Most analysis of China’s economy emphasizes the risks posed by China’s high level of investment, and the associated rise in corporate debt.

Investment is an unusually large share of China’s economy. That high level of investment is sustained by a very rapid growth in credit, and an ever-growing stock of internal debt. Corporate borrowing in particular has increased relative to GDP. Not all this investment will generate a positive return, leaving legacy losses that someone will have to bear. Rapid credit growth has been a fairly reliable indicator of banking trouble. China is unlikely to be different.

More on:

Concern about the excesses from China’s investment boom permeate the IMF’s latest assessment of China, loom large in the BIS’s work, and the blogosphere. Gabriel Wildau of the Financial Times:

"Global watchdogs including the International Monetary Fund and the Bank for International Settlements (not to mention this blog) have become increasingly shrill in their warnings that China’s rising debt load poses global risks."

Yet I have to confess that defining China’s primary macroeconomic challenge entirely as "too much debt financing too much investment" makes me a bit uncomfortable.

Investment is a component of aggregate demand. Arguing that China invests too much comes close to implying that, as a result of its credit boom/ bubble, China is providing too much demand to its own economy, and, as a result, too much demand for the global economy.

That doesn’t seem entirely right.

More on:

China’s banks have not needed to borrow from the rest of the world to support the rapid growth of domestic credit. China’s enormous loan growth, counting the growth in shadow lending, has been self-financed; deposits and shadow deposits seem to exceed loans and shadow loans.*

Most countries in the midst of credit booms run sizable external deficits. China, by contrast, still runs a meaningful current account surplus. China is exporting savings even as it invests close to 45 percent of its GDP.

And even with an extraordinary high level of domestic investment, China’s economy still, on net, relies on demand from the rest of the world to operate at full capacity. That is what differentiates China from most countries that experience a credit and investment boom.

An alternative frame would start with the argument that China saves too much.

