North Korea’s Food Situation: Stable and Improving

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Scott A. SnyderSenior Fellow for Korea Studies and Director of the Program on U.S.-Korea Policy

When asked in his January 22 interview with YouTube [9:00 ff.] about the likely effects of greater sanctions on North Korea following the Sony hack, President Obama repeated a mantra widely associated with North Korea that as a result of its isolated, authoritarian leadership, “the country can’t really even feed its own people” and that “over time, a regime like this will collapse.” But the latest reports show that North Korea’s food situation is stable, and the leadership probably thinks it is doing better, not worse.

The UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) released its latest assessment of the situation in North Korea on February 3, 2015. The nature of the assessment differs from assessments of previous years in that it relies solely on DPRK figures supplemented by additional observations based on FAO satellite analysis and educated judgments regarding DPRK production gathered through past experience inside the DPRK, but the report does not benefit from information gathered during past on-the-ground food security assessment missions. These missions had been taking place annually through the fall of 2013 but the mission did not occur in the fall of 2014.

The fact that the DPRK decided not to continue to host an annual UN FAO field assessment is double-edged. On the one hand, the failure to approve the mission itself provides confirmation that DPRK authorities are increasingly confident in their improved food security situation. The DPRK appears to have made steady progress in domestic production in recent years, but at the same time growing income inequality in North Korea has resulted in continuing malnutrition among some sectors of the population, especially in rural areas. On the other hand, the decision to cancel the food assessment mission in 2014 leaves the FAO reliant on a combination of technical tools and information voluntarily provided by the government of the DPRK for the information used to make its assessment of the food situation in the DPRK. Over time, the quality of the assessment could be degraded without the opportunity to supplement these observations with local experience gained through physical visits to various parts of North Korea.

The bottom line of the FAO assessment is that North Korean food production has “remained stagnant” in 2014 at 5.94 million tons compared to the 5.93 million tons realized in 2013-2014. (This result was 50,000 tons below the FAO projection of 5.98 million tons released in November of 2013.) The FAO report projects a poor winter wheat and barley harvest in the coming months, but this harvest represents only about 10 percent of North Korean overall production. Even with this poorer than expected result, the FAO anticipates that the DPRK will need to import 407,000 tons of cereal to meet its overall need.

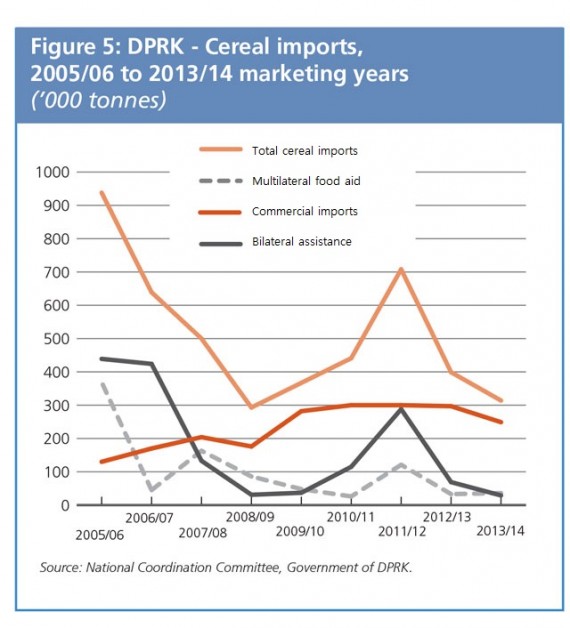

The 2013 FAO report had projected a cereal import requirement of 340,000 tons for 2013-2014. This amount is 8 percent greater than the actual amount of DPRK imports (313,755 tons) reported during that period. DPRK commercial cereal imports during this period included 248,603 tons of wheat flour from China. In addition, food aid to the DPRK declined “significantly” to about 65,152 tons of cereals.

Interestingly, according to this year’s report the Russian Federation surpassed China as the largest bilateral donor to North Korea in 2013-14 with 28,700 tons of wheat, followed by China with 8,300 tons of maize. Multilateral cereal food assistance rose by almost 10 percent to 36,385 tons in 2013-2014. The attached chart from the report shows the substantial reduction in DPRK cereal imports to around 300,000 tons from about one million tons of assistance required in the aftermath of North Korea’s famine in the mid-2000s. It also shows North Korea beginning to meet its production shortfalls through commercial procurement rather than reliance on international aid.

The FAO assessment of North Korean food production is consistent with anecdotal reports that North Korea has made productivity improvements in recent years and that the North Korean economy is stable if not growing slowly. Andrei Lankov reports on the basis of defector interviews that a number of the agricultural and market reforms made under Kim Jong-un appear to be taking hold. This means that North Korea’s two-pronged policy of simultaneous economic and nuclear development is showing some modest results on the economic side. The problem is that the nuclear priority remains in place and North Korea’s efforts to develop missile and nuclear programs continues to proceed unchecked.

North Korea’s apparent economic progress is bad news for those who expect increased sanctions to be decisive in driving North Korea to make a strategic choice to give up its nuclear weapons. So far, the effects of increased sanctions have been far from generating sufficient economic pressure to induce North Korea to make such a choice. Under current circumstances, there is nothing to stop North Korea from having its cake and its yellowcake, too.