Shoals Ahead for the United States and India?

More on:

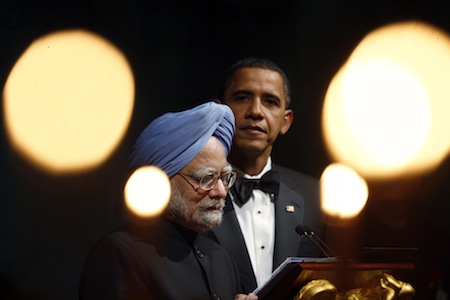

Manmohan Singh has come and gone, but his visit to Washington last month leaves several questions unanswered about the future of U.S.-India relations. Comparisons to Singh’s 2005 White House visit were inevitable—and that would have been a tough act to follow, by any standard. In 2005, Singh and George W. Bush launched the civil nuclear negotiation that cleared away perhaps the highest hurdle to closer U.S.-India relations. Obama and Singh did nothing so dramatic. But the good news is that both leaders recommitted their governments to an expanded U.S.-India partnership. As Sanjaya Baru, editor of India’s Business Standard, has put it, the joint statement that came out of this summit “was about all the other paragraphs” of the 2005 Bush-Singh statement—that is, “other than the famous paragraph on the nuclear deal.”

Obama and Singh issued a comprehensive Joint Statement focused on many of these other areas of cooperation, including defense, trade, energy, environment, education, and agriculture cooperation. But sustaining momentum in those areas won’t be as easy as it sounds. Just take trade, where the two sides began work toward a bilateral investment treaty in 2008 but negotiations stalled. The United States is India’s largest trading partner in goods and services, but India is America’s number 18 trading partner in goods, in a league with countries as small as Belgium and Ireland.

Still, the bigger challenge will be to manage looming disagreements on five potentially divisive strategic issues: the Obama administration’s “AfPak” strategy, China policy, arms control objectives, climate change priorities, and high technology cooperation. Obama’s recommitment to Afghanistan and the deployment of 30,000 additional U.S. troops should reassure some in India who view the fight in Afghanistan as a test of American staying power in South Asia. But there may be more difficult tests over the next 18 months. Indians will continue asking three questions, in particular: (1) Will Washington apply sustained pressure on Pakistan to crack down on groups and individuals that target India? (2) Can it resist the temptation to link American priorities in Pakistan’s tribal areas to India-Pakistan relations? And (3) Can it also resist the temptation to insert itself into the competition over Kashmir?

Then there is China. Obama’s China policy is broadly consistent with those of seven previous U.S. administrations since Richard Nixon. But China’s weight has grown over the past five years to the degree that many in India increasingly fear a U.S.-China condominium on issues of direct importance to India. Like Europeans and Japanese, Indians have become increasingly sensitive to suggestions that the United States looks to address global issues bilaterally with China, fearing that this will sideline New Delhi and work against Indian interests. And Indians are asking whether the United States envisions a role for India in maintaining a balance of power in Asia, and if the administration views India as important to U.S. priorities in East Asia.

Other differences loom over ams control, climate, and high technology cooperation—divisive issues all. The challenge will be to manage U.S.-India disagreements toward compromise, if not consensus, without finger-pointing or the old acrimony reemerging.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store