Risk Aversion Is at the Heart of the Cyber Response Dilemma

Western countries view the cyber domain as a highly uncertain and potentially escalatory environment, which takes more forceful response options off the table.

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Guest Blogger for Net Politics

Monica Kaminska is a postdoctoral researcher at the Hague Program for Cyber Norms, Institute for Security and Global Affairs at Leiden University and a PhD candidate in Cyber Security at the University of Oxford.

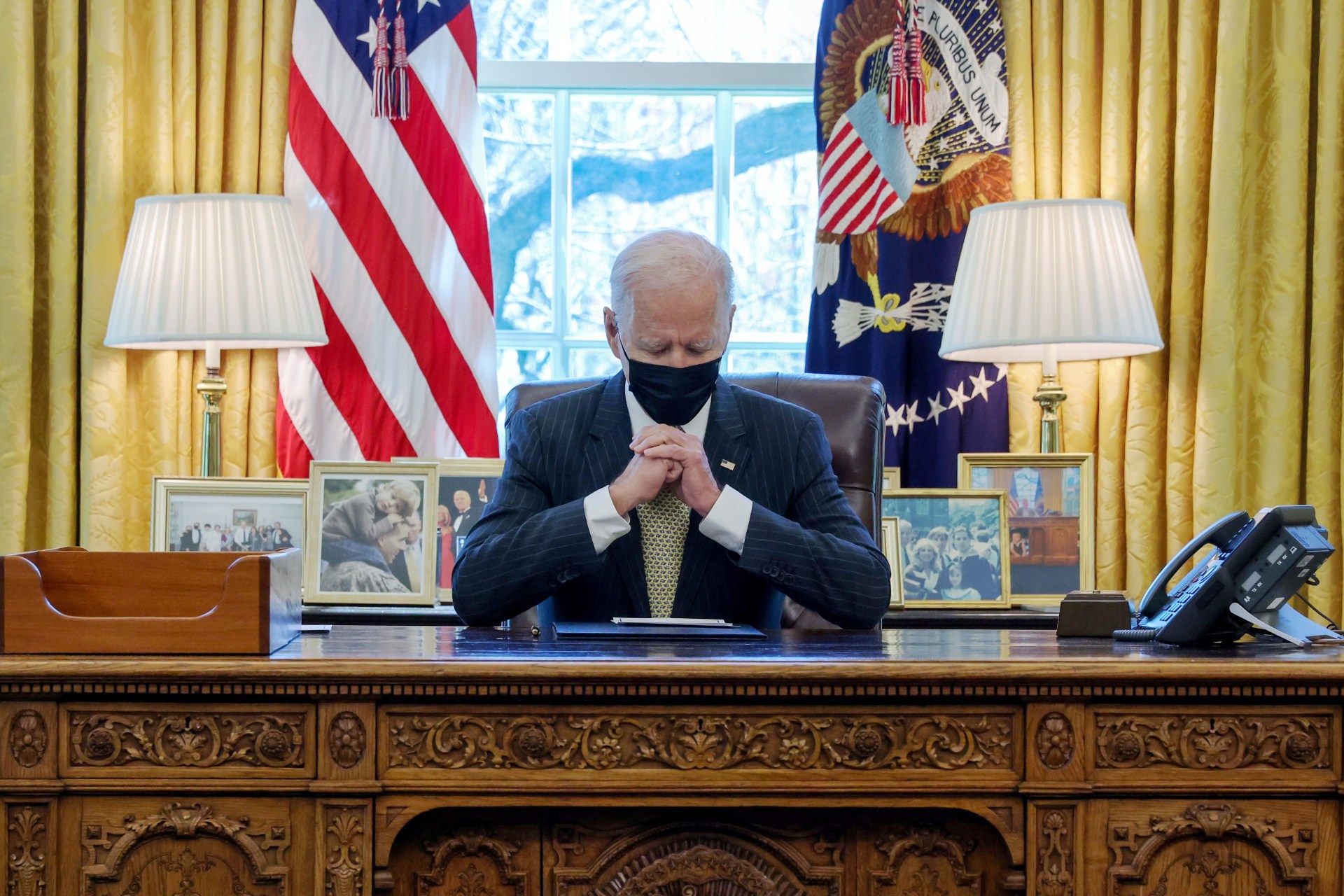

The New York Times recently received swift pushback from the White House against a claim that it was preparing a “cyberstrike” against Russia in retaliation for the SolarWinds/Sunburst campaign. The Biden administration’s desire to tone down such rhetoric is not a surprise. Although the SolarWinds campaign appears to have been limited to espionage, the kind which the Five Eyes doubtlessly engage in themselves, meaningful and commensurate responses have proven difficult for the United States, even in the context of more disruptive or destructive cyber operations.

