PM Kishida’s Election

October 31 offered the Japanese people the opportunity to weigh in on their new prime minister, Fumio Kishida, and his party, the Liberal Democrats.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Sheila A. SmithJohn E. Merow Senior Fellow for Asia-Pacific Studies

By Sheila A. SmithJohn E. Merow Senior Fellow for Asia-Pacific Studies

October 31 offered the Japanese people the opportunity to weigh in on their new prime minister, Fumio Kishida, and his party, the Liberal Democrats. Despite the media attention, only 55.9% of Japan’s eligible voters turned out. But that was enough to demonstrate the LDP’s staying power, and provide the new prime minister, Fumio Kishida, with a stronger hand as he sets out to govern Japan.

When he called the election for October 31, Kishida claimed that he would be happy with the most minimal of wins, a simple majority for the LDP and its coalition partner, the Komeito. But he got far more than that. The LDP garnered a simple majority on its own with 261 of the 465 Lower House seats. This not only allows the LDP-Komeito leaders to claim a solid victory, but it also puts the LDP in a discerning position within the Diet. Japan’s conservatives can now run the Diet committees and shape the legislative agenda going forward.

Most of all, Prime Minister Kishida won an election that many in his own party worried they might lose. To be sure, the LDP came out of the election with 15 fewer seats, but that was a far smaller number than anticipated.

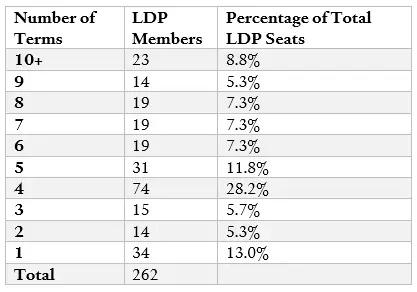

Source: Compiled based on information available from Japan’s House of Representatives website. This information, which was not initially available when this blog was published, was updated on 11/23/21.

Those who had come into office during the three Abe elections of 2012, 2014 and 2017 had represented 46% of the party going into the election, and 23 of these 126 candidates lost their seats. Kishida added 34 freshmen legislators to the LDP ranks in this election, but even with these new faces, the share post-election of LDP Diet members with three or fewer terms represents only 25% of the party.

Tough Single Member Outcomes

But the LDP’s elders were not safe either in their tough-to-win single member districts. Five veteran lawmakers from the LDP were defeated in their home districts, some by conspicuously young challengers. Some notable losses drew media attention. Nobuteru Ishihara lost his seat in Tokyo’s tenth District and was unable to return via the party’s proportional list. Harumi Yoshida, a female candidate from the CDPJ, took his seat. Takeshi Noda, a longtime party stalwart, also went down to a younger candidate in Kumamoto’s second district. Former Minister of the Environment Yoshiaki Harada (Fukuoka 5), and former Minister of Regional Revitalization Kozo Yamamoto (Fukuoka 10) lost their seats as well. Perhaps the most stunning defeat was that of Akira Amari, the party’s newly appointed secretary general. In his thirteenth term, Amari is the first sitting LDP Secretary General to lose an election. Amari was resuscitated via the LDP proportional list but resigned his party role. Kishida is expected to appoint Toshimitsu Motegi, the foreign minister, to the Secretary General post.

This changing of the guard was visible among opposition lawmakers as well. Ichiro’s Ozawa inability to win his Iwate seat stunned political observers, as Ozawa’s fame for destroying his competitors and navigating electoral dynamics is renowned. He was easily the most influential of Japan’s politicos during the 1990s, the transformative decade of political reform that paralleled the end of the Cold War. It was Ozawa that guided the discussion between Tokyo and Washington on the response to the first Gulf War. It was Ozawa who, by leading an exodus from the LDP in 2012, created the complex party realignments that followed. And it was Ozawa that brought his legendary electoral skills to the opposition Democratic Party of Japan that contributed to its win in 2009. For so long, Ozawa’s star shone brightly – if not always consistently – across the spectrum of Japanese politics. But in this election, he had to be brought back in by the CDPJ on their party list.

Clearly this was not a good election for Japan’s opposition parties. They had a short time to campaign and their strategy of preparing a unified candidate list among the left-leaning parties did not lead to electoral gains. The Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ), the Democratic Party for the People (DPP), the Japanese Communist Party (JCP), Reiwa Shinsengumi, and the Social Democratic Party (SDP), did not garner momentum, and the LDP campaigned heartily against the CDPJ’s alignment with the JCP. Of the 213 candidates on that list, only 59 won. Particularly hard was the outcome for the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan, which went from 110 to 96 seats. Party leader Yukio Edano had a tough fight in his own district, as did former prime minister, Naoto Kan. Nonetheless, the CDPJ remains the second largest party in the Diet. Edano and the Secretary General Tetsuro Fukuyama resigned from leadership to allow a new strategy for the Upper House elections to take shape.

