China’s May Reserves

The change in China’s headline reserves is actually one of the least reliable indicators of China’s true intervention in the foreign currency market. Valuation changes create a lot of noise. And it is always possible for China to intervene in ways that do not show up in headline reserves. Last fall, for example, much of the intervention came from changes in the banks’ required foreign currency reserves.

The change in the foreign assets on the PBOC’s balance sheet, and the State Administration on Foreign Exchange’s (SAFE) foreign exchange settlement data are more useful.

More on:

Still, there is valuable information in today’s release. The roughly $30 billion fall in reserves to $3,192 billion (not a very big sum) is more or less explained by a $20 billion or so fall in the market value of China’s euros, yen, pounds, and other currency holdings. Actual sales appear to have remained low.

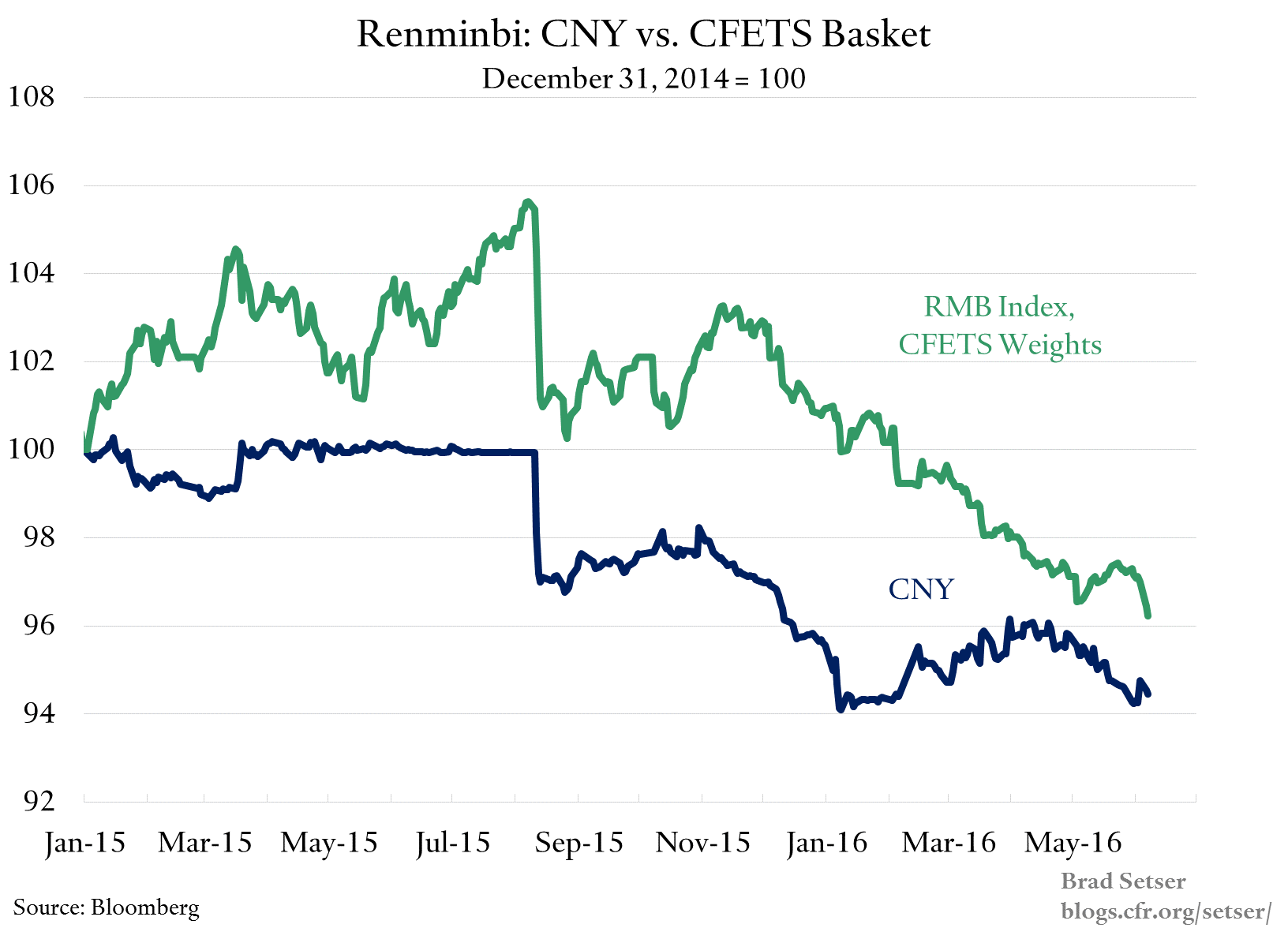

That is interesting and perhaps a bit surprising, as the yuan depreciated in May against the dollar. And in past months, yuan depreciation against the dollar has been associated with large sales of dollars, and strong pressure on the currency.

We need the full data on China—the "proxies" for true intervention that should be released over the next couple of weeks—to get a complete picture. But if it is confirmed that China’s reserve sales were indeed modest, I can think of three possible explanations:

1) Renewed enforcement of controls on the financial account are working. They limited outflows.

More on:

2) Chinese companies have mostly finished hedging their foreign currency debts. They now have had three quarters to pay it down, or to hedge. And it certainly seems from the balance of payments data in late 2015 that Chinese banks and firms were paying back their cross-border loans with some speed.

3) Managing against a basket (at least some of the time) is working. The depreciation against the dollar came in the context of the yuan’s appreciation against the basket, and thus did not generate expectations that the move against the dollar was the first step in a much bigger devaluation.

Of course, China runs an ongoing goods trade surplus—one that brings in roughly $50 billion a month. That helps keep the market balanced even with large outflows.

There is always the possibility that intervention is being masked, and pressure on headline reserves was reduced by the sale of foreign currency by state banks and state firms. And, well, the Chinese authorities rather clearly allowed the yuan to slide against the basket when the dollar sold off on the U.S. jobs number. Since January, the trend against the basket has been down.

But at least in May, and looking at only one of the relevant data points, it does not on first glance appear that the yuan’s slide against the dollar significantly destabilized expectations.

Still worth watching closely.

Online Store

Online Store