South Korea’s Chaebol Challenge

Published

South Korea’s megaconglomerates have helped lift the country out of poverty, but their extraordinary influence could put the health of the Korean economy at risk.

Introduction

A group of massive, mostly family-run business conglomerates, called chaebol, dominates South Korea’s economy and wields extraordinary influence over its politics. These powerful entities played a central role in transforming what was once a humble agrarian market into one of the world’s largest economies.

The South Korean government has generously supported the chaebol since the early 1960s, nurturing internationally recognized brands such as Samsung and Hyundai. However, in recent years chaebol have come under fire amid a slowing South Korean economy and following a series of high-profile corruption scandals, including one that prompted mass protests and the ouster of Park Geun-hye.

What is a chaebol?

The word chaebol is a combination of the Korean words chae (wealth) and bol (clan or clique). South Korea’s chaebol are family-owned businesses that typically have subsidiaries across diverse industries.

Traditionally, the chaebol corporate structure places members of the founding family in ownership or management positions, allowing them to maintain control over affiliates. Chaebol have relied on close cooperation with the government for their success: decades of support in the form of subsidies, loans, and tax incentives helped them become pillars of the South Korean economy.

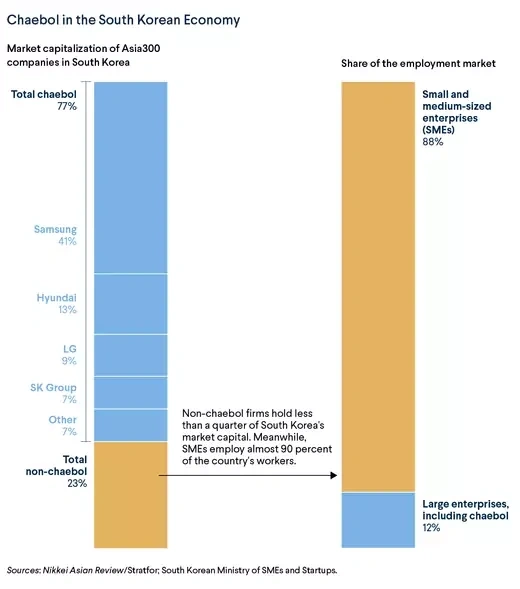

Although more than forty conglomerates fit the definition of a chaebol, just a handful wield tremendous economic might. The top five, taken together, represent approximately half of the South Korean stock market’s value. Chaebol drive the majority of South Korea’s investment in research and development and employ people around the world. Samsung Electronics, the largest Samsung affiliate, employs more than 300,000 people globally (more than Apple’s 123,000 and Google’s 88,000 combined).

Which are the largest chaebol?

Samsung. Founded in 1938, Samsung Group is South Korea’s most profitable chaebol, but it began as a small company that exported goods, such as fruit, dried fish, and noodles, primarily to China. Today the conglomerate is run by second- and third-generation members of the Lee family, the second-wealthiest family in Asia, according to Forbes. Over the past eighty years, the company has diversified to include electronics, insurance, ships, luxury hotels, hospitals, an amusement park, and an affiliated university. Its largest and most recognized subsidiary is Samsung Electronics, which for the past decade has accounted for more than 14 percent of South Korea’s gross domestic product (GDP).

Hyundai. Hyundai Group was a small construction business when it opened in 1947 but grew immensely to have dozens of subsidiaries across the automotive, shipbuilding, financial, and electronics industries. In 2003, following the Asian financial crisis and the death of its founder, Chung Ju-yung, the chaebol broke up into five distinct firms. Among the standout offshoots are Hyundai Motor Group, the third-largest carmaker in the world, and Hyundai Heavy Industries, the world’s largest shipbuilding company.

SK Group. The conglomerate, also known as SK Holdings, dates back to the early 1950s, when the Chey family acquired Sunkyong Textiles. Today, the chaebol oversees around eighty subsidiaries, which operate primarily in the energy, chemical, financial, shipping, insurance, and construction industries. It is best known for SK Telecom, the largest wireless carrier in South Korea, and its semiconductor company, SK Hynix, the world’s second-largest maker of memory chips.

