A Bit More on Chinese, Belgian and Saudi Custodial Holdings

Marc Chandler asked why I chose to attribute Belgium’s holdings to China rather than any of the other potential candidates—notably the Gulf and Russia.

The answer for Russia is pretty straightforward. Russia’s holdings of Treasuries (and in the past Russia’s holdings of both Treasuries and Agencies) tend to show up in the U.S. custodial data. Russia holds around $275 billion in securities in its reserves, and it holds a relatively low share of its reserves in dollars (40 percent still?). $85 billion in Treasuries (in March) is more or less in line with expectations. There are maybe a few billion missing, but there also is no need to search for large quantities of missing Russian dollar-denominated reserve assets.

Differentiating between the Gulf and China is a bit harder. Both are to a degree “missing” in the custodial data. Both China’s and the Gulf’s custodial holdings are a bit lower than would be expected based on the size of their reserves, and for the Gulf, the size of their reserves and sovereign fund. Both are big players, so both could conceivably account for one of the key features of Belgium: the rapid rise and then the rapid fall in Belgian’s custodial holdings.

So why China?

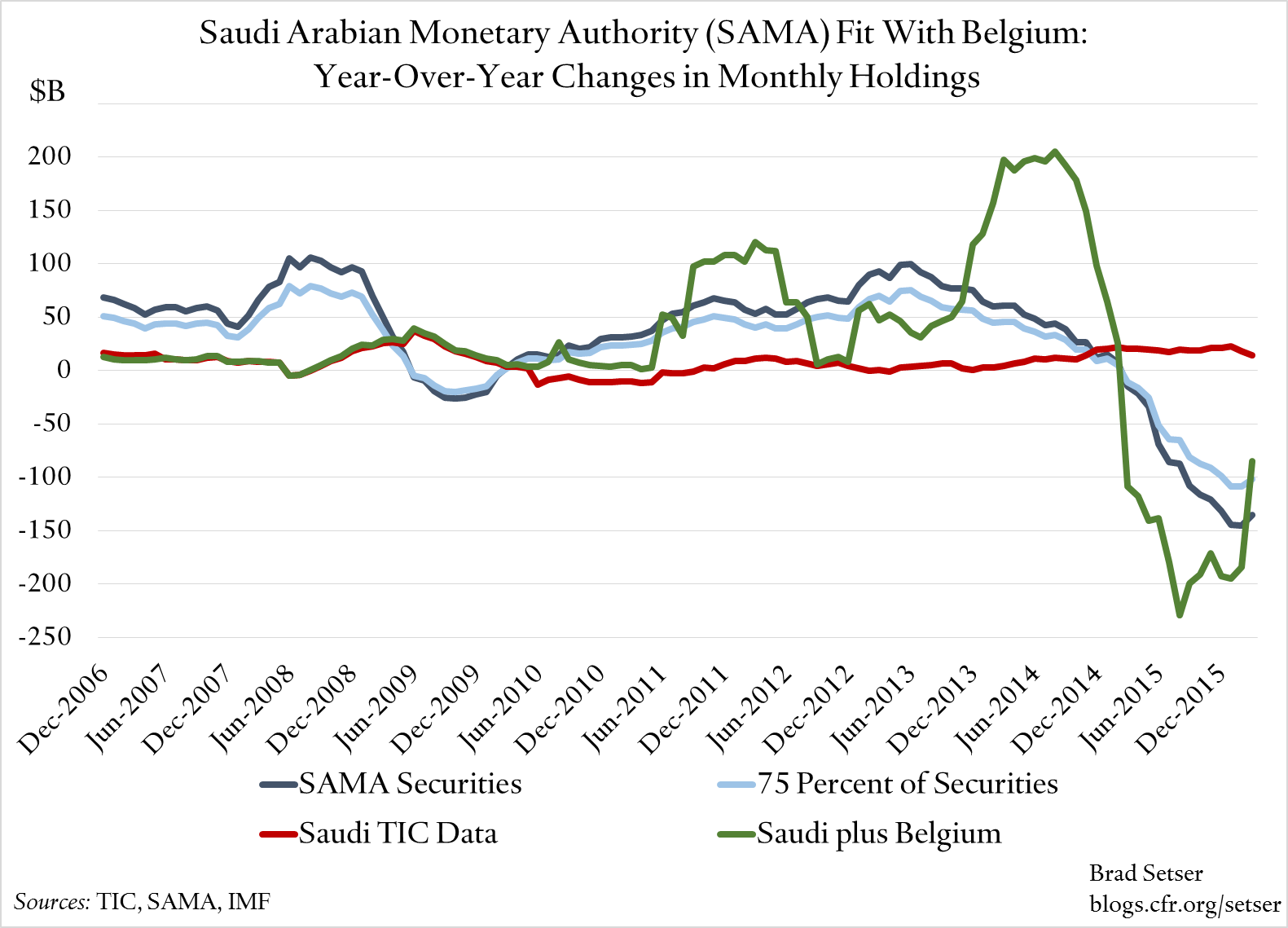

Consider a plot of Saudi Reserves—looking only at the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency’s (SAMA) holdings of securities. I also plotted the change that would be expected if say 75 percent of SAMA’s securities were in dollars, just as a reminder that the full change is the upper limit. SAMA also has a lot of deposits, but they aren’t relevant here.

It is fairly clear that the changes in Belgium’s custodial holdings are a loose fit at best for SAMA’s security holdings. The big run-up in the Belgian account actually came when the pace of Saudi reserve growth was slowing. And the drawdown in Saudi reserves started a bit before the drawdown in Belgium, and has been more steady.

