China’s COVID-19 Comeback Rides On the Strength of Chinese Households

In 2023, China’s economic recovery will depend on the ability of the government to stimulate domestic consumption and on the resilience of Chinese households.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Zongyuan Zoe LiuMaurice R. Greenberg Senior Fellow for China Studies

By Zongyuan Zoe LiuMaurice R. Greenberg Senior Fellow for China Studies

Earlier this month, China released its economic data for the year 2022, revealing that the nation’s GDP had grown by only 3 percent, falling short of the government’s 5.5 percent growth target. The underperformance was attributed largely to the government’s strict COVID policies, which led to lockdowns and halted economic activity in major cities during the spring and summer. These policies sparked widespread protests in November, as citizens expressed frustration with the economic harm and social disruption caused by these policies. In response, the government changed course and by the end of December had relaxed several restrictions on movement, such as the requirement to show a negative virus test or scan a green health code before traveling to a different city. For many Chinese households, 2022 was a challenging year that tested their resilience and left them in a bit of an economic hole. Just how quickly Chinese households can climb out from that hole is critical to whether China’s economy can rebound and hit the current forecast of 5.1 percent growth in 2023, a key assumption to higher growth forecasts in the rest of the global economy. Using the latest data, we visualize the economic situation of Chinese households. In four charts, we describe the challenges to China’s economic recovery from COVID-19 presented by Chinese households.

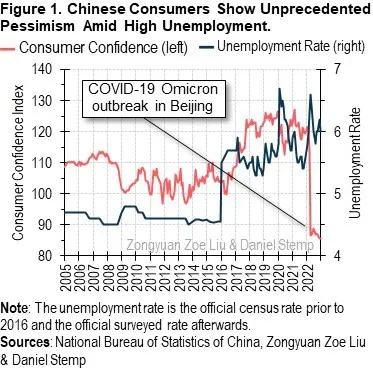

When considering the economic security of Chinese households, it is important to note that for 43 percent of the population that is thirty-five years old or younger (roughly six hundred million people), the past year represents the most trying period of economic stress and instability they have ever personally encountered. Figure 1 illustrates how, in the context of these peoples’ memory, both the unemployment rate and the consumer confidence index are historically bad. In December the unemployment rate stood at 5.5 percent, down from 6.1 percent in April but still well above the historical average. The youth unemployment rate (workers aged sixteen to twenty-four) was 16.6 percent in December, down from its July peak but still above the 2021 average of 14.2 percent. While the easing of COVID-19 restrictions will help to bring that number down further, it may take a couple of months before we see substantial positive effects. In early January, many migrant workers returned to their rural homes for the Spring Festival, and they may be slow to return to the cities without clear prospects for employment.

Even if the unemployment rate returns to pre-pandemic levels, it is uncertain whether Chinese households’ confidence in the economy will ever return to the same unbridled optimism that characterized the prior two decades. During April 2022, the Chinese Consumer Confidence Index slipped below one hundred for the first time, the threshold that indicates a generally negative outlook on the economy. In November, the index reached a new all-time low of 85.5. The December reading of the index will likely improve as it will capture some of the public’s sense of relief from the end of general lockdowns. However, it is important to note that confidence in the economy is not easily regained after an economic trauma. It took nearly five years for the US Consumer Confidence Index to recover from the effects of the 2008 Financial Crisis, and Chinese consumers may experience a similar hangover effect for several years.

