The Role of Peacekeeping in Africa

Updated

Africa continues to have more peacekeeping missions than any other continent. As conflict-stricken countries increasingly look outside the United Nations for support, experts say reforms are necessary to improve peacebuilding.

- Since 1960, there have been more than thirty UN peacekeeping missions across Africa, the most of any region.

- A growing number of security operations launched by regional blocs are playing increasingly crucial roles in peacekeeping efforts.

- Experts agree that peace operations help to protect civilians, but admit that they are flawed and that peacekeepers themselves can become part of the problem by committing sexual and other rights abuses.

What are backgrounders?

Authoritative, accessible, and regularly updated Backgrounders on hundreds of foreign policy topics.

Who Makes them?

The entire CFR editorial team, with regular reviews by fellows and subject matter experts.

Introduction

Today, more than fifty thousand troops are deployed for UN operations in Africa, and tens of thousands more deployed for regionally led missions in countries where civil wars and insurgencies have killed civilians and threatened to destabilize surrounding regions.

Many experts agree that peacekeeping missions help protect civilians and reduce some of the worst consequences of war, even as some critics say they are often deeply flawed and ineffective at creating lasting peace. Reports of sexual and other abuses by UN peacekeepers have drawn particular condemnation in recent years and prompted some reforms. Still, heated debate persists about how to make these missions more effective, such as by looking to non-UN initiatives to bring peace to conflict-stricken parts of Africa.

Where are peacekeepers deployed in Africa?

Roughly half of the UN peacekeeping missions operating around the world are in Africa. These include Abyei, an area contested by Sudan and South Sudan (UNISFA); the Central African Republic (MINUSCA); the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO); South Sudan (UNMISS); and Western Sahara (MINURSO).

Additionally, a growing number of peacekeeping or security missions under the auspices of regional blocs, such as the African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), have emerged as alternatives to traditional UN peace operations. The AU and regional partners currently oversee ten operations across seventeen countries, comprising more than seventy thousand personnel. The largest are the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) and the Lake Chad Basin Commission Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF). Most recently, in 2022, four African-led missions launched or revised their mandates in an effort to address worsening conflicts and support transitions to peace in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, and Somalia.

The European Union (EU) also plays a role, though its presence has dwindled due to rising tensions between African countries and former colonial powers. An EU counterinsurgency force led by France was pressured into withdrawing from Mali in 2022 after a military junta took over the Malian government, and several other efforts involving France in the Sahel have been met with hostility from the region.

Who oversees peacekeeping missions?

The United Nations is the preeminent body to authorize and oversee international peacekeeping missions. It generally follows three principles for deploying peacekeepers: main parties to the conflict should consent; peacekeepers should remain impartial but not neutral; and peacekeepers cannot use force except in self-defense and defense of the mandate. However, UN peacekeepers have been deployed to war zones where not all the main parties have consented, such as in Mali. Earlier this year, Mali and the DRC each formally requested that UN peacekeepers leave; withdrawal plans for both countries’ operations are currently in progress.

Under the UN Charter, the Security Council can authorize an operation with an affirmative vote of at least nine of its fifteen members and without a veto from one of the five permanent members (the United States, China, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom). The Security Council likewise must vote to renew peacekeeping operations when mandates are set to expire, typically each year.

The AU, which comprises all fifty-five African states, establishes peace operations when authorized by its fifteen-member Peace and Security Council. (The council has no permanent members.) The United Nations often gets involved in African-led missions as well. In the case of the AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), the United Nations authorized the AU mission and provided funding, logistics, and other support, until the Security Council authorized a reconfiguration of the mission in 2022 to establish today’s ATMIS. Similarly, the two major ad hoc security initiatives on the continent, the MNJTF against Boko Haram and the G5 Sahel’s force, were authorized by the AU and won the backing of the UN Security Council, strengthening their mandates.

What do peacekeepers do?

