Korea, the “Germany” of Northeast Asia…

Korea has no shortage of fiscal space. It should use it.

Korea, like Germany, is an export driven economy that has been hit hard by the recent slowdown in global trade. Output fell in the first quarter.

Like Germany, Korea specializes in manufacturing. It has been slowed by the broader global slowdown in auto demand—and Hyundai isn’t doing quite as well in North America as it once did. Korea has also seen its terms of trade deteriorate thanks to the recent fall in the price of many semiconductors.

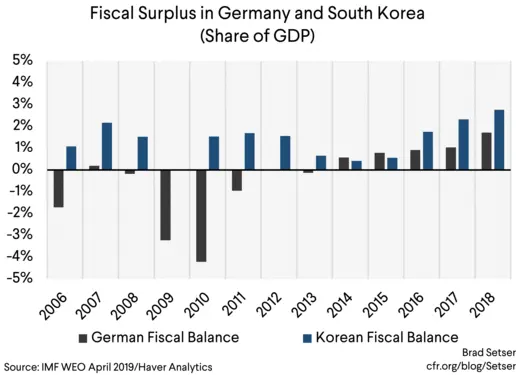

And Korea, like Germany, has been reluctant to use its obvious fiscal space even with a slowing economy. Gross government debt is just under 41 percent of GDP, and on a net basis, the government is a creditor (it has more assets than liabilities). Last year, even as Korea’s economy slowed, the government’s fiscal surplus rose to almost 2.75 percent of GDP. The IMF: “The structural budget surplus increased by 0.4 percentage point compared to 2017, to 2.9 percent of GDP. Net lending (consolidating central government and social security fund accounts) recorded a surplus of 2.7 percent of GDP in 2018”

Korea is the one country in the world that makes Germany look profligate in comparison.

Korea more or less sat out the coordinated fiscal expansion during the global crisis: its general government surplus went down to zero in 2009, but it quickly popped back up. Rather than supporting its own demand, Korea preferred to intervene heavily (at the time) in the foreign exchange market to support its exports.

President Moon has talked a better game than his predecessor; he wants to expand Korea’s limited social safety net and raise the minimum wage. But the IMF’s estimate of Korea’s actual swing in fiscal policy in 2019 is modest. Korea’s 2019 fiscal surplus—counting the massive surplus in Korea’s social security fund—looks set to remain close to 2 percent of its GDP.*

And well, Korea’s latest temporary “stimulus” package is a classic case of fake news. Its estimated economic impact is less than a tenth of a point of Korean GDP, and the bulk of it will be financed by the government’s excess cash from last year. Korea almost always does a temporary “stimulus” that modulates the excessively tight overall budget just a bit (the IMF “Since 2016, revenue outturns have been significantly higher than envisaged in the budget, widening budget surpluses, despite the introduction of supplementary budgets”). And this year’s temporary stimulus is smaller than last year’s temporary stimulus. It simply isn’t significant (though to be fair the overall budget isnn’t quite as tight as past budgets, so less depends on the size of the temporary stimulus).

The IMF has caught on—it’s (at long last!) clearly calling for the Koreans to do more. The U.S. Treasury, alas, has not. You would not know from reading the latest foreign exchange report that even after the latest stimulus Korea will retain a tighter fiscal policy than Germany.*

A weak economy means a naturally weak won— Korea hasn’t had to intervene in the foreign exchange market to limit the won’s appreciation (as it did in the past) with the market driving the won down.

But the combination of won weakness and a still tight budget also means that Korea hasn’t taken advantage of the pressure created by the latest global slowdown to introduce the policies needed for a more balanced overall economy. Even with a more left leaning government. That’s disappointing.

And in Korea’s case, the bulk of the overall government surplus—which comes from collecting more contributions to the national social security fund than the government pays out, while the headline government budget is close to balance—is channeled directly into the buildup of foreign assets. The national social security fund invests about half of its new inflows abroad, a policy that —as Matthew Klein of Barron’s notes, has a big impact on Korea’s overall pattern of trade. The pension fund’s large structural outflow has taken some pressure off the Korean central bank to intervene massively in good times.** And, well, in bad times it generates a quite weak won…

That brings me to my final point—one I have made before.

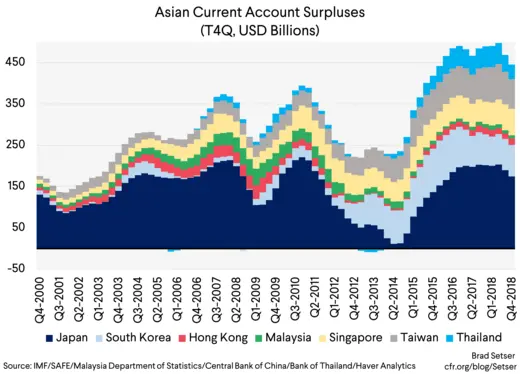

China’s overall external surplus is down. That’s not surprising—China’s general government deficit is somewhere between 4 percent of GDP and 12 percent of GDP, depending on what measure you use. The gap between China’s fiscal stance and that of Korea is even bigger than the gulf between Germany’s surplus and the deficit of France—and the gap between the euro area’s (tight) overall fiscal stance and the much looser stance of the United States.

But the surplus of China’s neighbors, who have responded, in many cases, to the “rise” of China with policy stances designed to maintain weak currencies and protect their exports, has soared over the past ten years, and now is substantially larger than it was prior to the global crisis.

The euro area’s post-crisis swing toward a large surplus has gotten more attention. But there has been a comparable swing in the Asian newly industrialized economies…

* The Treasury has long given Korea more credit than Korea deserved for temporary fiscal stimulus packages that were too small to move the needle, and that largely offset the impact of the previous year’s temporary fiscal package. In many cases, the actual surplus continued to grow—as the underlying budget was built around extremely conservative assumptions so a “temporary” stimulus was needed to avoid substantial tightening. There will be a real stimulus this year, unlike in past years. It is just too small, given Korea’s cyclical weakness.

** Korea now is disclosing its intervention over six months with a six-month lag. But the first disclosure didn’t really tell us much, in part because it shouldn’t be all that different from “balance of payments” reserve growth and in part because the period covered by the disclosure wasn’t marked by significant changes in Korea’s forward book. The next disclosure may be more interesting—as it should be close to the sum of the change in forwards and BoP reserves (conceptually, the “intervention” number should leave out interest income). It though is disappointing that Korea’s disclosure lags best practice globally—India, Russia, and Brazil all disclose more, and on a more timely basis.