Lebanon’s Imminent Financial Crisis

Lebanon is in a deep financial hole, with no obvious way out.

Lebanon doesn’t get much attention from the financial press.

Very little of its bonded debt (circa $10 billion) is in the hands of the broader international market; most is held by the local banks and the Banque du Liban (Lebanon’s central bank). And its economy—around $60 billion at an inflated exchange rate—is too small to really impact the global outlook.

But it is still a fascinating case of financial distress.

Lebanon’s fiscal and banking balance sheets are so interconnected that they make the euro area’s bank sovereign “doom loop” look modest. The banks do little other than lend to the government, either directly or through the central bank.*

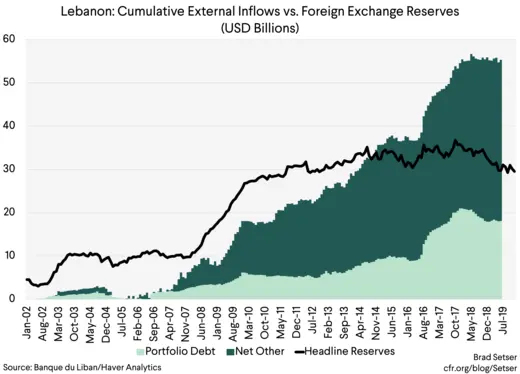

And there is good reason to think that Lebanon will not be able to defy financial gravity for much longer. The foreign currency deposit inflows that funded Lebanon’s current account have dried up.

A shortfall of dollars has led the banks to limit domestic depositor’s ability to access foreign currency (cash). Lebanon’s government has lost market access (maturing bonds are paid out of Lebanon’s shrinking reserves) and it has a set of three eurobonds maturing over the next few months.

Defaulting on the eurobonds increasingly looks to be the financially prudent option. Using stretched reserves to pay maturing bonds when the government has no prospect of repaying all its debts over time basically favors one set of claims on Lebanon’s limited foreign currency reserves over all other claims.

There are many important and interesting financial details. But at heart, Lebanon’s case is a simple one—

The government financed itself by selling bonds—mostly in dollars, but sometimes in Lebanese pounds (the pound is pegged to the dollar at 1505 Lebanese pounds to the dollar). It thus looked like it was financing its large fiscal deficit with relatively long-term money.

But it was mainly selling its bonds to Lebanon’s banks (and on occasion to the central bank).

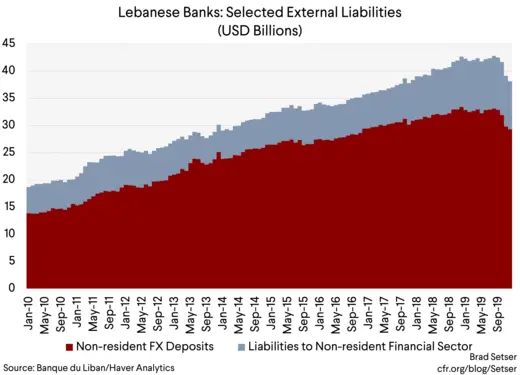

The banks in turn raised money from outside of Lebanon by offering very high deposit rates for dollars—and attracted a lot of domestic foreign currency deposits as well.

Those deposit inflows, together with modest foreign purchases of euro bonds, in turn covered the “twin” of the fiscal deficit—the external deficit (deposit inflows show up as “other” inflows in the balance of payments).

This went on for a long time—government debt is heading toward 160 percent of GDP (and that’s understated, as Lebanon’s currency is overvalued and much of the debt is in foreign currency and there may well be hidden losses at the central bank); external debt stands at close to 200 percent of GDP [pdf].

The net result was that the hottest of hot money—short-term dollar deposits, though often from Lebanon’s own diaspora—was financing Lebanon’s budget deficits, with a lot—and I mean a lot—of help from Lebanon’s central bank.

But the game could only go on for so long. It “worked” only as long as there were new inflows to finance the ongoing deficits (see Carlos Abadi in the Financial Times) and, well, even with a lot of machinations from the central bank the flow has dried up.

Reserves have been falling, or would be but for some funds that the Banque du Liban borrowed to juice its headline reserves.

Controls have effectively been put in place to limit deposit flight.

And the Lebanese government is now debating whether to pay a maturing $1.2b eurobond coming due in March.**

But these are all bandaids.

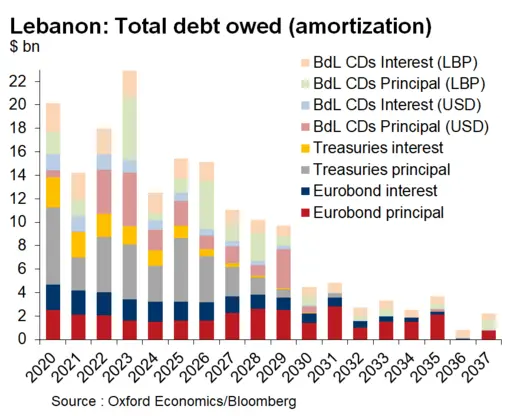

A large external debt is sustainable only if it carries a low interest rate, and Lebanon’s external debt is both short-term and high-cost. Similarly, the government’s large debt stock is only sustainable if it carries a low rate—and right now the government is paying interest of something like 10 percent of its GDP on a stock of 160 percent (the budget deficit is a function of interest, the primary fiscal account is close to balance—see the IMF staff report, Table 2a). The numbers don’t work, as interest payments are rising (to above 10 percent of GDP) thanks to the interest on funds borrowed to pay existing interest.

In a strange way though Lebanon is such an extreme case that it makes the solution conceptually clear—though the practicalities of carrying it out are all incredibly difficult.