LG. LG Corporation, which derives its name from the merger of Lucky with GoldStar, got its start in 1947 in the chemical and plastics industries. Since the 1960s, the company, under the direction of the Koo family, has heavily invested in the development of consumer electronics, telecommunications networks, and power generation, as well as its chemical business, which includes cosmetics and household goods. In 2005, LG split, spinning off a separate entity called GS, a chaebol whose core businesses are in energy, retail, sports, and construction.

Lotte. Shin Kyuk-ho founded Lotte Group in Tokyo in 1948 and brought the chewing gum company to South Korea in 1967. The conglomerate’s main businesses are concentrated in food products, discount and department stores, hotels, and theme parks and entertainment, as well as finance, construction, energy, and electronics. Lotte Confectionery is the third-largest gum manufacturer in the world. In 2017, the company opened the Lotte World Tower in Seoul, the tallest building in South Korea, with 123 stories.

How did chaebol emerge?

Many of South Korea’s chaebol date to the period of Japanese occupation before the end of World War II, modeling themselves after Japan’s powerful industrial and financial conglomerates, known as zaibatsu. As U.S. and international aid flowed into Seoul [PDF] following the Korean War (1950–1953), the government provided hundreds of millions of dollars in special loans and other financial support to chaebol as part of a concerted effort to rebuild the economy, especially critical industries, such as construction, chemicals, oil, and steel.

Park sought to build a South Korea that was self-reliant.

Scott A. Snyder, Council on Foreign Relations

These enterprises flourished under the leadership of General Park Chung-hee, who led a military coup in 1961 and then served as president from 1963 to 1979. As part of Park’s export-driven development strategy, his authoritarian government prioritized preferential loans to export businesses and insulated domestic industries from external competition. The practice was similar to that of the other Asian tigers, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore. “Park sought to build a South Korea that was self-reliant and not dependent on great powers for its security,” writes CFR’s Scott A. Snyder in his 2018 book, South Korea at the Crossroads.

Over time, the chaebol expanded into new industrial sectors and tapped into lucrative foreign markets, providing more fuel for South Korea’s engine. Exports grew from just 4 percent of GDP in 1961 to more than 40 percent by 2016, one of the highest rates globally. Over roughly the same period, the average income of South Koreans rose from $120 per year to more than $27,000 in today’s dollars. As South Korea lifted millions out of poverty, the parallel rise of chaebol embedded the conglomerates into the narrative of South Korea’s postwar rejuvenation.

How did democratization and the 1997 financial crisis impact them?

South Korea’s democratic transition in the late 1980s had important but limited effects on the chaebol system. Democratization fostered the formation of strong labor unions, which fought for higher wages, better working conditions, and an unraveling of the close relationship between the government and chaebol. Reforms in the early 1990s introduced nominal improvements in economic governance and paved the way for South Korea to join the World Trade Organization and the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development. However, throughout this period, the nexus between government and big business remained largely unchanged.

On the other hand, the 1997 Asian financial crisis, in which countries across the region were hit by plummeting currencies, debt crises, and recessions, tested South Korea’s chaebol-dominated economic model. In the lead-up to the crisis, South Korean banks lent aggressively to chaebol so they could expand into new sectors. Before and after the exchange rate crisis hit, fifteen of the top thirty conglomerates [PDF] were allowed to go bankrupt.

In December 1997, South Korea agreed to a more than $50 billion international bailout package, a record amount at the time. As a condition of the rescue, led by the International Monetary Fund, Seoul instituted reforms intended to weaken the chaebol system, including new corporate transparency measures and cuts to government subsidies. More broadly, the bailout required major economic adjustments: reducing government deficits, restructuring insolvent financial institutions, and liberalizing trade and foreign investment.

How close are chaebol to the government?

The South Korean government and the chaebol have long had a symbiotic relationship. Many leaders in Seoul have equated the success of the chaebol with South Korea’s postwar prosperity. “The large conglomerates and Korean economy cannot be separated from the politics and the culture and history,” says Rhyu Sang-young, a professor at Yonsei University in Seoul.

The large conglomerates and Korean economy cannot be separated from the politics and the culture and history.

Rhyu Sang-young, Yonsei University

Today, some politicians look to chaebol for financial support during campaigns and often tout chaebol economic successes as national ones. Meanwhile, the chaebol lobby for favorable legislation and public policy. Critics say the tight-knit relationship between Seoul and the chaebol has fostered a culture of corruption, in which embezzlement, bribery, and tax evasion have become the standard. “Asking for money from chaebol executives in return for political favors was considered quite normal until very recently,” Kang Won-taek, a professor at Seoul National University, told the Economist.