Peacekeeping mandates differ depending on the scope and scale of the conflict and on the body or group overseeing the mission.

The United Nations deploys peacekeeping forces to protect civilians in armed conflicts, prevent or contain fighting, stabilize postconflict zones, help implement peace accords, and assist democratic transitions. To achieve these goals, peacekeepers participate in a variety of peacebuilding activities, including:

- disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of ex-combatants;

- landmine removal;

- restoration of the rule of law;

- protection and promotion of human rights; and,

- electoral assistance.

Experts note, however, that over the years, UN peacekeeping mandates have become stretched and the responsibilities of peacekeepers sometimes blurred. “Rather than monitoring peace as agreed by conflicting parties as the UN did during the Cold War until the late 1980s, peacekeeping operations, such as MINUSMA and AMISOM, are effectively taking sides and engaging in a variety of activities, including protection of facilities and infrastructure, counterinsurgency and effective warfighting,” writes the University of the Free State’s Theo Neethling.

AU missions have similarly seen shifting goals. For example, AMISOM’s initial mandate, authorized by the AU Peace and Security Council and UN Security Council in early 2007, focused on the protection of Somalia’s transitional government. But the scope of the mission changed over time, later focusing on facilitating the transfer of security responsibilities to Somali forces while reducing the threat posed by al-Shabaab and other armed groups. The AMISOM replacement established in 2022, ATMIS, focuses on drawing down peacekeeping operations after fifteen years. Though in November 2023, the mission was extended through at least June 2024.

Meanwhile, the African-led peace initiatives operating outside the traditional UN framework have a wide array of mandates, such as working toward cease-fires or peace agreements, supporting elections, protecting leaders facing unrest, carrying out stabilization and counterinsurgency efforts, and combating health crises. The G5 Sahel Joint Force—seen as a supplement to MINUSMA and originally composed of forces from Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger—is mandated with combating terrorism, cross-border crime, and human trafficking in Sahel. However, Mali pulled out of the initiative in the wake of its 2020 military coup, and the military governments of Burkina Faso and Niger announced in December 2023 that they would also withdraw, leaving Chad and Mauritania to consider dissolving the G5 Sahel entirely.

How are they staffed and funded?