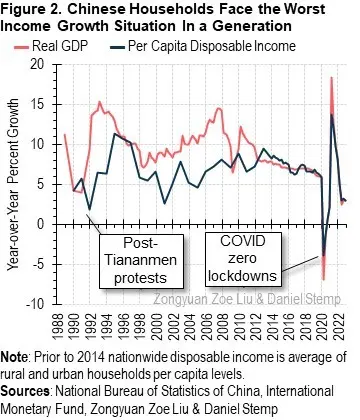

In several ways the year 2022 bookends a period of economic and political stability in China matched at its start by the year 1989. In both years, the Chinese public expressed their frustration with government policies through spontaneous nationwide protests. Figure 2 shows that during the last year, China’s economy and household incomes experienced historically slow growth. Per capita disposable income, the spending power of Chinese households, increased by just 2.9 percent year-over-year in Q4 2020. This is the slowest pace of growth since 1991 when China’s economy was dealing with negative export growth as fallout from the West’s reaction to the Chinese government’s handling of the 1989 mass protests. Back then the government was able to get China’s growth back on track by focusing on exports, culminating in China joining the World Trade Organization at the end of 2001. That same old playbook won’t work this time around. China is already the world leader in exports with a 12.3 percent global market share in 2022 compared to the next highest 9.7 percent for the United States. In many trade categories, the global export market is already saturated with Chinese products.

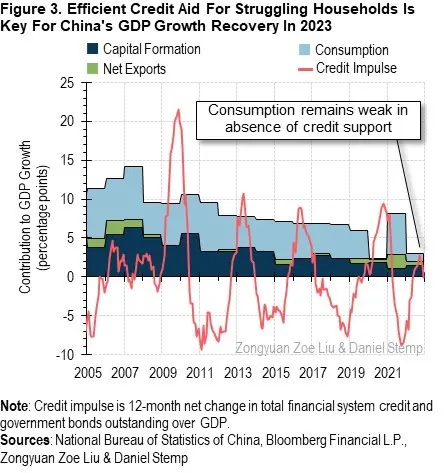

For China’s economy to rebound in 2023, the government needs to stimulate domestic consumption. Figure 3 shows that China’s growth faltered last year because domestic consumption collapsed when large segments of the urban population were placed under prolonged lockdown. Now that China has fully re-emerged from the lockdowns, the latest economic forecasts call for pent-up demand from China’s households to push retail sales growth higher to 7.3 percent year-over-year in 2023 (compared to only 1.4 percent in 2022) as the primary driver of overall GDP growth. However, to realize such a surge in consumption, Chinese consumers will need help with financing. The tightening of credit conditions in China over the last twelve months casts some doubt over whether consumer credit can expand enough to support the rapid expansion in consumption that forecasters have assumed for 2023. This presents a structural challenge to the Chinese banking system because it was designed to funnel credit to large enterprises, not to make consumer loans. Last year, Chinese banks were flush with cash but struggled to make loans in part because most banks’ business models are narrowly focused on corporate lending rather than building lifetime lending relationships with individual consumers.

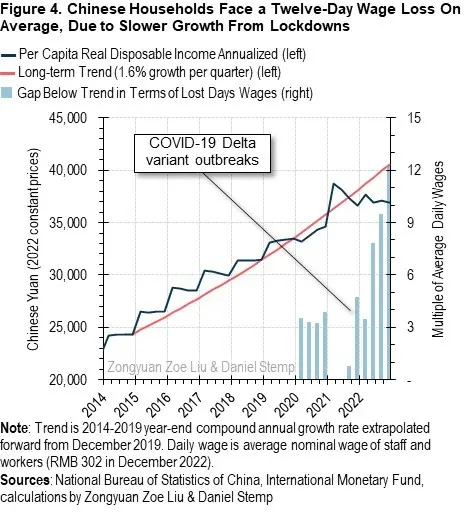

For the last thirty years, China’s households haven’t required much credit support from the banking system because fast income growth and high personal savings rates meant that Chinese consumers were mostly able to finance their own steady increase in spending. However, that may no longer be the case, as some Chinese households have likely adjusted their budgets to reflect lower income growth potential going forward. Figure 4 shows an estimate of the potential economic scarring suffered by Chinese households as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns. We estimate that the spending power of the average Chinese household is lower by the equivalent of about twelve days’ wages as compared to what it would have been if the pandemic had never occurred. This is a significant amount of missing income for Chinese households. According to a 2021 report by CCTV, about 40 percent of single people in China’s first-tier cities live mostly paycheck to check. While this decrease in spending power may be temporary, as faster growth in 2023 may repair much of the economic damage, it’s important to closely monitor economic data for signs of recovery or a lasting shift in consumer psychology.