Dubious Claims of Common Cause Between Bolton and African Critics of ICC

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Michelle GavinRalph Bunche Senior Fellow for Africa Policy Studies

By Michelle GavinRalph Bunche Senior Fellow for Africa Policy Studies

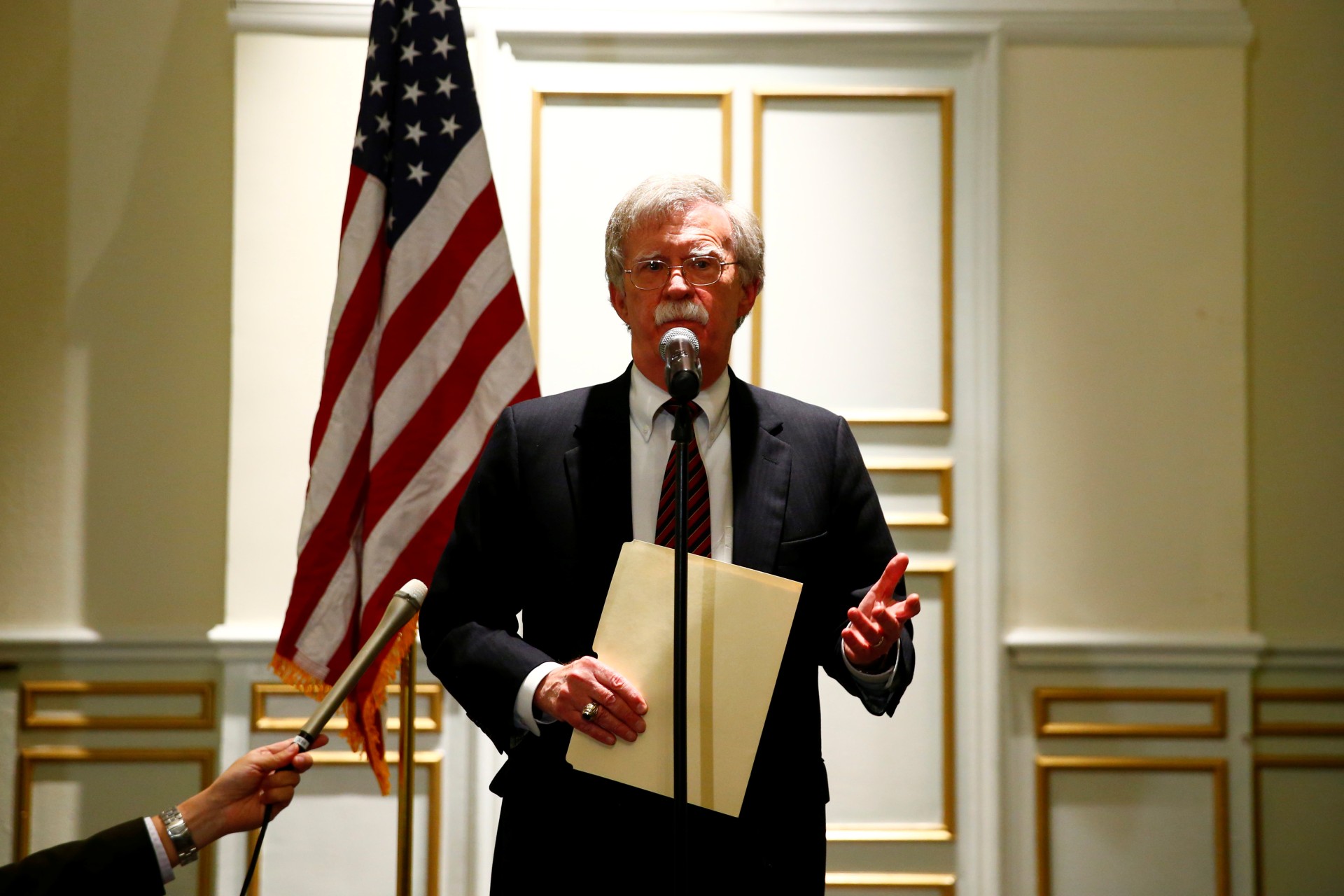

Earlier this week, President Trump’s National Security Advisor John Bolton delivered a blistering attack on the International Criminal Court, or ICC, long a scourge of his and his audience at the Federalist Society. In doing so, he joined many African leaders who have likewise condemned the ICC; in 2017 the African Union passed a nonbinding resolution calling for its members states to withdraw from the court. Indeed, Bolton noted the African opposition in his remarks, saying that “to them [African opponents] the ICC is just the latest European neocolonial enterprise to infringe upon their sovereign rights.”

That is certainly the way many African objections have been framed in the course of pointing out that atrocities occur around the world but the Court’s work has been almost entirely focused on Africa. Ironically, Bolton’s latest attack on the ICC was precipitated by the court doing the very thing that many Africans have been demanding—exploring abuses committed by great powers beyond the African continent.

But there is another and at least equally potent point of contention responsible for the rift between many African governments and the ICC—the issue of immunity for sitting heads of state, which is also an issue of interest to the White House. African governments’ discomfort with the ICC grew when the court issued an arrest warrant for Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir in 2009, creating a dilemma for host states whenever Bashir traveled on the continent. The discomfort spiked again when the court indicted President Uhuru Kenyatta and Vice President William Ruto of Kenya in 2011 (the charges against both Kenyan leaders were later dropped for insufficient evidence). It is not hard to imagine that President Pierre Nkurunziza of Burundi had these cases in mind when he reacted to a UN Commission of Inquiry Report accusing his government of grave human rights abuses by withdrawing Burundi from the Rome Statute.

The Court was designed in part to provide for accountability in places where the desire for justice was strong but domestic judicial institutions were weak—an apt description of many African states. They make up the largest block of signatories to the Rome Statute that established the Court, and in many cases African states have referred crimes committed within their own borders to the ICC for prosecution. Interestingly, at the height of the tension over the Kenyan indictments in 2015, Afrobarometer found that over 60 percent of Kenyans believed the cases were important for fighting impunity in their country. It’s true that Africans chafe at the ICC’s almost singular focus on their region. But it is equally true that the agenda of African leaders who have been most vocal in opposing the ICC is not necessarily aligned with the desire of many Africans for fairness and accountability—even for the most powerful. Bolton’s attempt to buttress his diatribe with African perspectives seems oblivious to this desire.