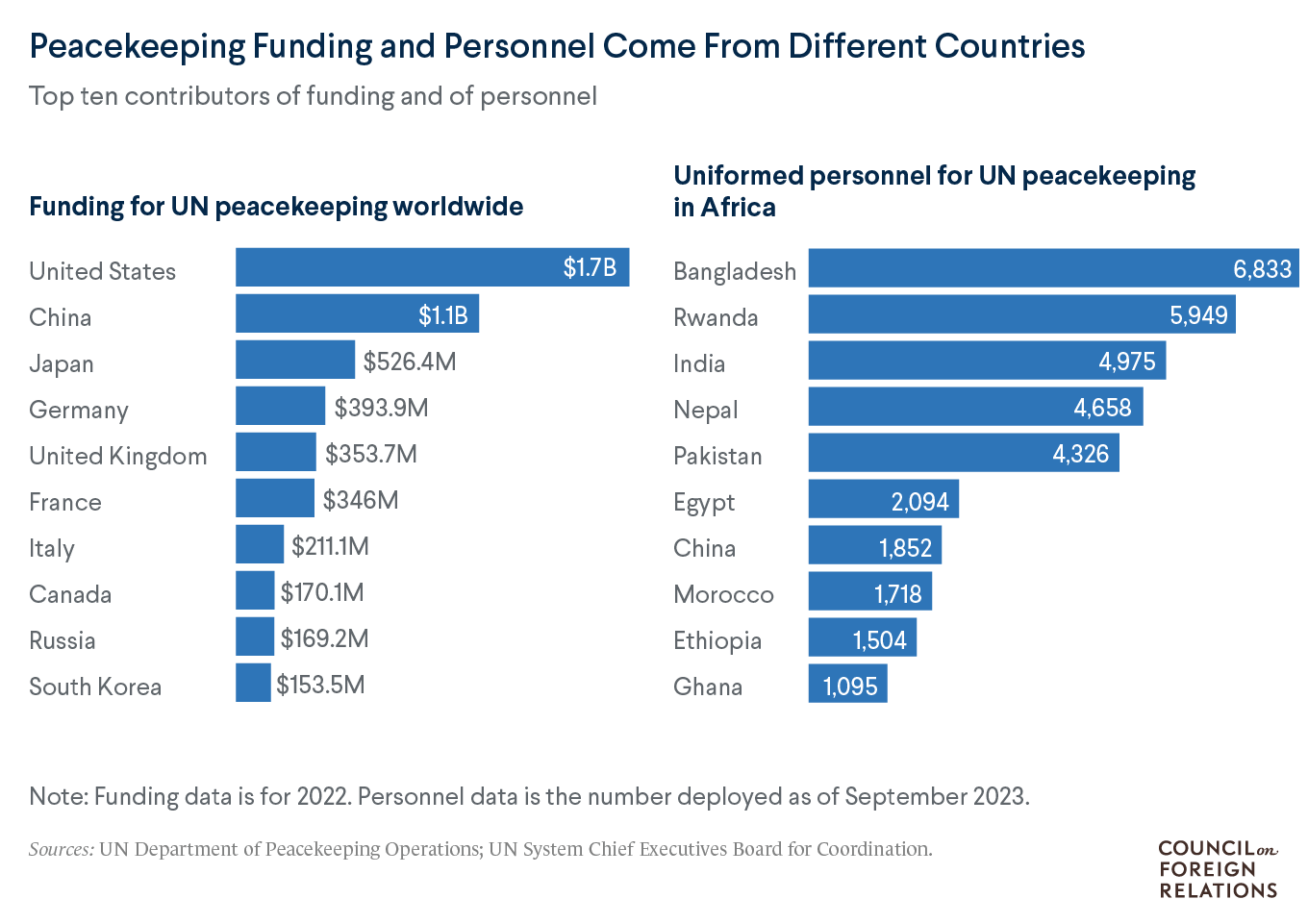

As of the end of 2023, Bangladesh, Rwanda, and Nepal were the top contributors of military and police forces for UN missions in Africa. The United States, China, and Japan are the top donors to the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations, whose budget, currently around $6.5 billion, is overseen by the UN General Assembly. By way of comparison, the U.S. defense budget was $1.5 trillion in the 2023 fiscal year. UN peacekeepers are paid by their own governments, which the United Nations reimburses, currently at a rate of roughly $1,400 per peacekeeper per month.

The disconnect between those nations that send troops and those that fund missions is often a source of tension. Wealthy nations spend the most on peacekeeping, yet they send relatively few troops; meanwhile, countries that either send troops or whose citizens are directly affected by peacekeeping missions often have less say in how they are designed and mandated.

Leaders in Africa and within the United Nations have called for African forces to play a larger role in securing peace and stability on the continent, but budget constraints persist. Unlike the United Nations with its regular peacekeeping budget, the AU has to continually seek out donors—such as the United Nations, the EU, and the United States—to fund its missions. In 2023, more than two-thirds of the AU’s budget was funded by international partners, not member states. In 2016, the AU launched a drive to increase member funding of security initiatives, but it fell far short of reaching its $400 million goal by 2020.

Are peacekeeping missions considered effective?

Modern peacekeeping marked seventy-five years of operations in 2023—the United Nations’ first peacekeeping mission launched less than three years after the global body was established in 1945. Over the years, these missions have made some tangible gains, but experts still differ on how to measure success: an improvement of the status quo, an accomplishment of the mandate, and an end to the conflict are among the possible benchmarks.

