Lessons from Tanzania’s Authoritarian Turn

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Michelle GavinRalph Bunche Senior Fellow for Africa Policy Studies

By Michelle GavinRalph Bunche Senior Fellow for Africa Policy Studies

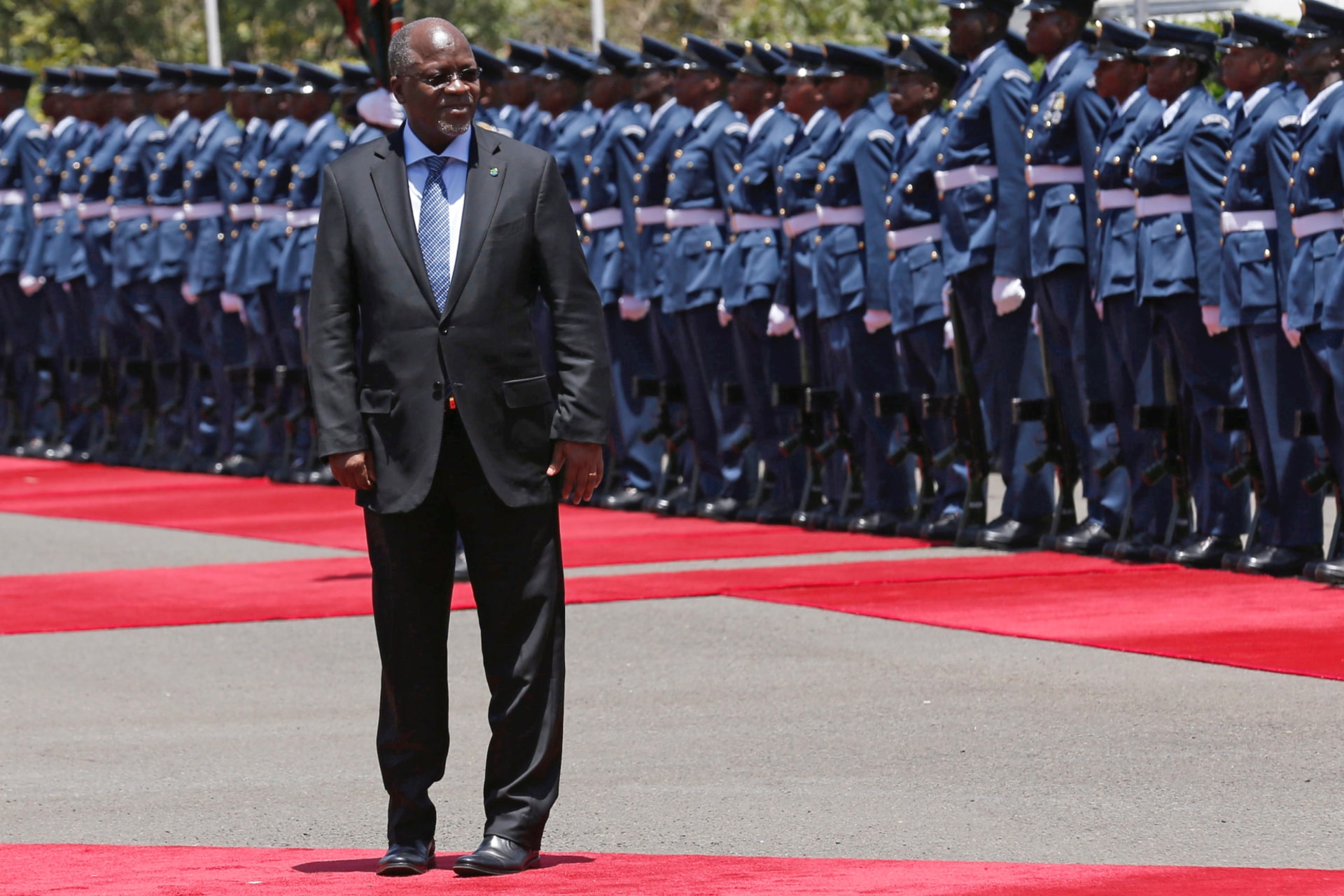

The alarming reports out of Tanzania have become commonplace. Current Tanzanian President John Magufuli, who swept into office on a popular anti-corruption platform, has been presiding over a shocking decline in political and civil rights in the country. Civil society leaders, opposition politicians, journalists, and businesspeople feel unsafe on their own soil—and with good reason. Crossing the regime can mean arrest on trumped-up charges, abductions, or extrajudicial violence. The legal environment has grown more and more draconian, shrinking political space, and limiting public access to information. Last November, the European Union recalled its ambassador to the country due to its concerns about the human rights situation, and the U.S. State Department issued a statement expressing deep concern about the “atmosphere of violence, intimidation, and discrimination” created by the Tanzanian government.

But until very recently, Tanzania was a development darling and a preferred African partner of the United States. Both symbolically and substantively, the United States invested in Tanzania’s success. President George W. Bush and President Barack Obama both made stops there. President Jakaya Kikwete, in office from 2005 to 2015, enjoyed Oval Office chats with both presidents as well. High-profile ambassadors were sent to Dar es Salaam—among them former congressman and current USAID administrator Mark Green. Tanzania was part of the first group of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) focus countries, and signed a Millennium Challenge Corporation Compact in 2008. The United States’ enthusiasm for Tanzania continued to be reflected in a number of Obama administration initiatives, including Feed the Future, the Global Health Initiative, Power Africa, and programs to promote maternal and child health. Despite a constant, low-volume rumble of concern about endemic corruption and some qualms about absorptive capacity, for years, the United States lavished attention and support on Tanzania in the hopes of cultivating a democratic development success story.

There are important questions to ask about how the Tanzania storyline changed so dramatically, so quickly. It certainly tells us something about the importance of leadership and tone at the top—a charismatic new leader can play a massively consequential part in changing a country’s trajectory for good or ill, as Ethiopia and Tanzania suggest. But Tanzania can also tell us something about how countries are primed for authoritarianism. When levels of frustration around service delivery and corruption reach a certain threshold, popular enthusiasm for a “bulldozer” who gets things done no matter who or what is crushed along the way can soar. This can lead to a society more and more dependent on the goodwill and honesty of the leader at the top, with few protections should those factors change or dissipate.

From donors’ perspective, decades of development investment are surely at risk when a state prohibits any questioning of its statistics or deviation from its preferred narrative. Tanzanian trends should tell the United States something about how we invest in perceived successes. Development never happens in a vacuum, and no state’s politics are set on perpetual autopilot. Perhaps the United States was too sanguine about the strength of Tanzanian democracy, and too quick to sweep warning signs, like repeated instances of repression in Zanzibar, aside in a desire to focus on development metrics. Under no circumstances does the United States of America determine the future of Tanzania, nor should it. But a keener sense of popular frustrations, and more support for civil society and democratic institutions, might have helped Tanzanians to protect their ability to hold their leaders accountable and chart their own course.