Imports Normally Would Have Subtracted More From 2016 U.S. Growth

More on:

I follow the news, some would say obsessively. I know there are far more important things afoot than backward looking analysis of the United States’ 2016 economic performance.

But I do think in some ways the U.S. was lucky not to have slowed more in 2016.

Why? Because import growth stalled, and imports did not subtract as much from U.S. growth as normally would be expected (and yes, that obviously wasn’t the dominant narrative of the 2016 election).

Plus the U.S. essentially got a small GDP boost as a result of a bad harvest in Brazil that raised U.S. soybeans exports in q3 (a rise that was only partially reversed in q4). The U.S. isn’t (yet) a commodity-driven economy, but it also isn’t (yet) a robot-based intellectual property rights (IPR) royalty-driven economy totally divorced from natural sources of economic volatility.

Imports are essentially a function of domestic demand growth and the exchange rate. More domestic demand than the exchange rate: the exchange rate in nearly all careful studies tends to have a stronger impact on U.S. exports than on U.S. imports. In the Fed’s U.S. international transactions model, for example: "The equations for goods and services exports predict that a 10 percent appreciation of the real dollar would reduce the level of overall real exports by about 7 percent after three years. After three years, the model predicts that real imports would be almost 4 percent higher."

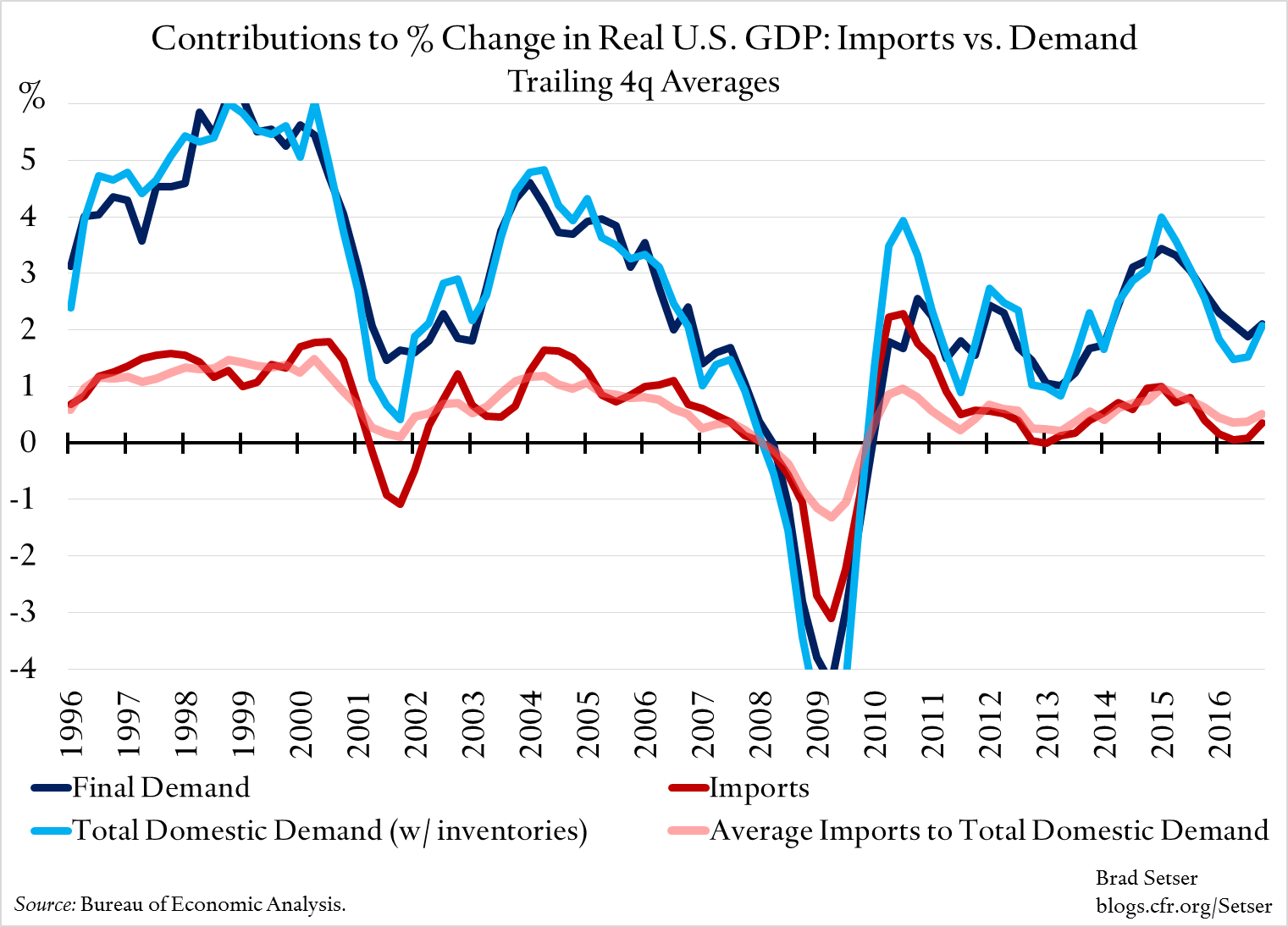

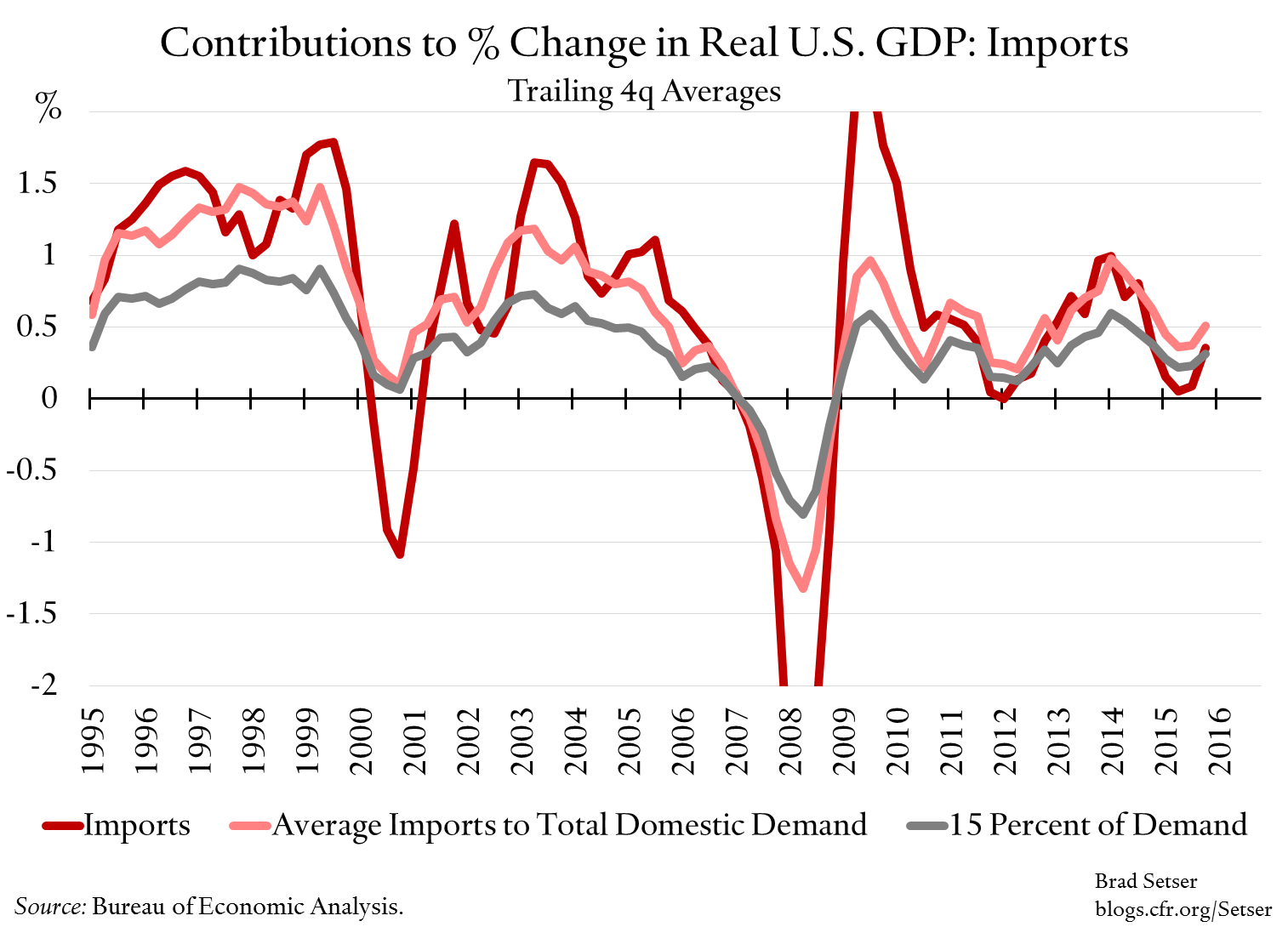

Over the last twenty years the negative contribution of imports to growth—think of it as U.S. demand that is shared with the world—has been about 25 percent of U.S. domestic demand growth. So typically 75 percent of any increase in U.S. demand goes toward domestic output, and 25 percent goes to the rest of the world (the U.S. of course also benefits from demand growth elsewhere, as growth outside the U.S. pulls up exports).

