It is hard to put lipstick on a pig (or even an ox)

More on:

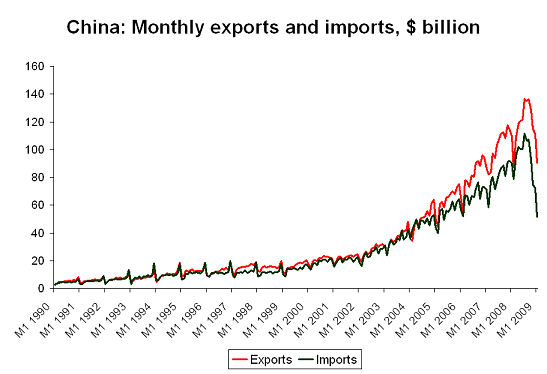

The sharp fall in China’s exports (down 17.5% y/y) and imports (down 43% y/y) shouldn’t have been a complete surprise. Korean and Taiwanese exports are down far more than China’s exports, in large part because of sharp falls in their exports to China. And, given the intra-Asian supply chain, that has long augered bad news for China.

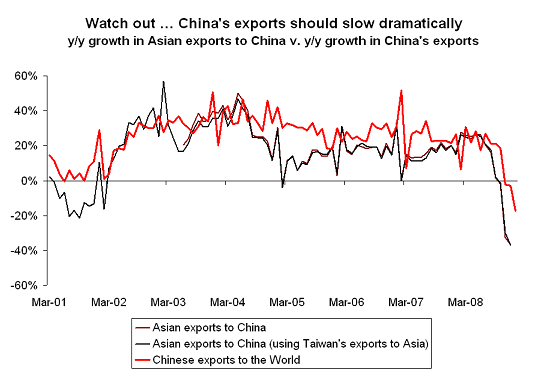

The Chinese New Year cut into China’s January exports and imports. After adjusting for this, China’s exports are down, but not quite as much as the headline figure suggests. But that, alas, likely implies further falls in the future. Even if -- as Stephen Green highlights in his latest note -- "processing" exports (i.e. exports with significant imported content) are falling far faster than non-processing exports, it is a little hard for me to see how Korean and Taiwanese exports to China could be down 40% if Chinese exports are only going to fall 5-10%.

Historically, the correlations between Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese exports to China and China’s exports to the world have been fairly tight. Of course, China’s exports now have more domestic content, so the correlation could change. But I am worried. Paul Swartz helped with the following chart:

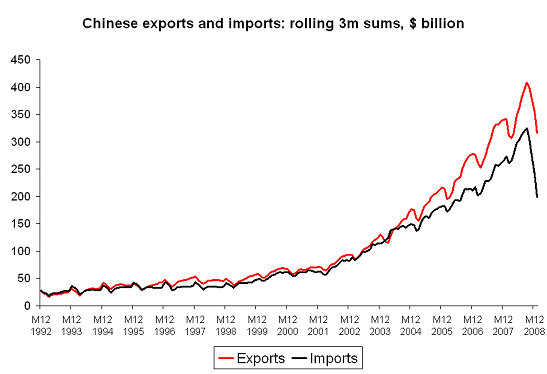

The current downdraft is clearly far more than just an artifact of the seasonality in China’s trade. A rolling 3m sum of China’s exports and imports smooths out some of the volatility. Exports and imports usually do fall in the first quarter -- but nothing like they are falling now. The trough -- on a rolling 3m basis -- usually comes in March, not January. Yet we already know the this year’s trough will be a lot lower than last year’s trough.

What worries me the most? The possibility that the sharp y/y fall in imports doesn’t just reflect a fall in imported components or a fall in commodity prices, but rather a major deceleration in China’s domestic economy.

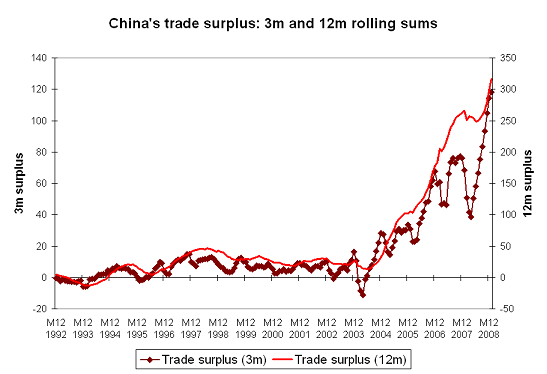

In some sense, it is hard to imagine a worse combination. China’s export are falling, making China understandably reluctant to allow its currency to appreciate. But China’s trade surplus is also rising ... certainly in nominal terms and quite possibly in real terms. That isn’t good for the world.

At a time when the world is short demand, China seems to be subtracting from global demand not adding to it. The best solution: an absolutely enormous domestic stimulus in China.

One last note: the PBoC’s other foreign assets were unchanged in December. That implies that China’s reserve growth -- counting its hidden reserves -- was somewhat larger than I initially estimated and that hot money outflows were somewhat smaller. The basic story though remains unchanged -- for the first time in a long time, reserve growth lagged the trade surplus, implying significant capital outflows.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store