Estimated Chinese Intervention in April

Chinese reserves appear to be stable over last three months.

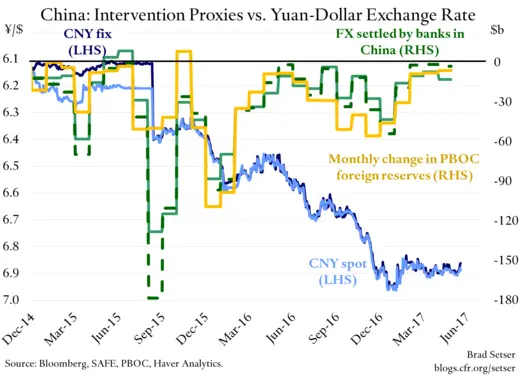

The best proxies for Chinese intervention for April are now out. The PBOC balance sheet data suggests China sold about $6 billion in April, and the FX settlement data, adjusted for forwards, shows $2 billion in sales.

Settlement includes the state banks—it isn’t just the PBOC. But historically it has been one of the most reliable indicators of China’s “true” intervention. The “headline” settlement number shows $12 billion of sales. But the net forward position (forward sales of dollars) fell by $10 billion.

The settlement numbers, net of the change in forwards, illustrate just how little China has had to sell on net to keep its exchange rate stable over the past few months. Average monthly sales over the last three months, adjusted for the change in the forward book, are in the very low single digits.

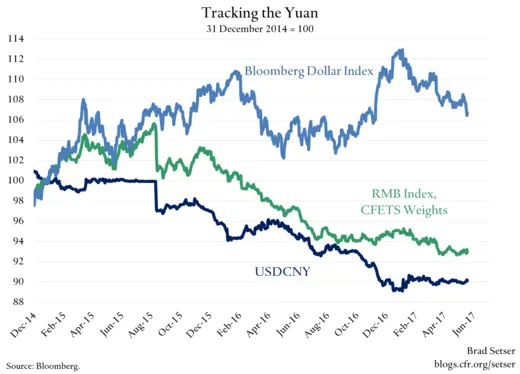

Stability in the yuan’s exchange rate against the dollar has brought stability in China’s reserves. There is no longer an expectation China wants a weaker currency. China’s controls no doubt have helped too. And Trump’s relatively soft line on trade with China likely has reduced the risk that China might respond to aggressive unilateral action by allowing the yuan to slide.

So far this year, the yuan has moved by less against the dollar than against the basket. That at least raises the possibility that China operationally is putting more weight on stability against the dollar than stability against the basket. If so it is critical that the link to the dollar be symmetric—the yuan has to go up with the dollar, not just down against the dollar.

Cameron Crise though has noted that there isn’t a clear cut case that China operationally is prioritizing stability against the dollar: realized volatility has been lower against the basket than against the dollar.

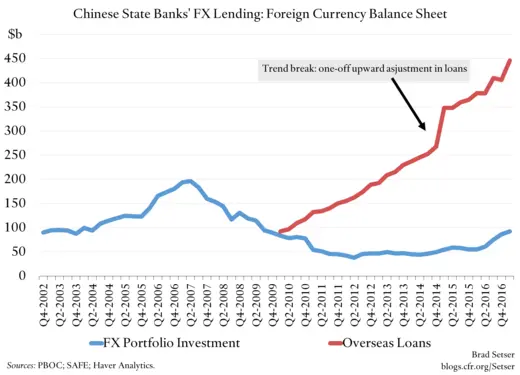

There is one other thing to note—one that matters in light of China’s commitment to provide $100 billion in financing (not all in dollars, a significant portion will be in yuan, and thus likely used to pay for imports from China) to One Belt One Road. Throughout 2016, even when China was selling its reserves early and late in the year, its state banks added significantly to their foreign assets.

And that continued in the first quarter of this year. With reserve sales down (the fall in reserves in the balance of payments in the first quarter was only $2 billion, though other indicators show larger q1 sales) it is possible that China’s state, on net. added to its total foreign portfolio. Think flat reserves, but rising offshore loans and an increase in the banks holdings of foreign debt securities.*

The PBOC publishes data on the aggregate foreign currency balance sheet of the state banks. I think the China Development Bank (CDB) is included in the total** but not Export-Import Bank of China. Please correct me if this is off. The foreign currency balance shneet shows the state banks hold foreign assets of just over $550 billion—with a significant rise in 2016. The net international investment position data lags a bit and isn’t available for q1, but it shows a similar rise in 2016.

Jane Perlez and Keith Bradsher of the New York Times report that China so far has provided about $50 billion of financing through the policy banks and the New Silk Road fund to support One Belt One Road. Those funds were provided over four years, which works out to $10-15 billion a year—far less than the overall pace of increase in the total external lending of China’s state banks over the state time period. The additional $120 billion or so ($50 billion in yuan) committed to the project should imply a somewhat faster pace of loan growth (though perhaps less funding for other projects and countries, such as Venezuela?) but nothing that would need to be wildly out of line with the general increase in China’s overseas lending portfolio over the last five or so years.

Bottom line: Right now, my best guess is that the Chinese state has returned to its “traditional” position and is accumulating assets abroad—not selling them. The difference being that China is now accumulating assets through the state banks and their overseas lending rather than through the central banks’ balance sheet.

Among other things, that makes exchange rate surveillance a bit harder. Direct central bank intervention isn’t the only action that the state can take that influences the exchange rate. Channeling funds abroad through the policy banks has a similar effect.***

* Technically the domestic balance sheet data here is holdings of securities denominated in foreign currency. But the balance of payments data shows a parallel rise in Chinese resident’s holdings of foreign bonds.

** It is now long forgotten but there was a time when the CDB wanted to be more “commercial” prior to the crisis—it was thinking of trying to buy equity in foreign banks. The inclusion of the CDB would help explain the steady growth in total offshore loans in the data.

*** So long as the banks aren’t funding themselves by also borrowing from abroad. The net increase in the banks’ foreign asset position is what matters for the exchange rate. (Setting hedging aside for the moment).