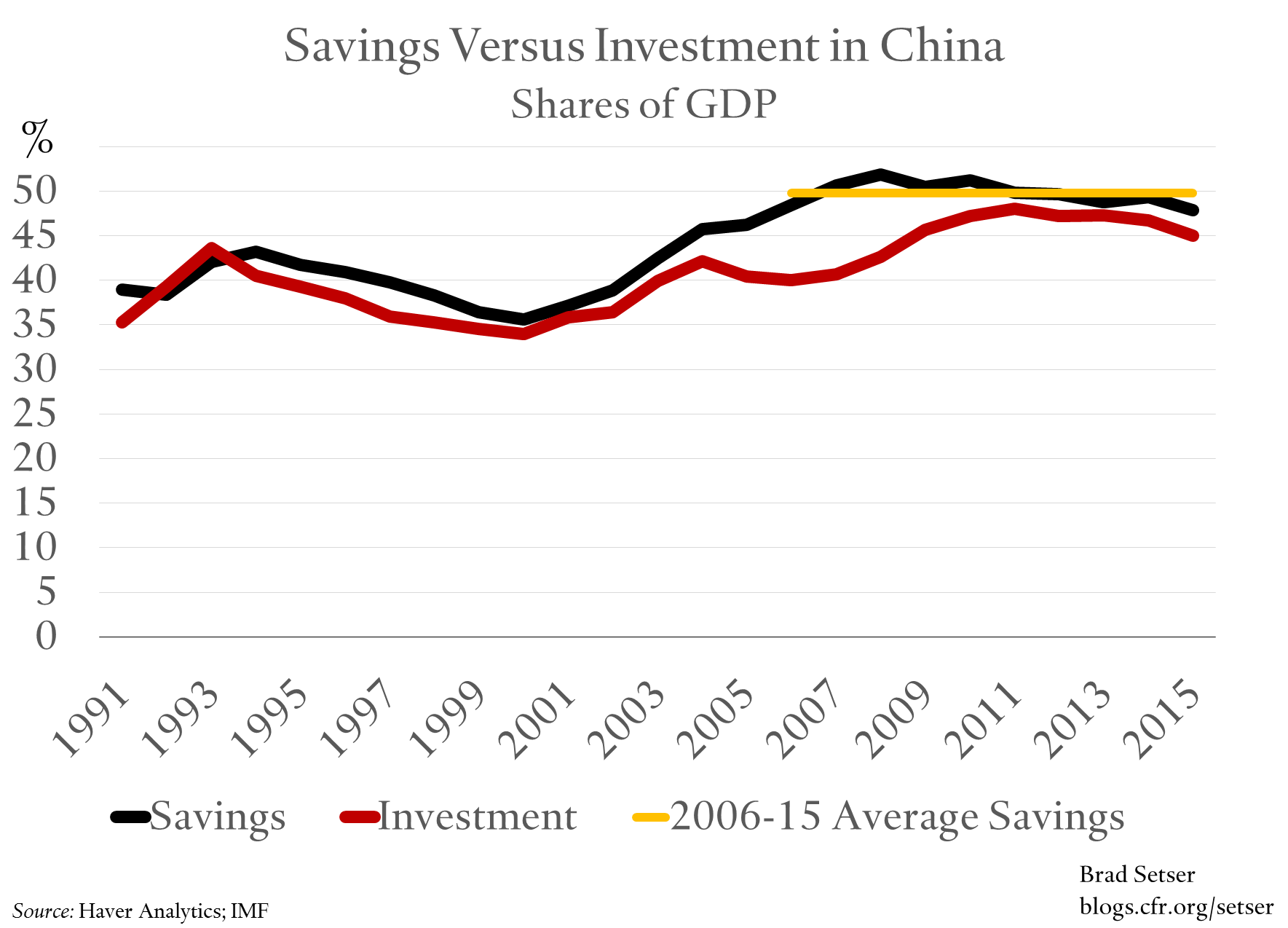

A high level of national savings—national savings has been close to 50 percent of GDP for the last ten years, and was 48 percent of GDP in 2015, according to the IMF (WEO data)—creates an on-going risk that China will either over-supply savings to its own economy, leading to domestic excesses, or to the world, adding to the risks from global payments imbalances.

From this point of view, the high level of investment, and the risks that come from high levels of investment, flow in part from the set of policies that have given rise to extraordinarily high levels of domestic savings.

After the global financial crisis, the vast bulk of Chinese savings now is invested, no doubt rather inefficiently, at home. Bai, Hsieh, and Song’s excellent Brookings Paper on Economic Activity emphasizes that the surge in investment after the crisis was very much a product of government policy.

But even with a high level of investment spurred by rapid growth in domestic credit some Chinese savings still bleeds out into the world economy. And China’s savings exports—exporting savings is an alternative way of describing a current account surplus—create difficulties when most advanced economies themselves are struggling with too much savings of their own, and have trouble putting all the savings now available in their economies to good use. That is what low global interest rates and weak global demand growth are telling us.

Thus, from the rest of the world’s point of view, a fall in investment in China on its own poses a set of risks.

Less investment means less demand for imports. The imported component of investment is, for now, much higher than the imported component of consumption. China’s recent import growth has been quite weak. It is increasingly clear that the slowdown in Chinese investment in 2014 and 2015 had a larger global impact—counting the second-order impact on commodity prices and investment in commodity production—than was initially expected.**

If less investment leads to a shortfall in growth in China and monetary easing, it would also tend to push China’s exchange rate down—resulting in the risk that China would both import less and export more. That isn’t good for a world short on demand and short on growth.

From the point of view of the rest of the world, the “win” stems from a fall in Chinese savings, not a fall in investment.

Lower savings would mean China could invest less at home without the need to export savings to the rest of the world.

Lower savings implies higher levels of consumption, whether private or public, and more domestic demand.

Lower savings would tend to put upward pressure on interest rates, and thus reduce demand for credit. Higher interest rates would tend to discourage capital outflows and support China’s exchange rate.

That’s all good for China and good for the world. It would result in lower domestic risks and lower external risks.

So I worry a bit when policy advice for China focuses primarily on reducing investment, without an equal emphasis on the policies to reduce Chinese savings.