Africa is generally considered to have had mixed results with its UN operations, with a few considered more successful, such as those in the Ivory Coast, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. In Sierra Leone, a UN mission known as UNAMSIL was deployed in 1999 to help bring an end to the country’s nearly decade-long civil war through the implementation of the Lomé Peace Agreement. Observers credit the success of the mission to a number of circumstances, particularly the warring parties’ commitment to the peace process; a fitting mandate with sufficient resources to carry it out, including for the disarmament and reintegration of ex-combatants; and international support for the peace and accountability process. “It was imperfect, but it was widely considered to have done most of what it had been established to do,” says CFR’s Michelle Gavin.

However, if at least one party is not willing to cease hostilities, a peacekeeping mission is likely to face greater challenges, as has been the case in the Central African Republic (CAR) and the DRC. Similarly, good relations with the host state are crucial to carrying out a genuine peace process and political strategy. The MONUSCO mission in the DRC, for example, one of the largest and longest-running UN peacekeeping operations, has faced increasing scrutiny from Kinshasa over the years. The mission was initially deployed in 2010 to protect civilians and support the stabilization of the government as it clashed with rebel groups amid political instability. The ongoing conflict has displaced millions. However, the government has argued that UN troops have been reluctant to confront rebel groups, and civilians have protested what they describe as a lack of adequate protection and widespread sexual abuse by soldiers. The mission has become so unpopular that in September 2023, President Félix Tshisekedi asked for it the UN to withdraw a year in advance. Eastern Congo’s troubles led Kinshasa to invite further regional intervention efforts, though the conflict continues.

On a broader scale, researchers have sought to assess the benefits of peacekeepers on the ground. Georgetown University’s Lise Howard, for example, has found that peacekeepers correlate with fewer civilian casualties, and that more peacekeepers—particularly more diverse peacekeepers—parallels both with fewer civilian deaths and fewer military deaths. One group of experts modeled scenarios with and without intervention and found that peacekeeping missions are ultimately a cost-effective measure whose contributions toward mitigating conflict and preventing spillover are often underestimated.

Some experts argue that those who see peacekeeping as costly often do not consider the costs avoided through their operations. The U.S. Government Accountability Office reported that financially supporting UN peacekeeping would be eight times more cost-effective for the United States than directly sending U.S. troops to a conflict zone.

What are the major criticisms?

UN peacekeeping missions on the continent have been criticized for a wide range of problems, including mismanagement, failure to act when civilians are under threat, rights abuses by peacekeepers, and financing troubles. But oftentimes at the core of missions’ faults, experts say, are broad mandates that are difficult to implement.

“The topic that comes back again and again is realistic mandates,” says Gavin. “How realistic is it to ask MONUSCO to protect civilians in the DRC, for example, given the geography and difficulties of moving through that terrain? How sustainable can civilian protection efforts be in the absence of a productive relationship with local authorities?”

Peacekeepers have come under fire for failing to intervene at critical moments: A 2014 report [PDF] by UN internal investigators found that peacekeepers globally only responded to one in five cases in which civilians were threatened and that they failed to use force in deadly attacks. One of the most cited failures on the African continent is the United Nation’s failure to prevent the 1994 Rwandan genocide despite the presence of peacekeepers on the ground. More than eight hundred thousand Rwandans were killed in a span of one hundred days. Despite some reforms in recent years, failures to protect civilians continue, the Economist reported, in large part due to restrictions by troop-contributing countries on how their peacekeepers can be used. Additionally, a 2021 internal evaluation found that peacekeeping staff perceive the level of ethics and integrity to be low and that accountability for misconduct is low.

