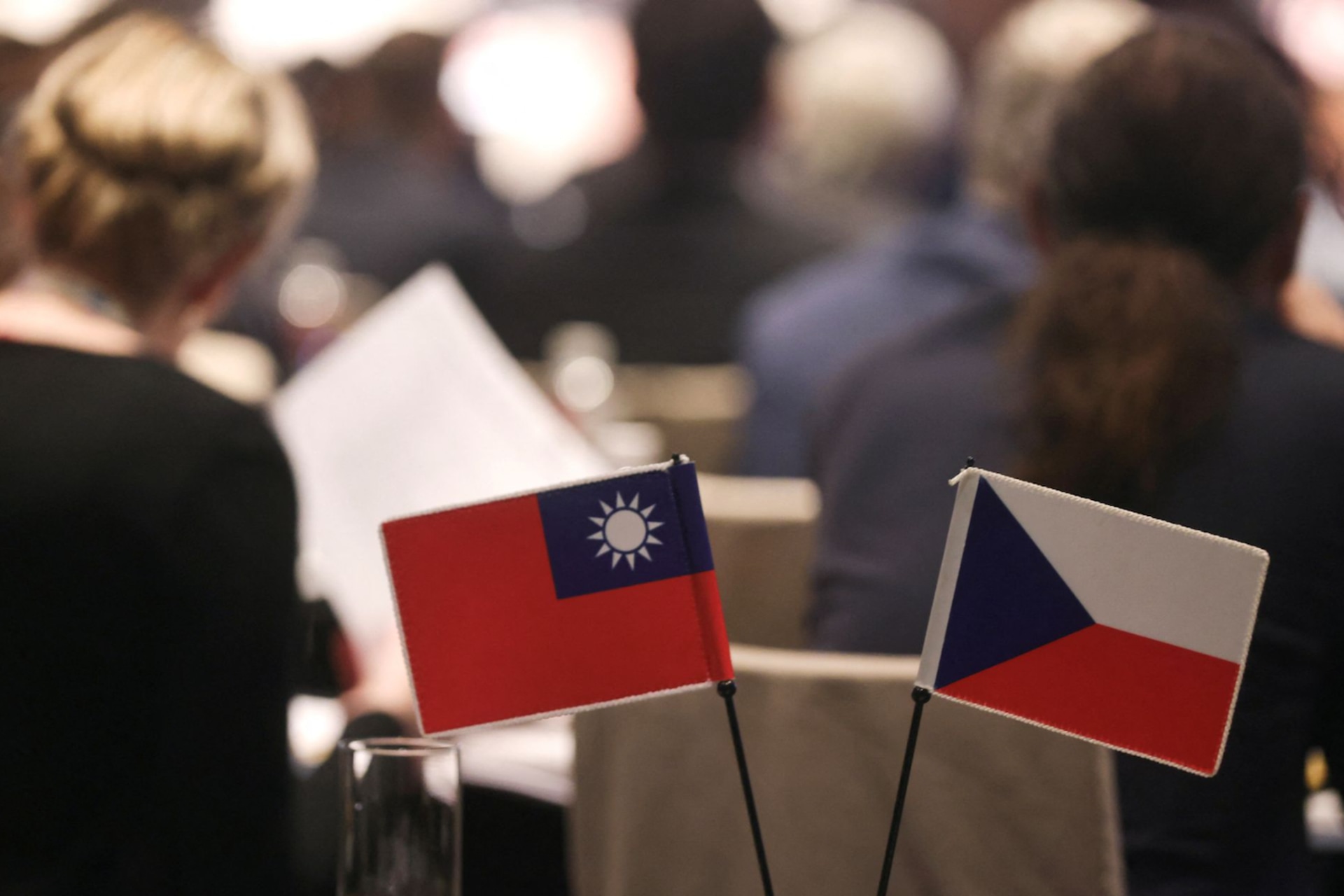

How the Czech Republic Became One of Taiwan’s Closest European Partners and What It Means for EU-China Relations

Since 2018, China-Czech relations have deteriorated as Prague pursues closer relations with Taipei, jeopardizing status quo EU-China relations.