To take one example, the IMF’s last Article IV focused heavily on the need to slow credit growth and reduce the amount of funding available for investment, and argued that China should not juice credit to meet an artificial growth target.

I agree with both pieces of the IMF’s advice. But I also am not sure that it is enough to just slow credit.

I would have liked to see a parallel emphasis on a set of policies that would help to lower China’s high national saving rate.

The IMF’s long-run forecast assumes that China’s demographics—and the policy changes already in train (a half point projected increase in public health spending, for example)—will be enough to bring down China’s savings (as a share of GDP) at a faster clip than Chinese investment falls (as a share of GDP); see paragraph 25 of this paper. Even as the off-balance sheet deficit falls and the on-budget fiscal deficit remains roughly constant.***

Mechanically, that is how the IMF can forecast a fall in the current account deficit alongside a fall in investment and a fall in China’s augmented fiscal deficit.

So the IMF’s external forecast in effect makes a big bet on the argument that Chinese savings is poised to fall significantly even without major new policy reforms in China. The actual fall in savings from 2011 to 2015 was rather modest, so the IMF is projecting a bit of a change.

The BIS also has long emphasized the risks from China’s rapid credit growth. Fair enough: the BIS has a mandate that focuses on financial stability, and there is no doubt that China’s very rapid pace of credit growth is adding to range of domestic financial fragilities.

To my knowledge, though, the BIS hasn’t warned that in a high savings economy, slower credit growth without parallel reforms to reduce the savings rate runs a substantial risk of leading to a rise in savings exports, and a return to large current account surpluses.

From 2005 to 2007, China held credit growth down through a host of policies—high reserve requirements and tight lending curbs on the formal banking system, and limited tolerance of shadow finance.

The result? Fewer domestic risks no doubt. But also a policy constellation that led to 10 percent of GDP current account surpluses in China.****

Those surpluses, and the offsetting current account deficits in places like the U.S. and Spain, weren’t healthy for the global economy.

Do not get me wrong. It would be far healthier for China if it didn’t need to rely so heavily on rapid credit growth to keep investment and demand up. China’s banks already have a ton of bad loans and many almost certainly need a substantial capital injection. More lending likely means more bad loans. The risks here are real.

But I also would be more comfortable if the global policy agenda put somewhat more focus on the risks from high Chinese savings—as in China’s case, high domestic savings are a root cause of a lot of the domestic excesses. I am not convinced that China’s national savings rate will head down on its own, without any policy help.

* See, among others, Tao Wang of UBS—who has pulled together the relevant data in her market research.

** Both the IMF and the ECB have argued that the fall in investment explains much of its recent weakness in Chinese import growth, and thus help explain the recent weakness in global trade. The IMF and ECB papers build on work first done by Bussiere, Callegari, Ghironi, Sestieri, and Yamano. Both Chapter 2 (on trade) and Chapter 4 (on spillovers from China) of the most recent WEO imply that the 2014-15 investment slowdown had larger than initially expected global spillover.

*** A technical point. A large government deficit usually lowers national savings. So from a savings and investment point of view, a traditional government deficit tends to impact the current account by lowering savings. But it seems like much of the augmented fiscal deficit—the IMF’s term for the borrowing of local government investment vehicles and the like that doesn’t show up in formal definitions of even the “general government” fiscal deficit—has shown up as a rise in investment. The IMF’s adjustment thus implies private investment (and private credit growth) has been overstated a bit, and public investment understated. So if Bai, Hsieh, and Song are right, a fall in the augmented part of the augmented fiscal deficit would show up as a fall in investment, not a fall in national savings. The line between the state and firms is especially blurry in China, as many firms are owned by the state—but expanding the perimeter of “fiscal policy” to include various local financing vehicles that could be viewed as state enterprises requires some offsetting adjustments.

**** The BIS "credit gap" (data here, and here) was negative when China’s current account surplus was at its peak; that isn’t an accident. China was suppressing lending growth through loan quotas and high bank reserve requirements at the time.