The question is why the United States restrains its responses, despite formally adopting a strategy of deterrence [PDF] and despite the wide set of economic, political, and cyber tools at its disposal. In a recent publication, I argue that the cyber domain is viewed as a highly uncertain and potentially escalatory environment, which takes more forceful response options off the table. The recent introduction of the strategies of persistent engagement and defend forward stems not from a shift to a more offensive approach but is instead an extension of the culturally engrained concern to limit uncertainty and risk.

The Problem With Current Responses

The United States’ usual recourse has included economic sanctions, legal indictments, and public attribution statements—or some combination of these instruments. However, the precise policy objective of imposing “risks and consequences” through them is often unclear. Sanctions and indictments tend to target a number of individual hackers for a variety of incidents, which confuses the signal they intend to deliver to the seats of power in Moscow and Pyongyang. Take, for example, the Justice Department’s October 2020 indictment of individuals for their cyber interference in Ukraine, Georgia, the French presidential elections, investigations into the Russian Novichok attack, and the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympic Games. The indictment was responding to hacks that ranged from intrusions into electrical grids to “hack and leak” election interference. The adversary could be forgiven for thinking they were being punished for the means used rather than for the operation’s intent or effects.

Economic sanctions can be an inconvenience—although the perpetrators of the most brazen cyber campaigns tend to be some of the most heavily sanctioned regimes on earth, which lessens the impact of new measures. In fact, the blowback effect of sanctions can sometimes mean that they have a greater effect on the sanctioning government than on the sanctioned one. For example, in 2018, the Trump administration was forced to back down from sanctions it imposed on Rusal, a Russian company, after they caused a spike in aluminum prices. Public attribution, for its part, has the objective of clarifying “the rules of the game” in cyberspace but in reality could even be seen as a badge of honor by some of the agencies to which the operations are traced back.

The “Risk Society” and the Roots of Restraint

Writing in the early 1990s, German sociologist Ulrich Beck coined the term “risk society” to describe a society defined by the anticipation of catastrophe, stemming from an awareness of the unintended side effects of modernization. The Chernobyl nuclear incident, global financial crises, transnational terrorism, and mounting evidence of environmental degradation generated a realization that geographic distance no longer offered protection from far-flung disasters and hazards. Moreover, these disasters and hazards were increasingly understood to be self-inflicted—the price that modern societies paid for progress.

This led to the development of the risk society—a pervasive sense of insecurity and fear, born of uncertain future events, that underpins policymaking and strategic thinking. The major trauma of the 9/11 terrorist attacks only served to cement this attitude. In a risk society, each decision is carefully weighed up between the costs of action versus inaction, often resulting in either overzealous pre-emption or paralysis. This new stage of modernity has not, however, affected every society equally. Beck reminds us that risk is culturally framed. Thus, different societies have different risk thresholds.

The Risk Society Goes Cyber

The complexity of the cyber operational environment and the United States’ dependency on internet-connected systems and networks means that it feels asymmetrically vulnerable to cyberattacks. Modernization, as Beck explained, has produced unanticipated and unintended side effects. The awareness of this asymmetric vulnerability features front and center when U.S. decision-makers face the dilemma of how to respond to foreign cyber aggression. Fearful of blowback from their own response or of triggering a cyber tit-for-tat exchange and unintentionally escalating a conflict, they opt instead to employ weaker measures. Domestic publics support such an attitude according to recent survey research. Adversaries are aware of these dispositions, so risk aversion poses a problem for the credibility of deterrent signals.

To address the uncertainties inherent in cyberspace, the United States has opted for risk management practices. These practices do not substitute for the imposition of costs in response to damaging adversary actions, but instead seek to mitigate as much as possible the scale and effects of hostile cyber operations on digital infrastructures.

Particularly notable have been the preventive practices of persistent engagement and defend forward, which aim to proactively “counter attacks close to their origins” in order to “render most malicious cyber and cyber-enabled activity inconsequential [PDF].” In adapting to the cyber domain, U.S. Cyber Command has shifted from being a “response force” to a “persistent force [PDF].” While on the face of it persistent engagement could seem like a more assertive and offensive strategy, it is in fact an outgrowth of the same aversion to risk that produced limited responses—which could seem paradoxical to those in the academic community who have expressed concerns about the strategy’s escalatory potential. By aiming to eliminate potential threats before these reach the homeland, persistent engagement implies the non-acceptance of adverse consequences of potential hostile campaigns and involves constantly surveilling foreign networks and anticipating the actions of adversaries to mitigate risks.

In noting the presence of the guiding risk paradigm informing the American cyber response calculus, we should not expect significant retaliation. In fact, it could be the case that deterrence strategies are simply incompatible with Western risk dispositions towards retaliation.