Campaign Foreign Policy Roundup: Election 2020 Is Almost Over, Maybe

The finish line is in sight. Some 1,190 days after little-known Maryland Congressman John Delaney became the first major party candidate to formally announce a run for president, and after more than $13 billion has been spent trying to persuade voters, Election 2020 is almost over. Next Tuesday is Election Day and the counting begins. Here are five observations on what lies ahead.

1. A lot is at stake.

You don’t have to agree with Republican partisans that the United States will go socialist if Joe Biden wins or with Democratic partisans that America’s two-century-plus experiment with democracy will end if Donald Trump wins to think that this is a pivotal election. The two candidates offer different visions for the United States, have different personalities, and favor different management styles. On foreign policy, their policy solutions diverge even where they agree on the problem at hand, as on China, Afghanistan, and trade. In short, a second Trump term would take the United States in a different direction than a first Biden term, and vice versa. But next Tuesday’s vote isn’t just about who will sit in the Oval Office. It’s also about who will control the U.S. House and Senate, and who will control state governorships and legislatures. The latter are of unappreciated importance. The United States is about to undertake its decennial reapportionment of congressional seats. In most states it will be state legislators and governors drawing—or gerrymandering—those district maps. So Election 2020 will be the gift that keeps on giving—at least for a decade—for the party that comes out on top next Tuesday.

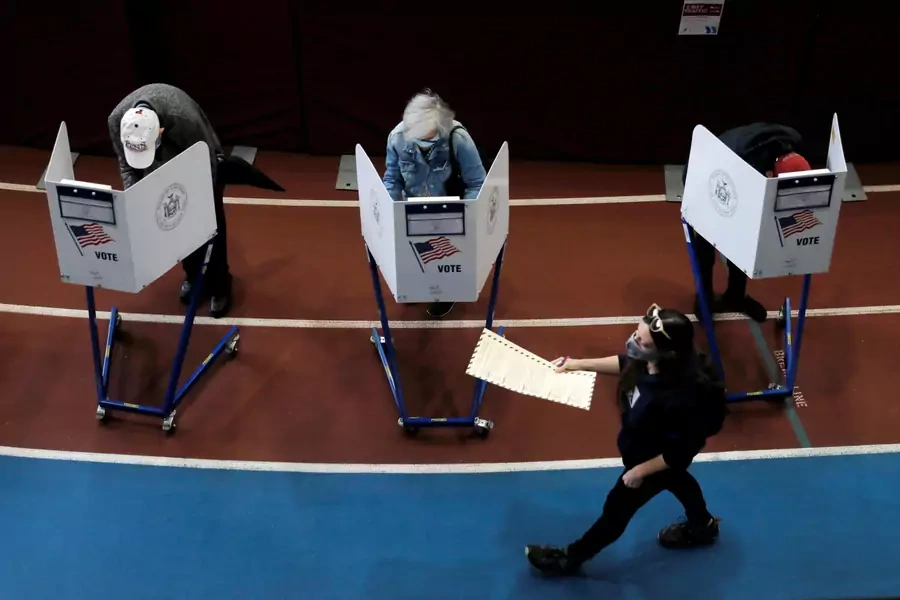

2. Americans are voting like it.

More on:

Not too long ago it looked like American voters were losing interest in presidential politics. In 1996, voter turnout fell below 50 percent for the first time in history. Even in 2008, during the midst of the Great Recession, turnout hit just 57 percent—and that was the highest turnout in forty years. Well, turnout in 2020 will likely top 60 percent—a level not seen since 1968—and it could even become the highest turnout recorded in more than one hundred years. As of this morning, more than 85 million Americans had already cast their ballots. That’s more than 61 percent of all the ballots cast in 2016. (These numbers will be even higher by the time you read this.) The surge in voting carries with it one potential downside, however. If Trump replicates his 2016 feat of winning the Electoral College while losing the popular vote, the difference in the popular-vote totals could be substantially larger than the 2.9 million votes in 2016. That’s true even if the percentage of vote shares don’t change at all, and polls show that Biden’s lead is more than three times Hillary Clinton’s final margin. An election in which the winning candidate received, say, four or five million votes less than the losing candidate would fuel growing concerns that the United States has become a country subject to minority, rather than majority, rule.

3. We might know the winner on Election Night.

The airwaves and internet have been consumed with speculation that the United States may go days if not weeks before a winner is known because so many ballots are being cast by mail. Trump himself has championed the idea that something will be wrong if a winner is not known on Election Night. Of course, Americans old enough to remember 2000 know that the Republic can survive a prolonged election count—George W. Bush didn’t win the presidency until December 12, five weeks after the polls closed. But for all the handwringing about vote counting next week, it’s possible that we may know the winner fairly quickly. Trump won the presidency narrowly, and he’s now in a dogfight in many of the states he won comfortably four years ago. The most notable such state is Florida, which is relatively efficient at handling mail-in ballots. The Sunshine State expects to announce mail-in and early ballot totals shortly after the final polls close at 8:00 p.m. EDT. Assuming that public opinion surveys are at least remotely accurate, if Biden wins Florida—or Georgia or North Carolina for that matter—Trump will have an exceedingly narrow pathway to victory in the Electoral College, if he has one at all.