By experts and staff

- Published

On March 25, the Czech Speaker of the Lower House led a 150-member delegation to Taiwan, resulting in eleven Memoranda of Understanding promising to enhance bilateral economic, political and cultural ties. In a further affront to Beijing, Taipei and Prague negotiated terms of an arms deal in which Taiwan would acquire the latest generation of Czech self-propelled howitzers in addition to large missile transport trucks. The two also agreed to further develop ties between their respective leading national security think-tanks and collaborate on drone research. While this was not the first high-level Czech visit to Taiwan, it entered qualitatively new territory by pursuing military cooperation. Moreover, this visit was the first since China sanctioned fellow European Union (EU) member Lithuania in 2021 for allowing the opening of a “Taiwanese Representative Office” in Vilnius. This shows the resolve of the Czech delegation and their willingness to strengthen ties with Taiwan in spite of potential economic retaliation.

After high-profile visits from the Lower and Upper House Speakers, all eyes turn to newly elected President Petr Pavel, who has promised to visit Taiwan despite threats from Beijing. With the recent election of the former NATO General, the President of the Czech Republic has gone from being one of the most China-friendly heads of state in the EU to possibly the most hawkish. In early January 2023, Chinese President Xi Jinping attempted to bridge the gap between the outgoing and incoming administrations by inviting outgoing Czech President Miloš Zeman to a video conference aimed at “deepening and broadening bilateral cooperation.” However, weeks later, President-elect Pavel accepted a phone call from Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen, becoming the first EU head of state to directly communicate with a Taiwanese President. Further upending diplomatic norms, Pavel verbally committed to visiting Taiwan, which would make him the first EU president or prime minister to ever do so. Unsurprisingly, this drew the ire of Chinese officials and led to several threatening statements from the Chinese Foreign Ministry. While it is unclear what Beijing’s material response would be if the visit occurs, it is abundantly clear that Sino-Czech relations are on a downward trajectory and the potential fallout will have EU-wide consequences.

While the election of President Pavel symbolizes a drastic foreign policy shift in the Czech Republic, Prague had already begun a gradual move from Beijing before the change in government. Despite former President Zeman’s amenability to China, Sino-Czech relations have been souring since at least 2018 when the Czech National Cyber Agency issued an alert warning of the national security risks posed by China’s Huawei and ZTE. The alert threatened Huawei’s $8 billion 5G network expansion approved by President Zeman, and it jeopardized Huawei’s growth in Europe more broadly. In the same year as the Huawei alert, political outsider Zdeněk Hřib became mayor of Prague, replacing his China-friendly predecessor who had facilitated the Prague-Beijing sister city agreement in 2016. Mayor Hřib immediately angered Chinese officials by cultivating close ties with Taiwan, where he had studied abroad during his medical training.

Prague Draws Closer to Taipei

China’s aggressive responses – ranging from threats of litigation in the 2019 Huawei case to threats of sanctions in response to a proposed 2020 diplomatic visit to Taiwan – have led Prague to develop even closer relations with Taipei. So far, the material implications of the Sino-Czech diplomatic fallout have been limited to cultural exchange. Taiwan has capitalized on the rift between the two states and has largely replaced Chinese cultural institutions in the Czech Republic. Just three months after Prague canceled its sister city agreement with Beijing, the Czech capital signed a new sister city agreement with Taipei. After China canceled the Prague Philharmonic tour of Beijing in 2019, the orchestra performed in Taiwan on its national day in 2022 instead. After the 2019 dismantling of the Charles University Czech Chinese Center, Taiwan opened a “Taiwan Center for Mandarin” in Prague offering the same sorts of cultural events and language courses as would a Confucius Institute. Mayor Hřib even found an alternative to the giant panda that China refused to send to the Prague Zoo: the Pangolin – a scaly anteater saved from extinction through Taiwanese conservation efforts.

Member of European Parliament Jiří Pospíšil summed up Prague’s embrace of Taiwan succinctly: “Taiwan is a several times larger investor in the Czech Republic than the People’s Republic of China, and on top of that it also respects the principles of freedom and democracy.” The reality is that Chinese investment promises never came to fruition. The “16+1 format” meant to unify business regulations and become an investment vehicle into Central and Eastern Europe was underwhelming for all parties involved. Even former President Zeman conceded that Chinese investment promises were not entirely kept. Investments that did materialize included prestige acquisitions of Prague Football Club Slavia and brewery Lobkowicz, which seemed more politically than economically motivated. By contrast, Taiwan’s flagship investment, electronics manufacturer Foxconn CZ, created 5,000 jobs and has grown to become the sixth-largest company in the Czech Republic by revenue.

