Central banks aren’t always a stabilizing presence in the market

More on:

Over the last couple of years it was often asserted that sovereign investors -- due to their long time horizons -- tend to be a stabilizing presence in markets that they invest in. The argument was generally made about sovereign funds, but it presumably applied at least in part to central banks as well. They have a somewhat shorter time horizon than most sovereign funds, but they also presumably care a bit more about financial stability.

Alas, there is now one clear case where an abrupt shift in central bank purchases destabilized a market.

Central banks stopped buying Agency bonds in August and never resumed their purchases. The US Treasury now says that Agency bonds are "effectively" guaranteed -- and they certainly have more Treasury backing than in the past. But that wasn’t enough to convince the world’s central banks. They now want nothing less than a full guarantee.

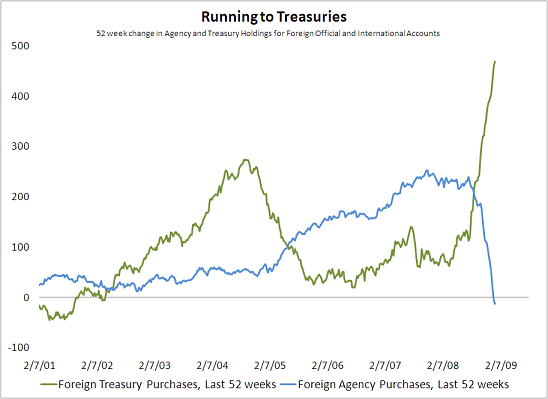

The latest (year-end) data from the New York Fed on foreign central banks’ custodial holdings shows that the magnitude of the shift out of Agencies and into Treasuries in the later part of the year. Central banks went from buying $250-300b of Agencies a year (judging from the growth of their FRBNY portfolio) to net sellers of Agencies in a rather short period of time.

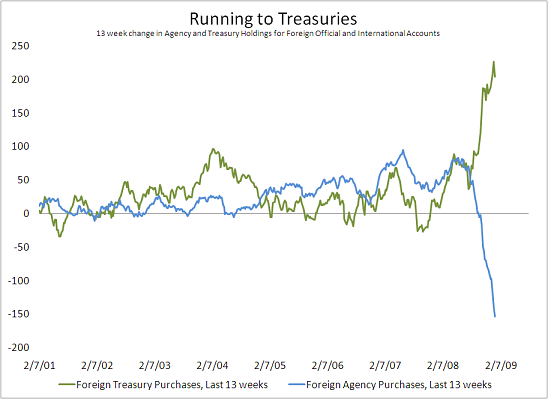

The 3 month (proxied by the 13 week) change, in billions of dollars, in the Fed’s custodial holdings is even more dramatic in some ways. It leaves no doubt that central banks have been large sellers of Agencies. The Fed’s custodial holdings of Treasuries rose by $250 billion over the last three months of 2008 while the Fed’s custodial holdings of Agencies fell by $150 billion. Try annualizing these numbers. In the fourth quarter, central banks were buying Treasuries at a $1 trillion annual pace and selling Agencies at a $600 billion annual pace.

It seems hard to argue against the proposition that a sudden increase in central bank’s risk aversion has contributed to the distress in a key part of the US market.

Central bank reserve managers’ core concern, of course, isn’t stabilizing the US debt market. It is making sure that they have enough liquid assets to meet their own country’s liquidity needs. It used to also be to make a bit of profit on the country’s-- before it swung to making sure that they didn’t take credit losses. The net result, though, was a lot of pressure on the Agency market in the fourth quarter -- and a lot of central bank demand for Treasuries just when private demand for Treasuries also soared. Suddenly risk adverse reserve managers sold what was cheap and bought what was dear, magnifying rather than dampening market moves.

This experience should also to some way toward settling another debate: are central banks’ purchases and sales big enough to impact prices in large, liquid markets?

Many argued that the Treasury market was so deep and so liquid that it could absorb even large central bank sales without too much trouble. Central banks (net) purchases were large relative to the Treasury’s (net) sales, but they weren’t that large relative to total Treasury market turnover. That led many to argue that if central bank sales ever pushed a bond away from its fundamental value, private buyers would step in -- preventing any large move in price.*

The Agency market isn’t a perfect analogue to the Treasury market. But it is quite large -- the outstanding stock of Fannie and Freddie bonds (counting Fannie and Freddie guaranteed MBS) is over $5 trillion. Agency issues aren’t quite as homogenous as Treasury issues, but they don’t differ that much from each other either. Both Freddie and Fannie have lots of outstanding bonds in the market -- and, at least until recently, the Agency market was also considered to be fairly liquid. It still doesn’t seem to have been able to absorb the big swing in central bank demand.

Agency spreads widened significantly when central banks pulled back (the expansion in the supply of debt with an implicit if not explicit guarantee also played a role ...). They only came back in when the Fed indicated it would start buying Agencies ...

And it sure seems like the enormous increase in central bank demand for Treasuries is one -- though certainly not the only -- reason why Treasury yields are so low right now. The obvious risk here is that the US government will infer too much from the fact that Treasury yields collapsed even as Treasury issuance soared. The current surge in central bank demand for Treasuries is unlikely to be sustained, if for no other reason than global reserve growth has slowed and central banks have a finite supply of Agencies to sell. I personally think this risk is manageable, as I expect a meaningful rise in US savings (an a fall in investment) will free up domestic funds for the Treasury (or start to flow into the banks, allowed the Fed to scale back its loans to the banks and scale up its Treasury holdings). But it is a risk.

In one key respect though, central banks have remained a stabilizing force: they abandoned the Agency market, not the dollar market. This underscores an important point, one that I wish I had recognized earlier. Central bank reserve managers can influence the US market in two very different ways:

a) By shifting out of one asset and into another asset. Selling Agencies and buying Treasuries for example. Or selling equities to buy Treasuries.

b) By shifting out of the dollar

A country like China that is effectively pegged to the dollar can shift the composition of its US portfolio around without putting much pressure on the dollar or its peg. Moving from Agencies to Treasuries is consequently a fairly low cost option for China. Sure, China gives up a bit of yield. But it doesn’t have to abandon its exchange rate regime. It is an option that China can exercise at a low cost to itself.

Moving away from the dollar, by contrast, would require adjustment in China - not just adjustment in the US ... and that hasn’t been something that China has been willing to do.

NOTE: I replaced by initial charts -- which used the monthly data -- with charts that show the 52 week and 13 week change in the custodial holdings. Thanks to Paul Swartz for help with the more detailed charts.

* The argument could also be made in reverse. If central bank purchases drove a bond’s price up too much, private investors would sell -- so the bond’s price (and yield) wouldn’t move away from its "fundamental" value. That led some to argue that central bank purchases couldn’t have much of an impact on say the Treasury market.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store