TWE Remembers: The OAS Endorses a Quarantine of Cuba (Cuban Missile Crisis, Day Eight)

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

By James M. LindsayMary and David Boies Distinguished Senior Fellow in U.S. Foreign Policy

The first week of the Cuban missile crisis played out in secret. President John F. Kennedy and his advisers quietly evaluated the results of the U-2 overflights and formulated a response. But on Tuesday, October 23 the crisis began playing out in public. U.S. diplomats scrambled to secure international support for the impending quarantine of Cuba while the White House waited to see what Moscow’s next steps would be.

The Organization of American States (OAS) met at 9:00 a.m. in emergency session at its headquarters in Washington, DC at the request of the United States. Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Edwin Martin introduced a resolution authorizing OAS members to use force, individually or collectively, to impose a quarantine on Cuba. The initial discussion proceeded slowly, however, because many of the ambassadors were awaiting instructions from their home capitals on how to vote. When the vote was finally held in late afternoon, every country but Uruguay voted yes. (Cuba had been expelled from the OAS earlier in the year, and the Uruguayan ambassador abstained because he still had not received instructions from Montevideo; the next day he would revise Uruguay’s vote to yes.) The United States now had what it claimed was a firm legal basis for imposing the quarantine.

News of the OAS vote reached New York while Adlai Stevenson, the U.S. ambassador to the UN, was addressing the Security Council. Kennedy and several of his advisers had worried that Stevenson would not present the U.S. case forcefully. The two-time Democratic presidential candidate had after all counseled Kennedy to offer Moscow concessions rather than champion a muscular response. (He would be accused by unnamed administration officials in a story that ran in the Saturday Evening Post after the crisis concluded of having advocated a Caribbean Munich.) But Stevenson used his remarks to lambaste Soviet perfidy and call Cuba “an accomplice in the communist enterprise of world domination.” Kennedy was sufficiently pleased that he immediately dispatched a telegram to the ambassador: “I watched your speech this afternoon with great satisfaction. It has given our cause a great start.”

While U.S. diplomats were busy building international support for the U.S. position, Kennedy and his advisers continued to meet and review the situation. Pursuant to a directive that Kennedy had signed the day before formally establishing the ExCom, the group now met each day at 10:00 a.m. In the morning meeting CIA Director John McCone reported that intelligence suggested that the Cubans were bystanders on the missile installation rather than active participants. At the request of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Kennedy approved six low-level reconnaissance flights over Cuba to provide additional information about the Soviet missile sites. After seeing a photograph of Cuban aircraft lined up wingtip to wingtip, and thus highly vulnerable to a U.S. attack, Kennedy directed the U.S. Air Force to conduct a similar reconnaissance flight over U.S. air bases. Those photos confirmed what the president suspected: the U.S. Air Force had also failed to take prudent steps to disperse its military aircraft during the crisis.

In the late afternoon the White House received what it had been waiting for: a response from the Soviets. The Soviet Foreign Ministry gave the U.S. embassy in Moscow a letter from Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. U.S. ambassador Foy Kohler cabled the message to the State Department, which in turn delivered it to the White House. Khrushchev neither admitted to the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba nor offered any concessions. Instead, he pushed back, saying that the U.S. position “cannot be evaluated in any other way than as naked interference in domestic affairs of Cuban Republic, Soviet Union, and other states. Charter of United Nations and international norms do not give right to any state whatsoever to establish in international waters control of vessels bound for shores of Cuban Republic.”