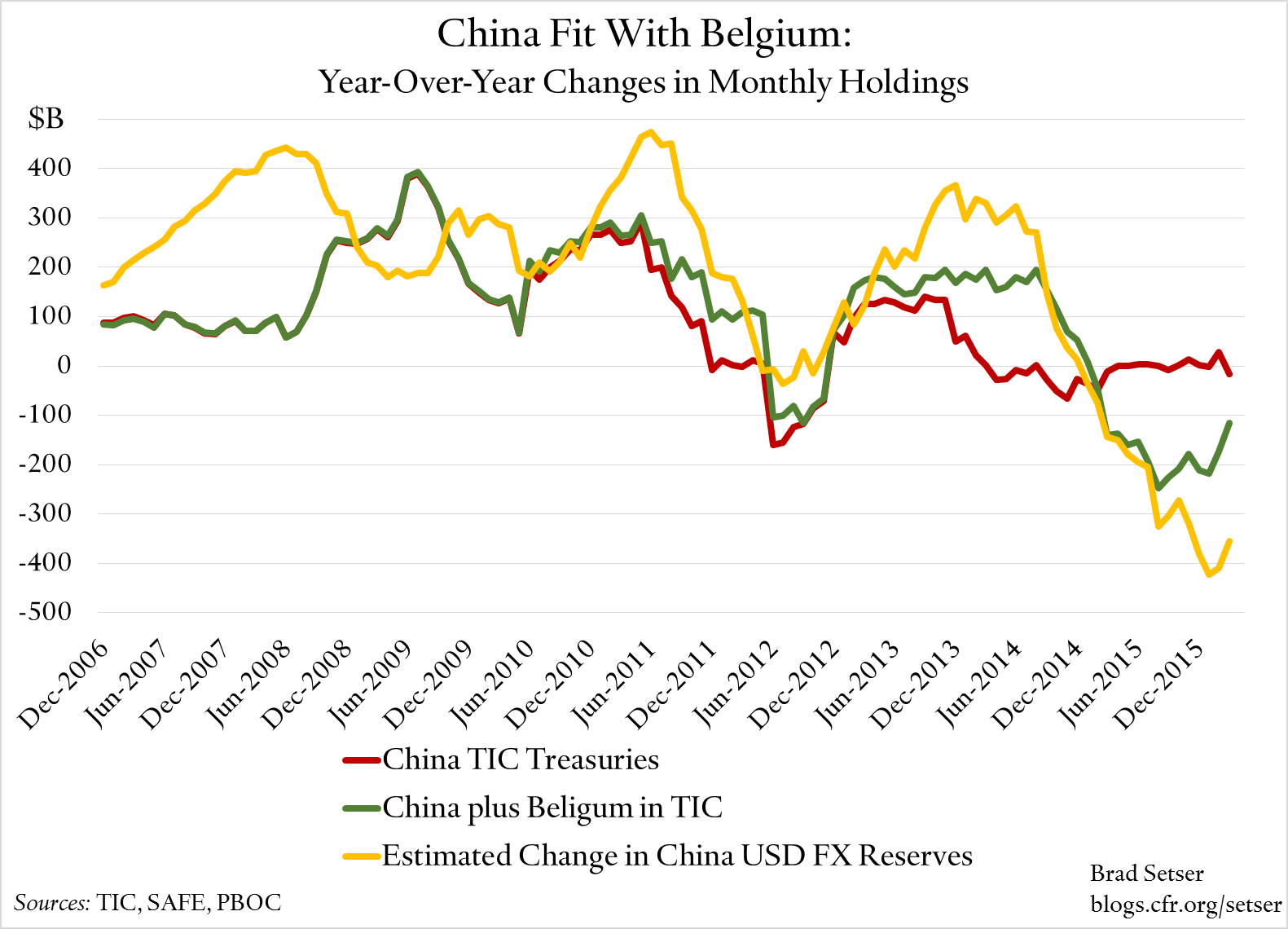

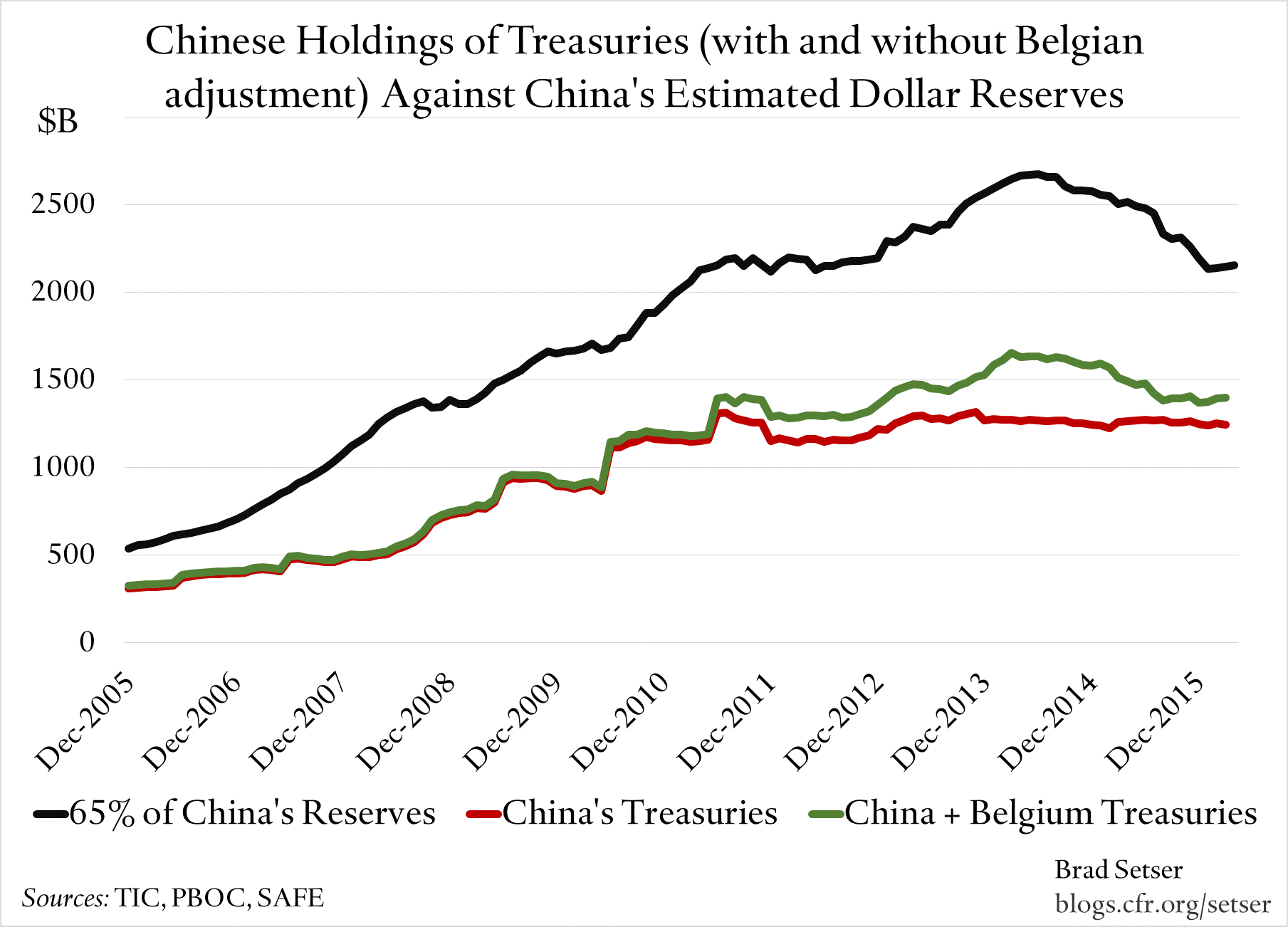

Now consider a plot of changes in Belgium’s holdings against estimated changes in China’s dollar reserves (including all reserves throws off the scale), assuming a roughly 65 percent dollar share of reserves. Adding the change in Belgium’s holdings to the change in China’s holdings significantly improves the fit over the last four years.

This is not proof of course. But it provides the basis for my adjustment.*

If you plot China and Belgium’s combined holdings against China’s estimated dollar reserves, the overall fit is reasonable. The change in Belgium occurs at the right time and is of the right magnitude to match a thesis that the Chinese have kept the Treasury share of their reserves constant, and the Treasury share of their dollar reserves constant.