Only the Nippon Ishin no Kai, an Osaka-based rightist party, did well, growing from their dismal 2017 outcome of only eleven seats to occupy forty-one seats. This makes Ishin the third largest party in the Lower House, after the LDP and the CDPJ. More information may be needed at the district level but there is no doubt that it was the conservative Osaka-based party that benefitted from LDP losses.

A Glimpse of Social Change?

The LDP win last Sunday should not ignore some important indicators of social change in Japan. Japan’s independent voters largely stayed home from this election, and thus party stalwarts carried the day. The Asahi Shimbun captured an important insight in its exit poll when it asked voters which party they chose for their proportional vote. Across age groups, the LDP party list attracted about 35-40% of respondents, but the demographics of those who claimed to support the leftist political parties was heavily skewed towards older voters. In other words, voters who are loyal to parties on the left are aging, and while younger voters may still be inclined towards issues that are more socially liberal, they may not identify themselves as loyal to old guard leftist parties.

Two new campaign issues this fall revealed Japan’s shifting social mores: the legal right for a woman to retain her family name after marriage and recognition by the state of same-sex couples. Interestingly, these two issues were in the mix for the LDP leadership race, with two of the four candidates (Seiko Noda and Taro Kono) in the conservative party reflecting more liberal social views. But in the general election, it was Japan’s opposition parties that took up the mantle of advocating for a more inclusive society. Nonetheless, with only 43% of younger Japanese turning out to vote, national politics still does not offer a compelling venue for these issues despite local municipal policy change and judicial activism. Furthermore, the inability of the Japanese political system to reflect women cannot be ignored. In one of the biggest disappointments of this election, the number of Japanese female legislators went down, from 10.0% to 9.7%, a far cry from the government’s goal of 30.0%.

Choosing Stability

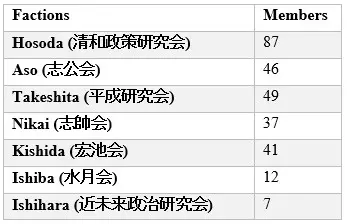

Prime Minister Kishida’s wins from this election are twofold. First, he can now feel confident in his leadership of the party with a relatively sound electoral victory behind him. Moreover, if he can continue to bring new faces into the party’s leadership he can balance the competing generational interests of party elders and the up-and-coming younger generation. Nonetheless, Kishida will need to have the support of the Aso faction, which along with his own, balances the might of the Hosoda faction that includes Abe.

Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, 11/3/21

Second, the Kishida Cabinet now has a stronger chance at implementing its policy agenda. With a focus on economic recovery from the COVID pandemic, Kishida and his party have emphasized the need to ensure that Japan’s economic growth is more evenly distributed. Here the LDP and Komeito are largely in agreement, and Japanese businesses will be included to cooperate in the effort to allow Japanese households to share in the economic recovery. Masakazu Tokura, the head of the Keidanren, congratulated Kishida on the victory and promised to work with him to ensure wage increases for Japanese families. Notably, however, Tokura also stated that Japan’s economy is a global one and cautioned that “its doors must not be closed.” On the security side of Kishida’s agenda, the electoral outcome supports stronger Japanese defenses. Here, not only the LDP and Komeito but also Ishin no Kai’s added seats will ensure that any defense reforms, including increasing Japan’s defense budget, will have majority support.

But still, Japan’s new prime minister has some hurdles ahead. First, an Upper House election looms next summer and this will diminish the likelihood that the Kishida Cabinet will tackle difficult or divisive policy initiatives. Second, Japanese citizens will want to see their economic prospects brighten, and Kishida has promised them a larger share in Japan’s economic growth. Finally, the world outside will keep Japan’s prime minister on his toes. There are some difficult national security choices ahead for Tokyo, and Kishida will have to make sure his country not only is secure, but also that it has an active voice in the Indo-Pacific coalition forming to ensuring that the region remains “free and open.”

Japan’s voters may not have turned out in overwhelming numbers, but those that did endorsed the status quo, the continued leadership of the conservative party. Many of the single member districts in Japan’s electoral system were closely contested, and the opposition now must go back and reconsider its electoral strategy going forward. While not a reformist referendum, the loss of some of Japan’s most seasoned politicians – both on the left and on the right – suggests that those who imagined a new style of Japanese politics after the 1990s are fading from the scene. What PM Kishida’s generation and their successors will now create remains to be seen.