How Morrison Won – and What His Win Means for the U.S.-Australia Alliance

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Guest Blogger for Asia Unbound

James Curran is a professor of modern history at Sydney University.

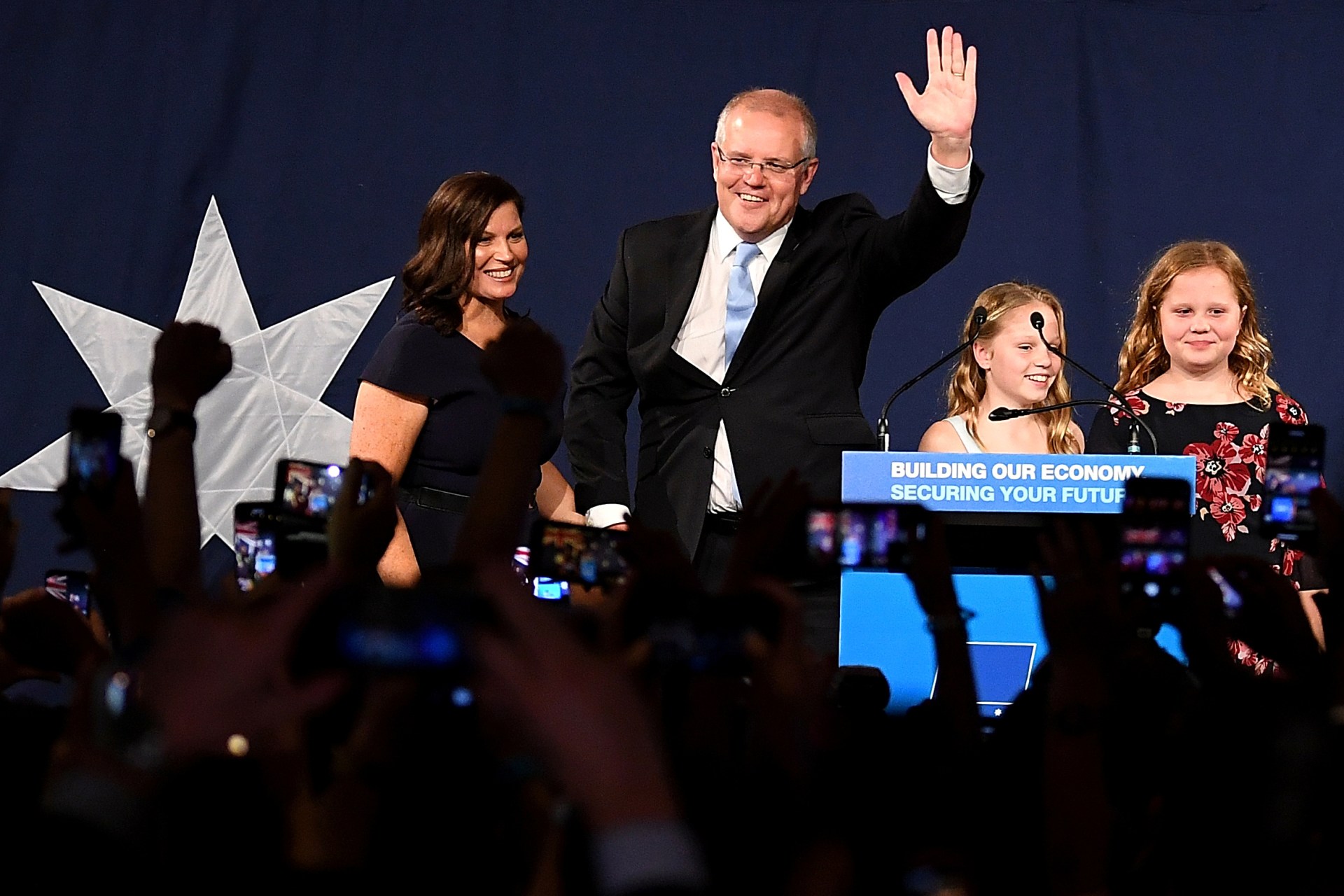

As the dust begins to settle on the stunning, unexpected result from the Australian elections over the weekend, the re-elected Prime Minister Scott Morrison will face once more the challenge of a turbulent strategic environment.

Central to that task will be how he manages the relationship with a White House that is increasingly ratcheting up the pressure on Beijing across both the economic and security fronts.