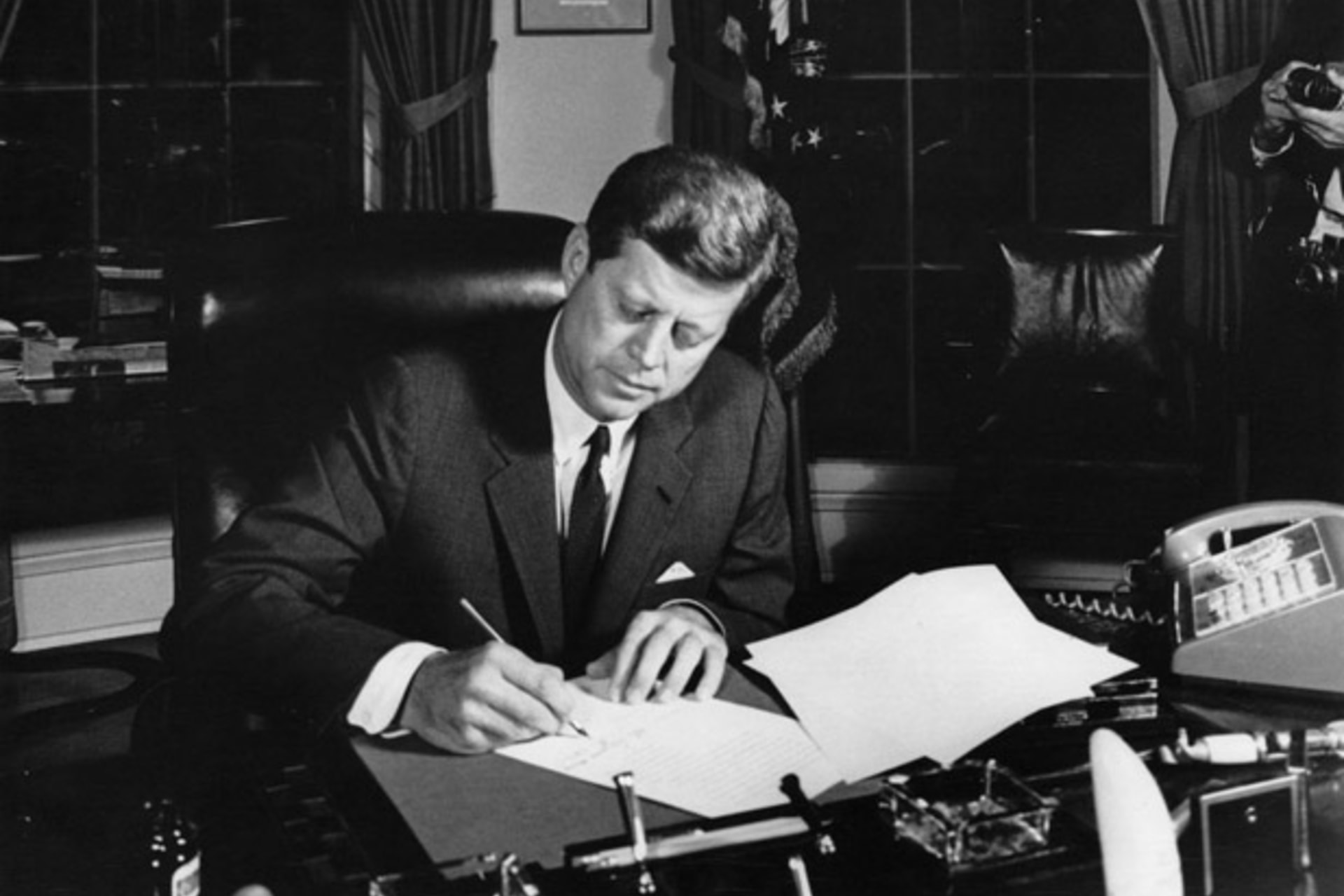

The ExCom reconvened at 6:00 p.m. Kennedy signed Proclamation 3504, which formally ordered the quarantine of Cuba to begin at 2:00 p.m. Greenwich time on October 24. Kennedy also agreed to answer Khrushchev’s letter with a letter of his own. It was blunt, telling the Soviet leader: “I hope that you will issue immediately the necessary instructions to your ships to observe the terms of the quarantine, the basis of which was established by the vote of the Organization of American States this afternoon.”

Later that night, Attorney General Robert Kennedy met secretly with Soviet ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin at the Soviet embassy in Washington. Acting at the president’s request, RFK hoped that Dobrynin might be able to provide insight into what Soviet leaders were thinking. Dobrynin insisted, however, there were no Soviet missiles in Cuba. (Unlike Soviet foreign minister Andrei Gromyko, Dobrynin was in the dark about Soviet plans for Cuba.) The attorney general left the Soviet embassy at 10:15 p.m. and headed back to the White House. He had little new to tell the president. The wait for a definitive Soviet response would continue.

For other posts in this series or more information on the Cuban missile crisis, click here.