CFIUS Reform: Not a Solution, But a Start

Reforming the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States does not guarantee the United States will maintain its technological advantage over China.

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Guest Blogger for Net Politics

Alexandra Kilroy is an intern in the Digital and Cyberspace Policy program at the Council on Foreign Relations.

As Chinese firms pour funds into promising Silicon Valley start-ups, many national security experts are concerned that China may soon surpass the United States as a technological power, in part though investing in U.S. firms and acquiring cutting-edge technology. The United States should impose more stringent regulations on foreign investment to maintain control over vital industries and ensure that homegrown advancements are not snatched up by eager adversaries, though a successful long term strategy will require the US to invest more at home.

A committee already exists to review foreign investments in important areas of the economy. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) is the interagency body responsible for reviewing mergers, acquisitions, and takeovers by foreign entities. It is chaired by the Secretary of Treasury and is made up of voting members representing the Departments of Homeland Security, State, and Commerce, among others. If CFIUS determines that a transaction poses national security risks, it can impose requirements on the deal to mitigate risk or refer the transaction to the president, who has the authority to block it.

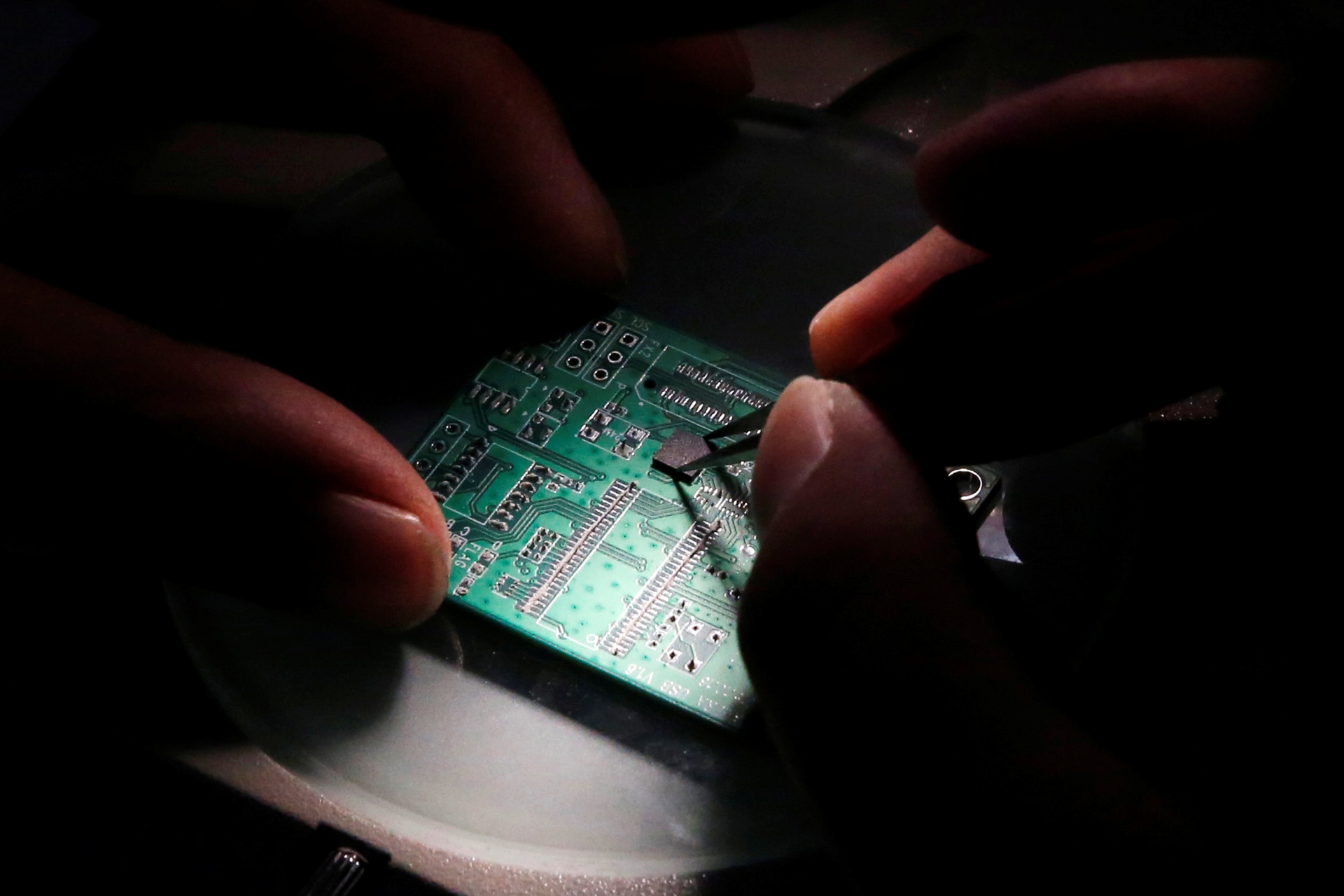

In the twenty-seven year history of CFIUS, a total of four deals have been blocked by presidents, including a Chinese-backed fund’s bid to purchase Lattice Superconductor, a U.S. chip-maker, earlier this year. These are not the only deals CFIUS has prevented from occurring, as many businesses withdraw their bids before they get to the president’s desk when it is unlikely that they will receive CFIUS approval. Even with these reviews, and the blocking of problematic transactions, Chinese investment in the United States reached forty-six billion dollars in 2016.

This year, a bipartisan group of senators introduced the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRMMA), which is meant to expand the jurisdiction of CFIUS and allow the committee to oversee a boarder range of transactions that could pose a threat to national security. The act appears to be motivated in part by an unreleased Pentagon report of the military applications of Chinese investments in the United States. Under the new legislation, CFIUS oversight would be expanded to include foreign investments near military facilities, minor-share investments in critical technology and infrastructure sectors, and transfers of dual-use technology to foreign entities. Acquisitions of critical technologies by “countries of special concern” would also be subject to CFIUS oversight. Though China isn’t mentioned by name, the bill’s authors haven’t been shy about discussing the legislation’s main target.

Some argue that expanded CFIUS oversight is contrary to the U.S. promotion of free trade. That may be true, but Washington constrains trade all the time, whether it is through economic sanctions, trade tariffs, or import quotas. Moreover, Chinese state-led capitalism makes it difficult to distinguish between private and state-owned businesses, and many private firms have strong ties to the Chinese government.

In addition, China has been historically disinclined to allow private foreign investment in many critical parts of the economy. Even though China recently relaxed some of its investment restrictions, it has traditionally maintained strict limits on foreign investment in its energy, transportation, and technology industries. Chinese firms, many with connections to the state, can invest billions in U.S. technology, but U.S. companies are often barred from doing the same.

China’s ambitions in high technology should be taken seriously. This past July, China released a plan to be the world leader in AI by 2030 and has pledged to spend billions of dollars to reach its goal. Private venture capital funds and state-owned entities are also expected to raise over one trillion dollars to invest in China’s domestic technology sector, which is ripe for innovation and flooded with talent. At the same time, the Trump administration is proposing budget cuts that slash government investment in U.S. scientific research, which could be devastating for U.S. innovation over the long-term.

While the proposed CFIUS reform might level the playing field by preventing China from acquiring critical technologies, it is only a small step in guaranteeing continued U.S. technological dominance. According to a report commissioned by the Obama administration, “the United States will only succeed in mitigating the dangers posed by Chinese industrial policy if it innovates faster.” To assure that, Washington would have to commit to spending more on technology-related research and development.