That is somewhat higher than that import share of GDP—as one would expect, if, over time, the import share of GDP is rising.

But something strange happened in 2016. From mid-2015 to mid-2016 (I like to look at the change over four quarters, a typical year-over-year comparison is the average over the last four quarters versus the average over the preceding four quarters so it uses eight quarters of data rather than four) U.S. imports were essentially flat (the negative contribution over four quarters was only 5-10 basis points of GDP) while U.S. demand growth—even counting inventories—contributed 1.5 to 2 percentage points to GDP growth.

Based on normal historical relationships, the expected drag from imports at various points over the last year should have been 35 to 50 basis points of GDP (using the trailing 4q average of contributions as the measure). Even if you believe the elasticity of imports to growth has now fallen and it should track the share of imports in the economy, imports should have increased by about 15 percent of demand growth, so the drag from imports mechanically should have been 20 to 30 basis points of GDP.

And generally speaking, the dollar’s strength over this period should have led imports to over-perform domestic demand in a standard model. That obviously did not happen.

No wonder the Fed’s trade model was puzzled. The recent Federal Reserve staff paper notes "for the given values in domestic demand and relative prices (with appropriate lags), the [Fed] model predicts year-over-year import growth well above actual import growth for every quarter since the second of quarter 2015.

The rise in imports in q4 brought the q4-2016/q4-2015 number in line with historical norms, but not above it. The dollar’s impact still isn’t obviously in the data.

There are explanations for the weakness of imports of course. The latest modelling techniques for imports disaggregate domestic demand growth into its components, as import growth is linked more closely to investment growth than consumption growth. Modeling the components individually allows the Fed staff to get a much better fit. I would though note that over the 2015/2016 U.S. import slowdown consumer goods imports were generally weak, not just capital goods imports.

So the odds are that—absent a big shift in trade policy (and well the odds now favor a big shift in trade policy)—imports will subtract a bit more from growth going forward. And exports—which tend to respond to the exchange rate—are likely to remain weak (and odds are that they will get weaker thanks to the global response to the expected change in U.S. trade policy).

One more point about the past, one I missed in real time. U.S. domestic demand growth accelerated in the course of 2014. Why does this matter? The standard forecast for 2015 was that the fall in oil prices would strengthen U.S. growth by supporting household real income, and thus demand growth. That implied a further acceleration from the relatively strong base of 2014, which would have required that the contribution from domestic demand to growth rise above three percentage points. That obviously did not happen. With hindsight, the risk always that the relatively strong pace of 2014 demand growth would not be sustained was underestimated, particularly given the drag from falling commodity prices on investment.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store