4. Then again, we might not.

The prospect of a prolonged ballot count becomes far more likely if Trump holds serve in the states he won four years ago. Attention will then shift to the three industrial states that were pivotal in 2016—Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. The laws in all three states bar election officials from validating ballots, let alone counting them, before Election Day. Given how many mail-in ballots each state has received, that will take time. Pennsylvania’s secretary of the commonwealth expects that “the overwhelming majority” of the state’s mail-in votes will be counted by next Friday. But that count could be delayed or hamstrung by legal challenges. That’s especially true if all the speculation about a “red mirage” (or “blue shift”) proves correct and Trump builds a substantial lead as in-person votes are counted on Election Night, only to see that lead shrink, if not evaporate, as states count mail-in ballots. Those have been cast disproportionately by Democrats. Keep in mind, however, that these scenarios depend upon Trump having a sizable lead on Election Night. If the in-person vote isn’t lopsided, the incentives to turn to the courts and the consequences of doing so both diminish.

5. Don’t expect the U.S. House to decide who the next president will be.

Barton Gellman created a stir last month with an Atlantic article noting that disputes over who won a state’s electors could force the 2020 election into the U.S. House of Representatives. It’s worth noting that the House has chosen the president only twice in U.S. history, and the last time was 196 years ago. (The Senate would choose the vice president in such a scenario, and yes, it could make the losing presidential candidate’s running mate the vice president.) In making a decision, individual House members would not cast votes. Instead, each state delegation would cast one vote. (Washington, DC, which has three Electoral College votes, has no say in a contested election because it does not have voting representation in the House.) That vote presumably would be determined by which party holds a majority of the delegation. So the party that controls the most state delegations when the new Congress is seated on January 3 would have the upper hand. (Republicans currently hold a twenty-six to twenty-three edge in state delegations, with one state delegation tied, even though Democrats currently hold a thirty-five-seat edge in the House overall.) If state delegations are equally divided, then a stalemate is possible. In that situation, Trump’s term would end at noon on January 20—that is specified in the U.S. Constitution. The presidency would then presumably go to the Speaker of the House under the terms of the Presidential Succession Act. But even that is not assured. Yes, all this can make your head spin. But again, it’s not likely to happen.

Whatever result Election Day produces, it won’t heal the deep partisan divide that now grips the United States. It may actually aggravate it. A new article in the journal Science finds that Democrats and Republicans have moved from disagreeing on the issues to abhorring one another, a process that has created a strain of “political sectarianism.” That mutual detestation can be seen in a recent poll that found that four in ten supporters of both Biden and Trump said they will not accept the election outcome if their candidate loses. So one side or the other will be deeply unhappy no matter what unfolds next week.

More on:

The Candidates in Their Own Words

Trump announced a deal last Friday to normalize relations between Israel and Sudan. Days earlier, he removed Sudan from the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism and promised to “ensure that it is fully integrated into the international community.” The president signaled that more good news would be coming: “So we have many countries, as you know, getting ready. And we also have—I’m sure you’ll see Saudi Arabia in there very soon.”

In a “60 Minutes” interview, Leslie Stahl asked Trump who the United States’ biggest foreign adversary is. He answered, “I would say China. They’re an adversary. They’re a competitor. They’re a foe in many ways, but they’re an adversary. I think what happened was disgraceful. It should never have happened. They should never have allowed this plague to get out of China and go throughout the world. 188 countries. It should never have happened.”

In a separate “60 Minutes” interview, Norah O’Donnell asked Biden what he thought was “the biggest foreign threat that America faces.” He responded:

Our lack of standing in the world. Look what he does. He embraces every dictator in sight, and he pokes his finger in the eye of all of our friends. And so what's happening now is you have—you have the situation in Korea where they have more lethal missiles and they have more capacity than they had before.

O’Donnell was clearly looking for the former vice president to name a country, so she asked, “Which country is the biggest threat to America?” Biden answered:

Well, I think the biggest threat to America right now in terms of breaking up our—our security and our alliances is Russia. Secondly, I think that the biggest competitor is China. And depending on how we handle that will determine whether we're competitors or we end up being in a more serious competition relating to force.

Biden released two foreign policy statements this week. One called for sanctions to pressure President Alexander Lukashenko to step down in Belarus:

Although President Trump refuses to speak out on their behalf, I continue to stand with the people of Belarus and support their democratic aspirations. I also condemn the appalling human rights abuses committed by the Lukashenka regime.