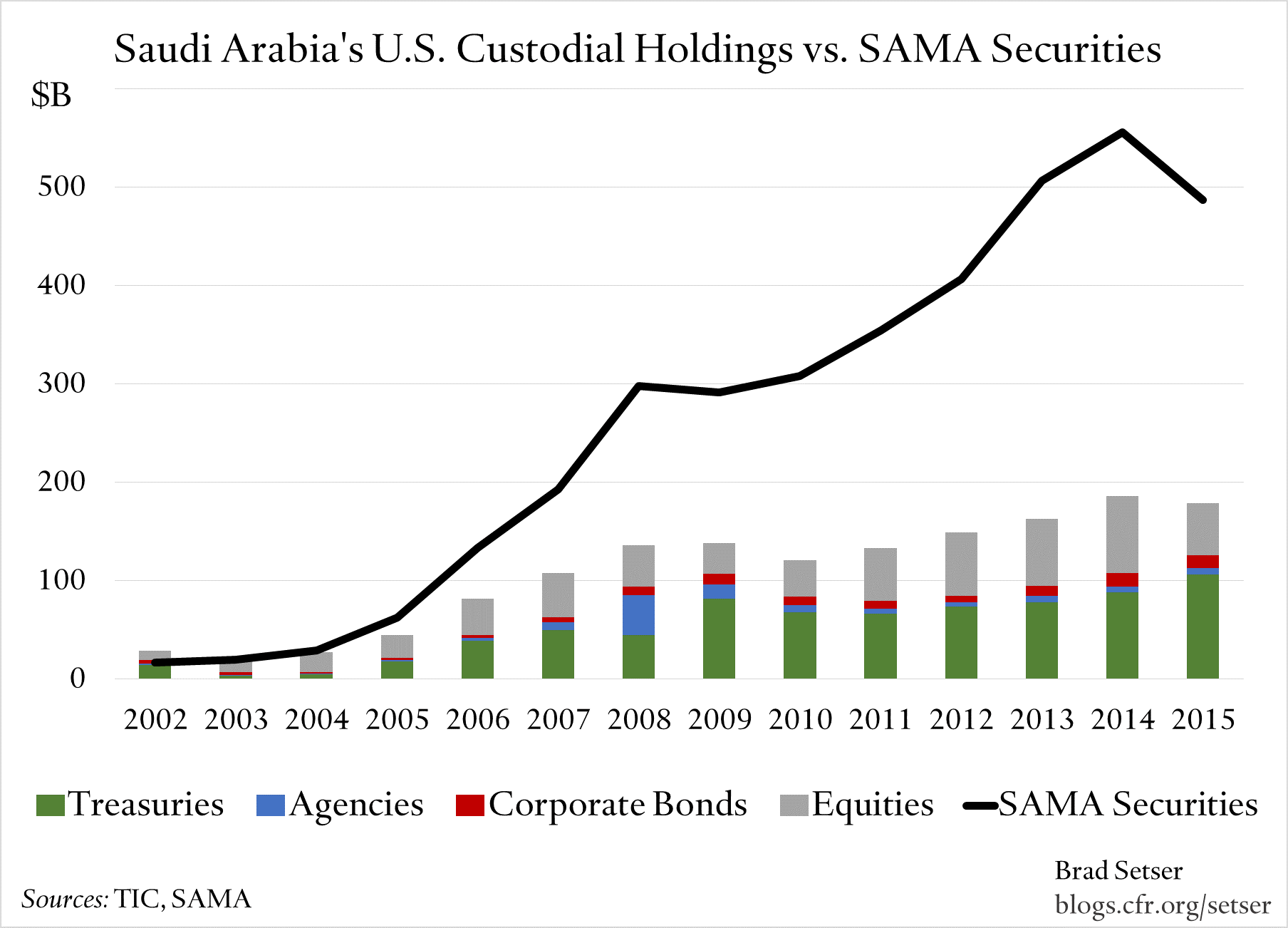

Incidentally, the Treasury has released past “survey” data for all of the Gulf countries. The Saudis do hold a decent amount of U.S. equities—$52 billion last June. But Kuwait and the Emirates—with their large sovereign funds—hold more. Kuwait had just over $135 billion. No surprise there.

A plot of the Saudi’s custodial holdings of all U.S. bonds and equities against SAMA’s holdings of securities in its reserves over time is still interesting. The Saudis, it seems, joined the Chinese and Russians in piling into Agencies just before the global crisis (quietly adding to the pressure to recapitalize them?).

And even if all the Saudi assets in the TIC data, including the equities, are assumed to come from SAMA and even if deposits are left out of the analysis, there is a bit of a gap between the Saudi TIC holdings and what you might expect. Private fund managers? European custodial accounts (there are options other than Belgium)? Fancy financial engineering?

Wealthy Saudis also of course have a global investment portfolio: back in 2002, Saudi’s total holdings in the U.S. data exceeded SAMA’s reserves. But Saudi private assets are even less less likely than SAMA to register cleanly in even the new and improved U.S. data.

One last point: thanks to Concentrated Ambiguity , we now know the best answer to Dan Drezner’s question “where are Saudi’s reserves” is in “dollar-denominated bank deposits in London.”

The heavy concentration of bank deposits in dollars make sense. The Saudis do peg to the dollar after all. London isn’t exactly a surprise either.

* I also erred on the side of simplicity, in part to make my estimates for China easy to verify. Adding Belgium’s long-term holdings of Treasuries to China’s is more straightforward than estimating China’s share of total Treasuries in Belgium, Luxembourg and Switzerland, excluding the Swiss National Bank’s estimated Treasury holdings. The goal is to produce the best possible estimate with the fewest possible adjustments. But it is ultimately a judgement, one subject to constant revision.