The eurobonds (around $30 billion) clearly need to be restructured, sooner rather than later. The market is already pricing in a major restructuring (the long-dated bonds are trading at 40 cents on the dollar or less—and a lot of bonds don’t trade as they are stuffed away in the banks).

And banks are so intertwined with the government and the central bank that they also will need to be restructured (Fitch). That actually is the hard bit.

Iceland (see Benediktsdottir, Eggertsson, and Þorarinssonn and Þorsteinsson***) and Cyprus (see the IMF’s selected issues paper from 2014) are the relevant cases—though the analogies are imperfect, as the “bad” asset that is bringing down Lebanon’s banks is fundamentally the bank’s claim on the government.

But the banks need to de-lever externally. That can only be achieved with a joint restructuring of the banking sector’s external liabilities (the banks have $35-40 billion in external deposits and cross border liabilities, according to data from the Banque du Liban) and their main assets, namely claims on the government (and central bank) of Lebanon. Lebanon has too much external debt, and way too much short-term external debt (other flows are essentially bank flows, and they are short-term).***

So in broad terms, my guess is that external deposits need to be shifted to a set of bad banks, and the bad banks would receive a portion of the banks’ holdings of government bonds (they in theory should get the equity in the good banks, though I suspect that equity will be heavily diluted by the needed domestic bank recapitalization).

And then the deposits need to be converted into long-term, low interest rate bonds.

Back that plan up with a bit of financing from the international community if that is available. But such a gift to the depositors isn’t financially necessary, though it no doubt would make the bitter pill of deposit restructuring a bit easier to swallow (the international community would likely lend to the government to help fill the fall in reserves associated with any cash sweetener, not directly fund the payout, and to be honest, the best use of international funding right now is to help pay for essential imports and to help cover the cost of Lebanon’s large refugee community.

Basically, you cannot solve Lebanon’s unsustainable public debt without addressing its unsustainable external debt (too much external debt, at too short a maturity). And since the banks raised a lot of funds outside of Lebanon, that means restructuring—in some form—external claims on the banks.

This sets aside the challenges of operating a domestic banking system in dollars (the banks have $135 billion in “domestic foreign currency deposits” along side $45 billion in non-resident deposits—though I wonder if all “domestic” deposits really come from actual residents of Lebanon) when the country is short on dollar reserves.

And it ignores the complexities of how to handle the remaining “domestic” debt (claims on the central bank and the central bank) held by the “good” banks that will emerge out of any financial sector restructuring. Solving for external debt sustainability is insufficient to solve for public debt sustainability—it helps address the “flow” problem by reducing interest costs, but it doesn’t solve the underlying fiscal gap that will remain.

And it equally doesn’t solve the underlying political problem—all Lebanese governments are coalition governments and intrinsically fragile, and there is almost no more politically difficult task than allocating losses fairly.

Bottom line: I don’t see any realistic alternative to a broad restructuring of both the liability side of both the bank’s balance sheet and the sovereign’s balance sheet.

As an aside, there is active twitter discussion of Lebanon’s financial crisis—and some good old fashioned crisis blogging as well. Finance for Lebanon has quickly become a great resource for deciphering Lebanon’s economy and financial choices. They provide the color missing from the IMF’s staff report. Nafez Zouk of Oxford Economics also has done some excellent work.

There are also some massive unresolved questions about the Banque du Liban’s balance sheet. Its liabilities carry a high interest rate, and its assets either pay a low interest rate (the international reserves) or are claims on the government (some at very low interest rates). And since the government is effectively paying the Banque du Liban with funds it borrows from the Banque du Liban, there isn’t any real interest income coming in on its high yielding assets either. With a large share of its liabilities in foreign currency (notably dollar’s promised to the financial system), the central bank does need income (or it needs to restructure its liabilities). And the Banque du Liban has a massive balance sheet, holding just 100 percent of Lebanon’s GDP in external assets (counting a lot of gold) and another 100 percent of GDP (or more) in domestic assets—a mix of “securities” and mysterious “other” assets.*****

* “70 percent of their assets are invested in government bonds or lent to the BdL by buying Certificate of Deposits.”

** $2.5 bn maturing in three bonds are due in March, April, and June—and then there is a $2bn bond due in 2021 (Source).

*** With apologies for using international convention rather than Icelandic convention on the author’s names.

**** The IMF’s no longer so new reserve metric didn’t help the IMF identify Lebanon’s vulnerabilities. It suggested that Lebanon needed fewer reserves than it had short-term external debt (see the red line and compare it to the reserve metric bars on p. 28 of the IMF staff report). And since the IMF’s reserve metric puts the same weight on domestic foreign currency liabilities as domestic currency deposits, the IMF’s metric doesn’t highlight the potential reserve need from domestic dollarization. The reserve metric tends to understate the reserve needs of countries with large current account deficits and large external debts, and tends to overstate the reserve need of (typically Asian) economies with sustained current account surpluses and large domestic currency based banking systems. That is why the IMF in my view made a mistake by moving away from the more balance sheet based measures of reserve need (maybe that can be part of the MD’s new policy review?).

***** Lebanon, like Taiwan, doesn’t use the IMF’s reserve template for reporting its financial reserves. Taiwan likely hides its true asset position with limited disclosure—it uses swaps to move some of its foreign exchange reserves off its visible balance sheet. Lebanon almost certainly uses the lack of disclosure to hide the central banks true liability position, as the central bank almost certainly has more foreign currency debt (counting the foreign currency deposits it has taken in from the domestic banks) than liquid foreign currency assets. See Reuters.