Peacekeeping forces have also been accused of committing human rights abuses, including pervasive allegations of sexual abuse and exploitation. The United Nations disciplined several MONUSCO soldiers over allegations of sexual exploitation and violence in 2023. Two years earlier, the United Nations withdrew hundreds of Gabonese peacekeepers from CAR and opened a probe following allegations of sexual abuse of girls. Though UN investigations into such allegations have increased in recent years, very few lead to prosecutions and none has resulted in a public conviction. (UN peacekeepers have immunity from prosecution in the countries where they are deployed, leaving their home countries to undertake legal action.) A newly approved Kenya-led peace mission to mitigate gang violence in Haiti has raised concerns even before being deployed due to a history of abuse within Kenya’s police force.

Other critics argue that peacekeeping missions are too costly given their mixed success, and that they are too reliant on funding from a few major donors. The Donald Trump administration reinstated a cap on annual U.S. contributions to UN peacekeeping and sought additional, massive cuts to major operations in Africa. President Joe Biden has reversed those cuts and agreed to pay the $1 billion the United States owed in peacekeeping debt. Meanwhile, China has boosted its support in recent years, including by launching a ten-year, $1 billion fund for peacekeeping operations. Still others point out that the veto power of the Security Council’s permanent members can delay or weaken peacekeeping mandates, such as in Sudan’s Darfur region.

What are the prospects for reform?

Some reforms are underway at the United Nations. In 2018, UN Secretary-General António Guterres launched the Action for Peacekeeping (A4P) initiative, which focuses on developing more targeted peacekeeping mandates with clear political strategies, improving the safety of peacekeepers as well as civilians in mission areas, and better training troops. In tandem, the Security Council unanimously adopted a resolution aimed at improving leadership and accountability in peacekeeping, in response to the reports of sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeepers. However, it remains to be seen whether A4P is translating into concrete change. Meanwhile, experts note that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the urgency to undertake the kind of reforms outlined in A4P.

Given the proliferation of ad hoc initiatives, the Institute for Security Studies’ Gustavo de Carvalho argues, the United Nations should more closely coordinate with the AU and regional blocs to complement one another and avoid unnecessary overlap in their missions. With African personnel increasingly filling the demand for peacekeepers, Nadine Ansorg and Felix Haass of the German Institute for Global and Area Studies stress the importance of countries with advanced militaries helping to train and equip troops. Other experts see promise in supporting additional regional-led missions, believing them to be more adaptable. At a UN Security Council meeting on peace in Africa in May 2023, Secretary-General Guterres called for a “new generation” of AU-led operations financed by UN member nations, a model that African leaders have increasingly advocated for.

Other analysts encourage inclusivity. Former CFR Fellows Jamille Bigio and Rachel Vogelstein have advocated for more women peacekeepers, whose participation has been shown to improve missions’ effectiveness.

Moreover, many experts urge major powers to do more than bankroll missions. Victoria K. Holt of the Stimson Center and Jake Sherman of the International Peace Institute argue that the Biden administration should use the United States’ permanent seat on the Security Council to ensure that missions are tailored to their environments; guided by clear, inclusive political strategies; and take into account challenges such as climate risks.

Recommended Resources

The Congressional Research Service lays out the issues around U.S. funding of UN peacekeeping missions [PDF].

Nate D.F. Allen of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies assesses the security benefits of African-led peacekeeping missions, and the prospects for their reform.

The Associated Press’s Edith M. Lederer covers the seventy-fifth anniversary of UN peacekeeping, looking at its successes, failures, and challenges in its next chapter.

For World Peacekeeping Day, SecurityWomen contributor Alice MacLeod names ten reasons why women are crucial to peacekeeping.

CFR’s Global Conflict Tracker offers guides to the conflicts in the CAR, the DRC, Mali, Somalia, and elsewhere.

For the Conversation, Kirsten Wagner unpacks sexual exploitation in the DRC by UN peacekeeping personnel.t

Colophon

Staff Writers

- Claire Klobucista

- Mariel Ferragamo

Additional Reporting

Danielle Renwick contributed to this article, and Michael Bricknell and Will Merrow helped created the graphics for this Backgrounder. Header image by Djaffar Sabiti/Reuters.