Morrison’s win owes much to the ruthlessly clinical scare campaign he ran against Labor leader Bill Shorten’s ambitious agenda for domestic reform, especially his contentious plans for the nation’s taxation system. The result means the prime minister has pulled off a miracle win that virtually no poll or pundit predicted even a few months ago, when the ruling Liberal-National Coalition was reeling from the combination of its decision to dump Malcolm Turnbull as leader and an ascendant Labor party seemingly cruising to electoral triumph. With the changes to party rules now making it much more difficult to remove sitting prime ministers, Morrison’s power within the Coalition appears likely to be impregnable. U.S. observers can be sure that there will be no more revolving doors of Australian prime ministers.

During the election the parties’ respective positions on foreign policy were barely audible amidst the din of debate over tax policy and climate change. Such a state of affairs is not unusual for Australia: in the past 60 years only one election has been fought over foreign policy: that of 1966 in the midst of the Vietnam War.

Nevertheless, a troubled world awaits. Since the 1970s, when both sides of Australian politics began in earnest the policy of comprehensive engagement with Asia, Canberra has been able to conduct its regional diplomacy largely in the knowledge that economic growth and prosperity did not necessarily have to come at the expense of strategic stability. The assumption that U.S. failure in Vietnam would precipitate a U.S. withdrawal from Asia proved a mirage, and when China’s economic rise began to accelerate in the 1990s, Washington retained military predominance in the region.

The disruptive elements to this picture have been clear for some time: a United States that, while still active in the region, can no longer call all the strategic shots and is looking for its allies to do more, and a China steadily and intentionally making clearer its goal of achieving regional strategic predominance. Other powers too, especially India and Indonesia, are rising rapidly at the same time, with demographics on their side.

Accordingly, the practice of Australian diplomacy has been getting harder. The one constant for Scott Morrison is that, issue by issue, it will get harder still.

But according to early press reports there appears to be a palpable sense of relief in Washington that the Morrison government has been returned. Senior U.S. officials have told one Australian scribe that the election result is a bonus for the relationship: ‘We know what we are dealing with’, one said, ‘and we like it’.

For his part President Trump tweeted an image of Morrison replete with a series of thumbs-up emoji and a sausage sandwich drenched in ketchup. On one interpretation, such imagery and words are the currency – even if in this case somewhat tawdry – of an alliance built around shared values and enduring bonhomie. A less generous interpretation would be that both Trump’s twittering and the officials’ comments show that the United States retains its longstanding tendency to take Australia somewhat for granted.

Washington insiders will need to be careful, however, in jumping to quick or easy conclusions about just how Morrison will react to a U.S. China policy trending increasingly towards containment. This is a disturbing development for Australian leaders and policymakers. One of the nation’s most eminent strategic thinkers, the former head of foreign affairs Peter Varghese, has commented that in the event that trajectory in American policy continues, it would be “very uncomfortable for Australia…we could find ourselves confronting that possibility of having to say no to the U.S. on a matter that it considers to be a core national security interest”.

On just which issues Australia would find itself compelled to say ‘no’ to Washington where China is concerned are, of course, not yet clear. But Morrison is unlikely to reverse the policy of both the Abbott and Turnbull governments on conducting freedom of navigation operations within the 12-nautical mile zone of contested territories in the South China Sea. Similarly, his government will continue to eschew the rhetorical armoury that comes with the kind of Cold War thinking articulated by Vice-President Pence in his speech on China to the Hudson Institute in October 2018.

In Morrison’s first major address on foreign affairs in November last year, he repeated the call of his predecessors for the “peaceful evolution of our own region”, underlining the importance of U.S.-China relations not becoming “defined by confrontation”. Then, announcing what some dubbed a “Pacific pivot” – aimed at increasing Australian funding to its near neighbors in an attempt to rebut China’s growing influence there – Morrison nevertheless rejected any notion that it should carry a new ‘Cold War’ branding.

The first two years of the Trump administration has seen Australia play a strong sentimental card in the bilateral relationship – witness the Australian incantation of “mateship” and military sacrifice as a means of catching the U.S. president’s attention. Morrison will have no trouble in giving renewed voice to those alliance shibboleths.

But increasingly Australia, like other U.S. allies in the region, will need to play a different card in managing the alliance with Washington: namely that of the responsible ally that is not afraid to tell its great power protector what it might not necessarily want to hear. And here the task is to advise the United States on the folly of going down the containment path in dealing with China. It is all very well for Australian governments to utter the soothing words about wanting to see a region still characterised by U.S. leadership. But it needs to make the case to Washington that the key to its ongoing strategic relevance in Asia lies not in recycling cold war dogma, but in Washington improving its own performance in the region. That’s going to be a tough argument to sell to an U.S. president repeatedly asking allies themselves to step up.