The cozy relationship between chaebol and government has increasingly roused the public’s ire. In recent decades, South Korea’s economic growth has dropped from near double digits to around 3 percent, while chaebol have gone global and moved many jobs overseas. Chaebol, once seen as instruments of growth, have become financiers for the government and “contributed more to Korean social inequality than to society,” says CFR’s Snyder.

Many top executives have been found guilty of corruption, including leaders from Samsung, Hyundai , Lotte, and SK. Despite their convictions, the businessmen rarely see the inside of a prison for long, if at all; many pay heavy fines instead, receive presidential pardons, or see their jail sentences suspended by the courts.

Public discontent with the chaebol reached a new peak in 2016–17 with the eruption of a massive influence-peddling scandal that led to the ouster of President Park Geun-hye. In April 2018, she was sentenced to twenty-four years in prison and fined almost $17 million for soliciting bribes from many of South Korea’s top chaebol. In a separate investigation, Park’s predecessor, Lee Myung-bak, was arrested in March 2018 on a slew of graft charges, for which he could receive a life sentence.

What are the ongoing challenges with chaebol?

Despite the scandals, chaebol have continued to stack their corporate boards with allies and place new generations of family in executive roles. While the boards generally adhere to international standards of transparency, analysts say that in practice chaebol families continue to dominate from the sidelines and have fostered a cult of personality that prioritizes loyalty. Practices such as cross-shareholding, in which families exert control over chaebol through a web of circular investments in various affiliates, persist.

Though the chaebol are responsible for the majority of the country’s investment in research and development, experts say they may also introduce challenges to the health of the Korean economy. Economists have warned that the behemoth conglomerates often use their monopolistic clout to squeeze small and medium enterprises (SMEs) out of the market, often copying their innovations rather than developing their own or buying out the SMEs. In this predatory environment, SMEs, which provide for most of the country’s employment, are unable to grow.

There is also a significant wage gap, as the average pay for workers at SMEs is only 63 percent of that at chaebol. South Korea faces growing income inequality levels [PDF] and limited job growth, with high youth unemployment rates.

Further, experts say that large-scale corruption, often associated with the chaebol, reduces economic competitiveness, diminishes social trust, leads to wasteful spending and poor decision-making, and sometimes necessitates large bailouts.

What’s the debate over reforming the chaebol system?

Many experts say the South Korean economy will require major corporate governance reforms to create sustainable growth and limit inequality.

The government, particularly under liberal administrations, has implemented some policies to change corporate management and ownership structures, increased transparency for management and financial reporting, and consolidated chaebol business ventures in core areas. However, analysts say reforms have so far only tackled low-hanging fruit. Chaebol remain dominant, with the top ten owning more than a quarter of all business assets in the country.

Elected in May 2017, President Moon Jae-in came into power with a mandate to sever the government-chaebol nexus and crack down on corruption. He has vowed to end the practice of pardoning convicted executives, raised the minimum wage, and modestly boosted the corporate tax rate from 22 to 25 percent. However, his ability to enact reforms is undermined by his party’s lack of a majority in parliament, where chaebol hold sway over many members.

Some economists have suggested other policy changes, including tougher antitrust laws, a ban on all cross-shareholding among subsidiaries, and greater voice to minority shareholders, to finally break the dominance of the chaebol. Yet many experts caution that changing the chaebol system’s deeply entrenched culture will not happen overnight.

Recommended Resources

CFR’s Scott A. Snyder traces South Korean foreign policy and U.S.-South Korea relations in his 2018 book, South Korea at the Crossroads.

Bloomberg breaks down the status of South Korea’s chaebol.

Alice Amsden examines South Korea’s industrialization in her 1992 book, Asia’s Next Giant.

Hank Morris explores the mounting economic challenges for both the young and old in South Korea.

Min Byung-seong of Griffith University looks at what the Park sentencing means for South Korea’s economy.

CFR’s Snyder tracks the unfolding of the Park scandal.

Peter S. Kim analyzes Moon’s reform agenda for South Korea’s chaebol system.t

Colophon

Staff Writers

- Eleanor Albert

Additional Reporting

Header image by Kim Hong-ji/Reuters.