The other statement called for intensified U.S. efforts to mediate the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh:

While he [Trump] brags about his deal-making skills at campaign rallies, Trump has yet to get involved personally to stop this war…The United States should be leading a diplomatic effort to end the fighting, together with our European partners, and push for international humanitarian assistance to end the suffering; under my administration that is exactly what we will do.

In an op-ed that was likely intended to court Indian American voters, Biden wrote that he has always valued the U.S.-India relationship: “We’ll open markets and grow the middle class in both the United States and India, and confront other international challenges together, like climate change, global health, transnational terrorism and nuclear proliferation.” Biden’s pitch to Indian American voters is no doubt helped by the fact that his running mate, Kamala Harris, is of Indian descent.

What the Pundits Are Saying

Secretary Madeleine Albright and Richard Haass discussed the global challenges awaiting the next president. They agreed that dealing with the coronavirus, China, and climate change will top his inbox.

The CFR podcast Why It Matters explored why U.S. voter turnout is so much lower than in most other advanced industrial democracies.

My colleague Steven Cook reviewed the Trump administration’s Middle East policy and concluded that it has been a “failure.” Despite a few successes, “the problem with Trump’s approach to the Middle East is not actually inconsistency but rather the scattershot quality of his encounters with the region.”

My colleague Michelle Gavin wrote that Trump’s “appallingly careless statement” this week that Egypt could blow up the controversial Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam “is indicative of a larger problem” of U.S. policy toward Africa during the Trump administration.

My colleagues Benn Steil and Benjamin Della Rocca found that the relief payments the Trump administration has provided to farmers as compensation for the harm done to them by the trade war with China amount to 92 percent of the revenues generated by the tariffs Trump imposed when he initiated that trade war. So not only have American importers had to pay $66 billion in new taxes—“tariff” is just a fancy name for a tax on imported goods—U.S. taxpayers have had to shell out $61 billion to offset the losses U.S. farmers have suffered from a trade war that was supposed to be “good, and easy to win.”

That’s not the only news on the economic front. Tony Newmeyer reviewed Trump’s pledge to revitalize the Rust Belt and discovered that “he hasn’t delivered.” Indeed, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, the three Rust Belt states that Trump won in 2016, “are suffering more severe economic strain than the rest of the country.” Meanwhile, Bob Tita and William Mauldin examined the impact of President Trump’s tariffs on imported steel and found that “the tariffs haven’t produced the steelmaking renaissance and robust job growth in America’s industrial heartland that Mr. Trump promised.” And Josh Zumbrun and Bob Davis assessed trade data and concluded that “President Trump’s trade war against China didn’t achieve the central objective of reversing a U.S. decline in manufacturing.”

Lionel Barber wrote that Trump’s legacy of a transactional and assertive foreign-policy approach to Asia is “likely to endure” even if Biden wins.

Joanne Lu summarized what Trump and Biden have said on a range of foreign-policy issues, including foreign aid, refugees, and reproductive rights.

Christian Paz wrote that the “Biden Doctrine begins with Latin America,” saying that Biden may leverage his existing relationships in the region to showcase the United States’ return to multilateralism and leadership.

In the second installment of their assessment of Trump’s foreign policy, Tom McTague and Peter Nicholas concluded that “in seeking to exhibit strength, Trump has made America weaker.”

Campaign Update

RealClearPolitics’ average of national election polls has Biden leading Trump by 7.8 percentage points, 51.3 percent to 43.5 percent. Biden’s lead was 7.9 points last week. FiveThirtyEight estimates that Biden has an 89 percent chance of winning based on current trends, two points higher than last week.

If you want to explore the details of vote counting, the New York Times created a list of when state officials expect to report election results and which type of ballots (mail-in or in-person) will be tabulated and released first.

The Supreme Court was busy this week, possibly foreshadowing an even busier docket next week. On Monday, it voted 5-3 against allowing an extension of Wisconsin’s mail-in ballot deadline past Election Day. Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote a concurring opinion that was not, ahem, well received, either by fellow Associate Justice Elena Kagan or a lot of other legal scholars, and not just because it contained a glaring factual error. But on Wednesday the Court turned down a request from Pennsylvania Republicans for an expedited decision that could have overturned a ruling by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court that extended the deadline for mail-in ballots to be received to three days after Election Day. The Court also declined to overturn a decision by North Carolina’s state board of elections to count ballots received up to nine days after Election Day, provided that they are postmarked no later than November 3. New Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett did not participate in any of these three cases.

Election Day is just four days away.

Margaret Gach, Kara Jackson, and Anna Shortridge assisted in the preparation of this post.

Online Store

Online Store