing a product. Such taxes are among the most regressive form of taxation because those with less income spend a larger portion of that income on consumer goods. Economists tend to favor them because they see them as less distortionary and harder to evade than taxes on income or investment, though most U.S. politicians have so far avoided backing what would amount to a tax hike on the poor and middle class. Meanwhile, other OECD countries rely on VATs to raise the higher amounts of tax revenue they need to fund their generous welfare states: Denmark, Norway, and Sweden levy 25 percent VATs; Hungary’s is higher still at 27 percent; and even low-tax Chile maintains a 19 percent VAT.

Recommended Resources

The OECD publishes the annual tax revenues of all member countries, going back to 1965.

Bloomberg compiled opinion pieces on taxes and inequality in February 2019.

Our World in Data charts the history of taxation around the world.

The Tax Policy Center walks readers through the complexities of the U.S. tax system.t

Colophon

Staff Writers

- Andrew Chatzky

Additional Reporting

Header image by Jonathan Ernst/Reuters.