In addition to the unkept trade promises, in the eyes of many Czechs, China has become inextricably linked to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Czech Republic is a frontline state to the war – housing the most Ukrainian refugees per capita in the EU – and many view China as an enabler of Russian aggression. While former President Zeman may have privileged trade above all other concerns, President Pavel’s campaign was built on a “values-based approach to politics” in the spirit of the Czech Republic’s first post-communist president, Václav Havel. Havel cultivated close ties with the Dalai Lama and Taiwanese leaders. Moreover, like many Czechs, Havel felt a close affinity for Taiwan, having lived in a satellite state at the mercy of a powerful authoritarian neighbor.

The Potential for Retaliatory Sanctions against the Czech Republic

When President Havel took office in 1993, China was a distant force with a GDP no larger than Canada’s. Thirty years later, President Pavel finds himself in a new geoeconomic reality where China holds considerable sway over certain EU members and threatens EU trade cohesion. The case of Chinese sanctions against Lithuania in 2021 can serve as both a predictor of Chinese willingness to use sanctions against the Czech Republic and a litmus test for EU Cohesion.

Lithuania faced export, import bans, and investment bans in retaliation for hosting a representative office from “Taiwan” rather than “Chinese Taipei.” When sanctions appeared to have little effect, China ratcheted up the pressure by imposing secondary sanctions which barred Lithuanian-origin goods traded by other countries from entering China. The EU immediately filed a complaint to the WTO and will provide a relief fund for Lithuanian companies damaged by the ban. Germany’s reaction was unlike the rest of the EU. Despite some German officials‘ public statements of solidarity with Lithuania, Lithuanian officials say they face pressure from German businesses and the German-Baltic Chamber of Commerce to concede to Chinese demands.

The Czech Republic, like Lithuania, is relatively insulated from potential Chinese sanctions due to minimal Czech investment and trade ties with China. In 2021, China made up a fraction of the 6% of inward Czech FDI flows from non-European countries. In the same year, the Czech Republic exported around 1% of its goods and services to China. A trade and investment ban would inflict limited damage to the Czech economy and would likely only be used by China as a political signaling tool. However, if China pursued a strategy of informal secondary sanctions – pressuring German automakers and electronics companies to eliminate Czech-origin goods – this would prove devastating to Czech industry, which ships nearly a third of its exports to Germany. Germany’s lukewarm commitment to EU solidarity in the face of Chinese coercion is concerning, but what should comfort Prague is that economic dependence goes both ways: complying with Chinese economic coercion against Prague would be painful for Germany, as Czech auto parts, machinery, and electronics manufacturing form an integral part of Germany’s export machine. The same German industries that depend on Czech supply lines have been major advocates of a dovish China policy. If China were to introduce secondary sanctions on the Czech Republic, Germany could be forced to reconcile its China position with the rest of the EU.

China’s reliance on economic coercion to achieve political goals has largely been ineffective. Implementing a sanctions regime on the Czech Republic risks uniting Europe and forcing Germany to abandon its economics-first China policy. On the other hand, if China merely offers another strongly worded response to President Pavel’s planned Taiwan visit, then Beijing could fail to deter other EU states from doing the same in the future. Beijing also knows that major European economic powers such as Germany, France, the Netherlands, Spain, and Italy are heavily reliant on trade with China—unlike the Czech Republic and Lithuania—and are thus less likely to risk their bilateral economic relationships. The countries most likely to follow the Czech Republic and Lithuania’s lead are small EU-member states in Central and Southern Europe that have the most limited bilateral economic ties with China. If this trend continues, China will have to determine whether it is willing to impose costs on minor European states for seeking closer ties with Taiwan at the risk of damaging its economic relations with its major European trading partners.

Daniel McVicar is a Research Director for the White House Writers Group (WHWG).